Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Moment And Why This Picture Matters

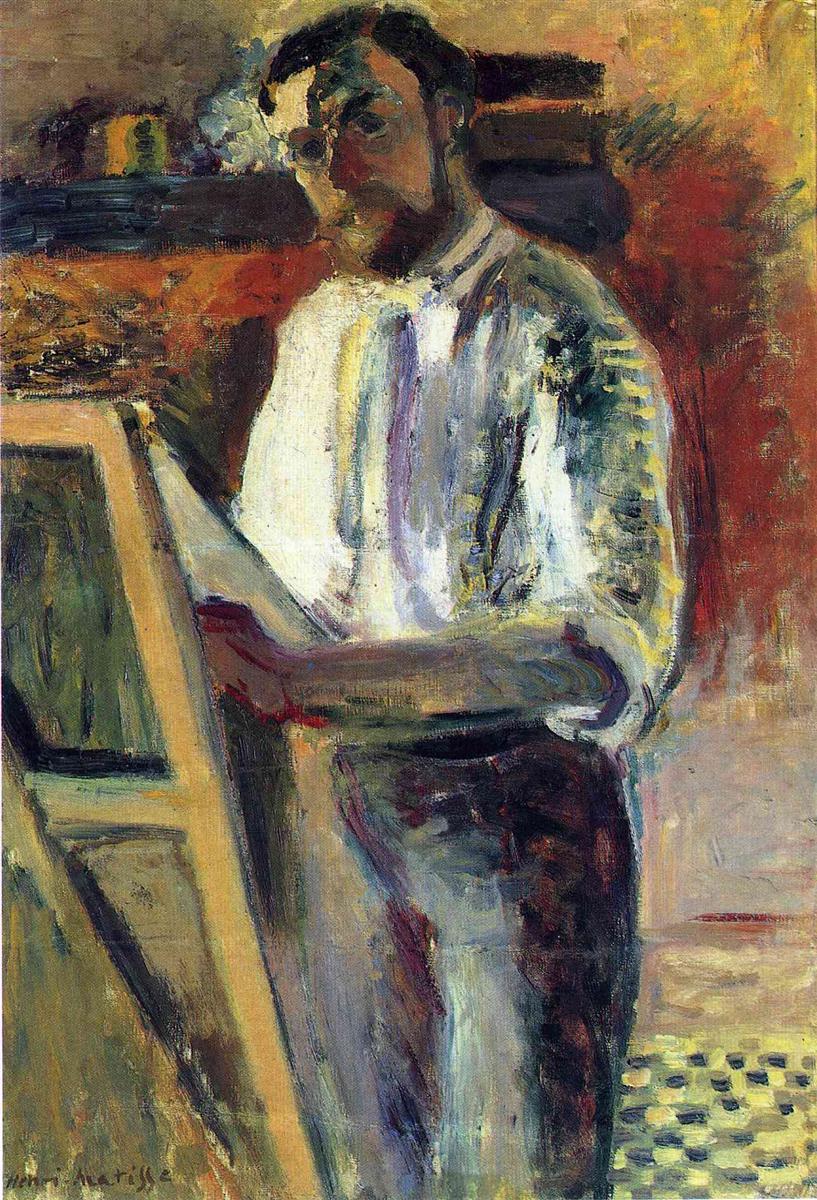

“Self-Portrait in Shirtsleeves” was painted in 1900, a hinge year when Henri Matisse was consolidating his break from academic finish and testing the language that would soon propel him toward Fauvism. He had mastered the École des Beaux-Arts regimen of contour, tonal modeling, and hierarchy, yet he was increasingly persuaded by Cézanne’s constructive color, Van Gogh’s charged brush, and the Nabis’ decorative flattening. This canvas sits right at that crossroads. It shows a young painter not in costume or ceremony but in working clothes before an easel, using his own face as a laboratory for decisions about color, plane, and the priority of the painted surface over strict description.

A Working Self: The Subject And Its Stakes

The subject is disarmingly simple: a half-length view of Matisse in shirtsleeves, without jacket, tie loosely suggested, sleeves rolled, standing at an easel with a canvas turned toward us. The decision to appear as a worker rather than a gentleman is programmatic. It places labor at the center of identity and allows the painting itself to serve as both portrait and statement of method. There is no theatrical prop; the easel is enough. The effect is matter-of-fact and modern, as if Matisse were saying that what defines him is not the trappings of studio life but the thinking done in front of a surface.

