Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Alpine Painting Matters

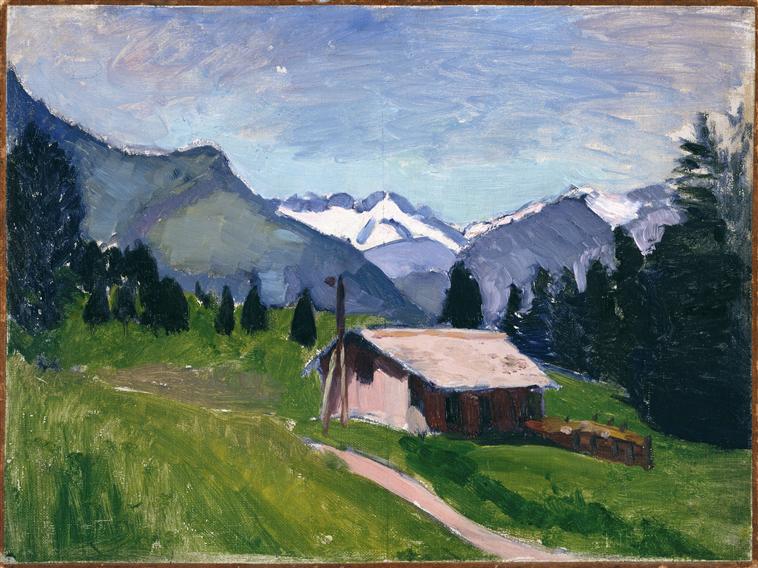

Henri Matisse painted “Savoy Alps” in 1901, a hinge year when the artist was shedding academic finish and discovering a modern grammar grounded in color, plane, and touch. Switzerland and the French Alps offered him clear structures—bands of meadow, rows of firs, layered ridges, a breathing sky—on which to test those ideas. The motif is humble and local: a small chalet perched on a green slope, a dirt path that curves toward its door, tapered conifers stepping across the mid-ground, and, beyond them, pale blue mountains capped with snow. Yet the way Matisse arranges and paints these elements turns the view into a disciplined experiment about how color relationships can build space and mood without theatrical shadow or topographical fuss. “Savoy Alps” is not a postcard of a named hamlet; it is a lucid construction of mountain air.

First Look: A Chalet Held Between Meadow And Peaks

The composition divides into legible belts. At the bottom, a bright green meadow tilts toward the viewer, cut by a pinkish path that winds to the chalet. The house sits slightly off center to the right—low, pale roof, darker ochre walls, a strip of reddish fencing—and is bracketed by stands of firs rendered as dark, tapered silhouettes. Behind them the world lifts through layered ridges of blue-violet toward snow-lit summits. The sky occupies a generous third of the picture, a cool expanse of light blue scumbled thin enough for the ground color to glow. Nothing in the scene is over-described; everything is named with a few tuned strokes so that the eye grasps the whole before it parses details. The result feels both calm and immediate, as if the air itself had been painted first and the land grew inside it.

Composition As Clear, Stable Geometry

Matisse designs the rectangle like a small stage set. The meadow forms a diagonal plane rising from lower left to mid-right. The chalet interrupts that plane, anchoring the slope and providing a place for the path to end. Vertical notes—the firs—punctuate the horizon and scale the distance. Beyond them the ridges stack in long, shallow triangles whose angles subtly vary, preventing monotony while preserving order. The tallest snow peak is kept low enough that the sky remains spacious; it is the air, not the Alpine drama, that governs the scene. The entire structure is a conversation between diagonals and horizontals: the path’s curve against the roof line, the tree spires against the long backs of mountains, the meadow’s thrust against the broad spread of sky. That balance stabilizes the painting and keeps attention moving.

