Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Interior Matters

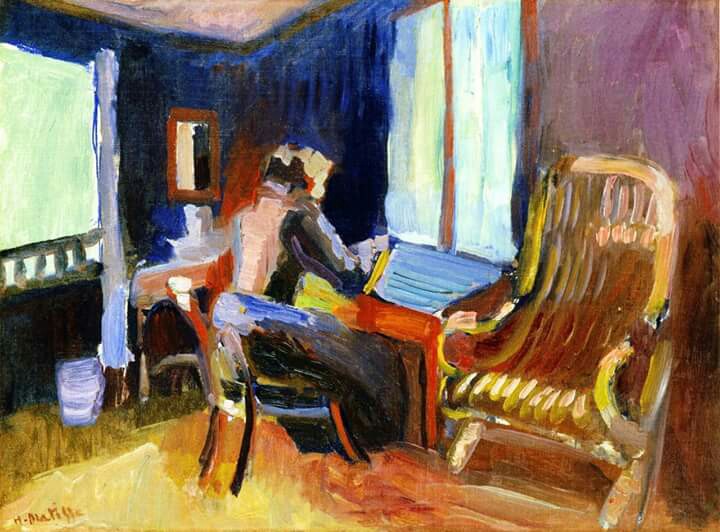

Painted in 1901, “Swiss Interior (Jane Matisse)” captures Henri Matisse at the moment he was moving from academic description toward the color-led construction that would soon blossom into Fauvism. After a rigorous schooling in Paris, he had been looking hard at Cézanne’s building of form through adjacent planes of color, at Gauguin’s simplifications, and at the Nabis’ decorative emphasis. The Swiss canvases from this year—landscapes, figures, and this intimate room—are laboratories where he tests those ideas not in theory but in lived space. An interior is a particularly revealing choice: it compresses architecture, furniture, light, and human presence into a single, orchestrated chord, forcing the painter to decide what truly carries meaning. In this picture Matisse declares that color relationships, not meticulous detailing, will carry the weight.

Subject And First Impressions

The scene is a private room. A woman—identified in many sources as Jane Matisse—sits at a writing desk near a bright window. A second, equally tall chair occupies the foreground at right, its wicker or carved slats catching the light. The left wall is dark, the ceiling pale, and a strip of cool window light slices down the center. The figure leans forward, absorbed; her body is a constellation of warm reds, violets, and dark blues; the desk glows orange; the floor is a polished amber that pools under chair legs and spills toward the threshold. From the first glance the room reads not as a set of objects but as a climate of color. Warm and cool, saturated and dulled, thin and thick—these oppositions establish mood before the mind has named a single piece of furniture.

Composition As A Theater Of Angles

Matisse engineers the rectangle with a handful of strong diagonals. The desk mass thrusts from right to left; the seated figure leans into it; the floorboards sweep forward; and the bright slab of the window drops like a vertical hinge into the middle of the scene. The right chair is set in a counter-diagonal, opening its arms to the viewer and stabilizing the push of forms toward the left. In the far corner, a small mirror punctuates the dark wall, a square against all that obliqueness. The composition reads like a stage: foreground chair as proscenium, window as light source and scrim, desk as central prop, writer as actor. Yet nothing is theatrical. The angles feel native to small rooms where furniture must fit and bodies find workable paths.

Color Architecture And The Prelude To Fauvism

The palette is high but controlled. A chord of nocturnal blues and violets wraps the walls, tempered by the cool, milky panes of the central window. Across this cool climate Matisse lays warm counterweights: the orange desk, the amber floor, the honeyed highlights of the wicker chair, and the salmon flashes in the sitter’s back and hair. A few acidic notes—yellow-green cushions, bits of citron on the chair’s ribs—add bite and prevent the harmony from slipping into languor. There is almost no inert gray; even neutrals lean warm or cool to maintain tension. Black is used sparingly as a living color (in the dress, under the desk, in the darkest chair slats), intensifying adjacent hues rather than extinguishing them. Everything is relational: a blue reads bluer beside the orange desk; a flesh note grows warmer beside the window; a brown becomes gold when struck against violet. This is Matisse’s early grammar of structure by color.

Light Without Theatrical Shadow

The room is lit by daylight, but Matisse refuses stagey contrasts. Instead of carving deep cast shadows, he lets light pervade the room, turning on and off as it meets different surfaces. The window gives a cool, almost chalky vertical that spills across the desk lid and sinks into the sitter’s shoulder. The floor brightens where it scoops up that light and darkens at the margins. The right chair gathers warm highlights along its ribs; the left corner lives in a blue dusk. The effect is more like a room remembered after a day than a room snatched in a blinding instant: illumination is even, legible, and atmospheric rather than theatrical.

The Brush As Evidence And Energy

Look closely and the surface displays a spectrum of touches chosen for material truth. The window is painted with smooth, vertical strokes that feel cool and planar—exactly right for glass. The desk and chair receive shorter, more ridged strokes, thickened to catch light like varnished wood. The sitter’s dress is laid in with flexible swaths of dark color that turn with the body; the flesh is warmed with small, direct notes rather than blended tones. The blue wall is a weave of long pulls and shorter crosshatches that keep it breathing; the ceiling is scumbled thin so the white ground contributes to the glow. Brushwork here is not decoration; it carries both texture and time, allowing you to sense the painter’s moves and the different “speeds” of each material—slow, glossy wood; soft, absorptive cloth; cool, slick glass; vibrating air.