Color Architecture And Early Matissean Harmony

“Savoy Alps” is built from a high, clear chord. The meadow’s greens are not monochrome; they shift from sap and olive into yellowed highlights near the path, then deepen toward the trees. The firs are near-black at their cores but breathe with cool greens and blue notes along their edges. The mountain range is a set of modulated blue-violets, some leaning toward cobalt, others toward slate, with the farthest forms paling into cool gray where the atmosphere thickens. Snow caps are not dead white; they hold lilac shadows and warm slips where light catches planes. The chalet is a warm interruption—a roof of thin creamy paint, walls of ochre and raw sienna—that makes the surrounding cools feel even cleaner. Throughout, Matisse avoids neutral gray; every mixture leans warmer or cooler so that relations stay tight and the image never dulls.

Light, Atmosphere, And The Breath Of The Sky

The light is even and pervasive, more like late morning than sunrise or twilight. There are no theatrical cast shadows; forms turn by temperature. The meadow brightens where the slope faces the imagined sun, and cools where grass falls away. The mountains model by gentle shifts from cool to cooler, gaining weight where ridges overlap and softening as they recede. The snow reads as luminous because the sky is laid thinly—its light seems to pour through the paint into the canvas and back out again, mingling with the milky impasto of the peaks. The effect is a breathable atmosphere rather than spotlight drama, truer to the sensation of standing high in clean air.

The Chalet And Path: Human Scale Without Anecdote

A small building and a narrow track are enough to declare human presence, but Matisse refuses anecdote. No windows are counted, no shingles described, no figures supplied. The house is a block of warm planes; the path is a pale ribbon that curves with the slope. Their function is structural: the path guides us into the picture, the chalet stabilizes the meadow and provides a warm center of gravity amid cool surroundings. That restraint preserves the serenity of the view and keeps the painting from becoming a story. The mood is contemplation, not incident.

Brushwork And The Register Of Materials

The surface records different “speeds” for different kinds of matter. In the sky, paint is brushed in smooth, lateral sweeps that show the bristle’s track and allow the ground to glow through—exactly right for a high, even vault of air. The mountains are built with angled drags and broader pulls, some strokes broken to suggest facets and ravines. Trees receive short, compact touches that taper upward; their darker paint sits slightly higher on the surface and catches real light. The meadow is a mix of longer horizontal strokes and small, directional dabs that angle with the terrain. Nothing is polished away; every area keeps a texture that suits what it describes.

Space Compressed Into A Readable Field

Depth is present and legible—the path comes forward, the firs are nearer than the ranges, the far peaks hover—but recession is intentionally modest. The meadow tilts like a thin carpet; the house sits with a slight naïve flattening; the mountains are stratified more than tunneled. That compression does not betray the scene; it reveals Matisse’s aim to maintain the painting as a designed surface first and an open window second. The world is built from bands and planes that interlock; the unity of the surface is never sacrificed for the illusion of miles.

Drawing Through Adjacency Rather Than Outline

Edges arise where color fields meet. The chalet’s roofline appears as a pale band sliding across darker trees; the firs are “drawn” by the collision of their dark bodies with the pale foothills; the mountain ridges read where blue-violet abuts sky or snow. When a line does occur—perhaps a thin dark stroke on the fence rail—it is broken, and its authority is quickly absorbed back into surrounding color. This economy keeps the entire surface integrated and gives the objects a soft, lived-in truth.

The Role Of Black And Near-Black

Matisse uses dark values sparingly and strategically. Inside the forest belt, near-black consolidates the forms, giving the middle ground weight. Under the chalet’s eaves and at the base of the fence, darker strokes compress energy and prevent the warm shapes from floating. Nowhere do these darks extinguish light; they act as active colors that intensify neighboring hues. This habit, already clear in 1901, will become a signature: black as a chromatic tool rather than a void.

Weather, Season, And Emotional Timbre

The palette suggests a clear, mild day in late spring or early summer. The meadow’s green is tender, not parched; the firs are saturated; the peaks retain snow. The emotional tone is steady and open. Many Alpine paintings chase sublimity through contrast and scale; this one proposes intimacy and poise. It is less about heights than about breath—the kind of view one sees from a hillside bench when the wind has died and the light is even.

The Savoy Motif As Laboratory

This subject allows Matisse to ask questions he needs answered. Can a small range of colors describe a wide world? How little drawing can secure the necessary edges? How much can space be compressed before the surface asserts itself and yet the scene remains convincing? The chalet, trees, and mountains are not just things seen; they are elements in an experiment that will underwrite the bolder color structures of the Fauvist summers at Collioure a few years later.

Dialogues With Impressionism And Post-Impressionism

The canvas inherits from Impressionism a commitment to present-tense light and outdoor work. From Cézanne it borrows the principle of constructing form through planes and strokes that follow the logic of a motif rather than the logic of a camera. There is also a Nabi taste for decorative clarity in the flat meadow plane and the patterned tree line. Yet the temperament is unmistakably Matisse’s: unlike Van Gogh, he calms agitation into harmony; unlike Gauguin, he avoids emblem and myth; unlike Cézanne, he relaxes tension into a gentle balance. The goal is a surface that reads quickly and rests the eye without becoming bland.

Materiality, Pigments, And The Skin Of Paint

The painting’s chord relies on pigments typical of 1901: cobalt and ultramarine blues for sky and mountain mixtures; viridian or emerald greens moderated with yellow for the meadow; earth ochres and siennas for the chalet; lead white thickened for the snow crests; small cadmium touches to warm edges. Matisse alternates thin scumbles (sky and some mountain planes) with slightly fatter, tacky strokes (firs and fence). The weave of the canvas remains visible in lighter areas, letting physical light mingle with painted light and contributing to the sensation of air.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path Through The Scene

The picture invites a particular route. The eye often enters along the pale path, pauses at the chalet’s warm planes, steps across the dark firs, climbs the short diagonals up the blue ridges, rests in the airy snow band, and finally glides into the sky before returning down the opposite slope to the meadow. That circuit repeats at a slower tempo as small correspondences insist themselves: a violet on a ridge echoed in a cloud shadow; a warm stroke at the fence answering a yellow-green in the grass, a cool seam along the roof rhyming with a pale streak in the sky. The landscape becomes not only a place but a rhythm.

Abbreviation And The Courage To Omit

Look at what has been left out. There is no rigorous description of shingles, no counting of needles, no narrative figures, no minute village in the distance. The omission is not poverty; it is clarity. By stripping the scene to essential bands and accents, Matisse lets the eye do the rest. The view gains freshness and legibility at the scale of a glance—exactly how landscape impressions live in memory.

How To Look Slowly And Profitably

Stand back and receive the large divisions of the chord: green ground, dark fir band, blue-violet ranges, luminous snow, and pale sky. Move closer to feel how edges are authored by adjacency rather than contour. Follow the path’s pink into the grass and notice how warm and cool strokes interleave to turn the slope. Study the mountain surfaces where a single diagonal drag can suggest an entire ridge. Step back again until the painting resolves into a single, breathable harmony. That oscillation between near and far mirrors Matisse’s working method—adjusting relations until the whole feels inevitable.

Relationship To Matisse’s Other 1901 Landscapes

Compared with “Green needles on the Cross Javernaz,” this painting is gentler in chroma and more anchored by architecture; compared with “Swiss Landscape,” it relies less on a sky-dominant composition and more on the interplay of meadow and chalet; compared with “Copper Beeches,” its palette cools and its geometry stretches into deeper space. Across all of them, the same principles hold: simplified shapes, decorative compression, temperature modeling, and a disciplined palette that builds clarity without noise.

Why “Savoy Alps” Endures

“Savoy Alps” endures because it turns a modest hillside into a complete lesson on how color, plane, and touch can make a world. It proves that a painting can be both decorative and true, that quiet can be modern, and that the simplest travel view—house, path, trees, mountains—can carry the authority of a carefully tuned chord. Long after the location is forgotten, the sensation remains: a chalet breathing under pale peaks, a path that invites you forward, and a sky that seems to hold the whole scene in a single draught of air.