Furniture As Actors

Matisse gives equal dignity to furniture and figure. The right-hand chair is not a prop; it is an actor with a voice. Its open arms and ribbed back are drawn in hot yellows, oranges, and amber-browns, translating tactile warmth and offering a visual welcome into the scene. Opposite, the desk is the picture’s warm anchor, set between cool wall and cool window like a hearth. The chair at the desk is darker, subordinate to the sitter’s body, and it disappears where it must so the figure can read. Each piece’s character is stated with a handful of decisive shapes and tuned temperatures. In a modern interior, the things you live with are companions; Matisse paints them as such.

The Figure: Presence Without Anecdote

The sitter’s identity is deliberately quieted. Features are suggested but not drawn; the face is a zone of warm and cool values rather than a portrait likeness. The posture says everything: a forward lean, an elbow anchored, a head bowed into work. The body is constructed through measured contrasts—cooler notes along the spine, warmer in the shoulders and arms—so that weight and volume read without classical modeling. This refusal to individualize heightens the mood of absorption. The viewer experiences not a narrative (“who is she writing to?”) but a state—concentration in a room tuned for it.

Space Compressed Into A Decorative Field

Although the room is convincing, depth is shallow and managed. The wall rises; the desk leans forward; the floor tilts; the big chair steps toward us; the window drops like a flat panel. Perspective is present but subordinated to surface harmony. By compressing space slightly, Matisse keeps your attention on the relationships that matter: how blue-violet walls make orange wood glow; how the window’s pale column divides and then reunites the room; how the foreground chair’s golden ribs rhyme with those in the floor. The painting remains true to the eye while asserting its identity as a flat, designed object—a key modernist move.

Drawing Through Abutment Rather Than Outline

The picture contains few hard contours. Instead, edges appear where one color abuts another. The sitter’s back is “drawn” where salmon-pink meets indigo-blue; the curve of the right chair’s arm is authored by the kiss of amber against plum; the desk lid’s bevel is stated where cool window light collides with warm wood. Where a line appears—along the chair’s leg, a stroke defining the desk’s corner—it is broken and absorbed into surrounding color. This method keeps the surface integrated and lets color do double duty as structure and illumination.

The Rhythm Of Looking

Matisse composes a loop for the viewer’s eye. Many enter through the golden chair at right—those emphatic ribs are hard to resist—then cross the orange desk to the cool window, sink along the sitter’s back into the dark left corner, and return through the warmer band of floorboards. The circuit repeats, slower each time, as small accents call out: a pale cup near the back wall, a blue note on the chair seat, a streak of green cushion under the sitter’s arm, a tiny mirror whose warm frame balances the desk. That rhythm is the room’s heartbeat—steady, calm, unhurried.

Silence, Sound, And The Psychology Of Interior Time

Paintings cannot speak, but they can suggest sound. This interior hums with quiet: pen on paper, chair creak, maybe a distant street. The dominance of cool blues and violets, broken by warm wood notes, produces the emotional timbre of concentration. It is a painting of refuge. The viewer feels admitted to a private slice of time and, by the restraint of the description, is asked to respect the quiet. That psychological tone is key to Matisse’s interiors across his career: they do not simply inventory objects; they choreograph a state of mind.

Dialogues With Predecessors

The canvas speaks to several traditions. From Dutch interiors Matisse inherits the dignity of domestic space and the play of window light on wood and fabric. From Manet he takes the courage to let large, flat areas stand as planes of value and color. From Cézanne he draws the principle of building forms with abutting patches rather than with contour and shadow. And from the Nabis he borrows the decorative flattening that allows a wall to be a saturated field. Yet none of these voices dominate. The temperament is distinctively Matisse’s: harmonizing, economical, intent on balance.

Materiality And The Skin Of The Surface

The picture achieves its unity partly through material moderation. Paint is not excessively thick; where Matisse needs luminosity he thins and scumbles so the white ground breathes through (window, ceiling, portions of the wall). Where he needs authority he lays body—edges of the desk, chair ribs, figure’s shoulder. Visible bristle marks are left as witnesses; they catch actual light and keep planes lively. The result is a surface that feels tuned rather than toiled, alive to small shifts but economically made.

What The Interior Reveals About Matisse’s Priorities

From this single room you can read durable principles that will govern Matisse’s art. Color organizes the world; drawing is achieved by adjacency; space must remain a designed fabric; omission clarifies; black functions as a color; and every element, from chair to figure to window, contributes to a single, stable chord. These choices are not doctrine—they arise from the need to make the room feel true. But they become doctrine through success: they work, and they will keep working as the painter moves into ever bolder keys.

Comparisons With Later Interiors

Place this 1901 canvas alongside the luminous interiors of 1908–1911 and you see both continuity and amplification. Later rooms explode with scarlet and arabesque pattern; contours harden into elegant linear whips; windows open to Mediterranean light. Yet the grammar is constant. The window remains a bright panel; furniture stays active; the figure is present by posture more than feature; surfaces read as fields; color carries structure. “Swiss Interior (Jane Matisse)” is a quiet blueprint for those later triumphs.

How To Look Closely And Profitably

Give the room time. Stand back and let the big chord register: cool walls and window, warm desk and floor, golden chair, dark figure. Then move in to watch edges form without lines. Track the temperatures across the sitter’s back and along the desk lid. Notice the small-cool to big-warm balance that keeps the composition steady: small cool mirror balancing big warm chair; cool window panel mediating between two warm masses. Step back again until the room reassembles itself in a single breath. The painting rewards that near/far oscillation because Matisse built it by the same rhythm, adjusting until each part found its role.

Why This Painting Endures

The canvas endures because it distills the experience of being inside: not the object-counting of a catalogue but the fused perception of space, light, and attention. It honors work—the ordinary work of writing at a desk—as a form of quiet grandeur. It proves that a room can be built from strokes and temperatures rather than architectural measurements, and still feel absolutely right. And it marks the moment when Matisse found a modern equilibrium: simplicity without thinness, color without chaos, decoration without forfeiting truth.