Composition, Cropping, And Vantage

The composition is a set of decisive diagonals. The left edge is dominated by the tall, angled rectangle of the canvas on the easel, which rises like a door into another space. Matisse’s torso pivots behind it, creating a zigzag from lower left to upper right, then back through the line of the shoulder and head. The head tilts, slightly enlarged by proximity, and crosses into the warm field of the back wall, which is streaked with oranges and ochers. The lower right opens into floor tiles and a paler zone that prevents the image from becoming top-heavy. Nothing is centered; everything is offset to generate a dynamic triangle among head, torso, and easel.

Drawing Through Planes Rather Than Outlines

One of the canvas’s important lessons is how little linear contour is required to make a figure cohere. The shirt is built from upright strokes of cool whites, lilacs, and blue-grays; the arm reads as an arm because warmer strokes gather toward the elbow and wrist while cooler notes push back toward the torso. The face is mapped as a set of planes—forehead, cheek, nose bridge—abutted rather than ringed. Where lines do appear, they are brief and functional: a dark notch at the collar, a crease at the elbow, a quick curve for the ear. The portrait is drawn by adjacency.

Color Architecture And The Emergence Of A Palette

Color is the architecture here. The warm wall steals across the upper right in oranges, rusts, and pale yellows. Against that heat Matisse places a river of cooled tones: the white shirt streaked with lilac and ice-blue, the greenish shadow along the easel, the slate and violet passages in the trousers. The head reconciles the two worlds—warm in beard and cheek, cool in the hollows around the eyes. Complementaries are deployed deliberately: red-brown beard against green notes in the coatless sleeve and background; yellow-ochre wall against violet-blue shirt; olive easel against purplish shadow. This is not local color recorded neutrally but a set of tuned relations that hold the figure and room in equilibrium.

Brushwork And The Record Of Looking

The handling is varied to assign weight. In the background Matisse uses broader, more horizontal sweeps, letting bristles rake the paint so the wall breathes. On the shirt the strokes are shorter and vertical, collecting into ribs that suggest fabric without rendering every fold. The face receives particular attention: compact, directional touches around the eyes and mouth locate expression; the beard is knit with quick, warm strokes that catch light but never stiffen. The easel’s frame is laid in thicker, almost carpentered strokes that give it gravity. Everywhere the surface remembers the tempo of a session in the mirror: deliberate, revising, but confident.

Light And The Replacement Of Modeling By Temperature

Illumination is diffuse, more like the even light of a working room than a staged spotlight. Instead of building form through dramatic cast shadows, Matisse modulates temperature to register depth. Cool notes carve the side of the nose, hollow the eye sockets, and cool the interior of the shirt; warm notes swell the cheek, lip, and parts of the wall. This strategy keeps the portrait coherent in low-contrast light and frees the painter to deploy color harmonies without being ruled by a single light source.

Space Compressed Into A Pictorial Field

Depth exists—the easel sits closer than the torso; the floor recedes; a shelf or ledge stretches behind the head—but space is shallow and stacked. The canvas-in-canvas at left is an angled slab that nearly coincides with the picture plane. Behind Matisse, the background is simplified into zones, not detailed furniture. The compression is purposeful: the image wants to be read as a constructed surface as much as a slice of a room. That double awareness, of painting and of place, is a signature move in Matisse’s early modernism.

Costume, Class, And Persona

By shedding the jacket and rolling his sleeves, Matisse signals an allegiance to the studio as workshop rather than salon. The shirt is not a symbol of informality alone; it becomes a major color field, a cool anchor that lets the hotter wall and the earthier trousers vibrate safely. The slightly loosened tie, sketched rather than polished, mediates between head and chest and introduces a thin vertical accent without fuss. Persona is thus constructed chromatically and compositionally, not as an anecdote.

The Easel As Counter-Self

The tall, leaning rectangle at left is more than prop. It is a counter-self: a second figure whose silent presence organizes the composition. Its cool greens and muted ochers oppose the warmth of the wall and beard; its structural straightness plays against the organic planes of the head and shirt. Because the working canvas faces away, it becomes an abstract panel—an emblem of painting rather than a picture within a picture. In that sense it is a manifesto: the mirror image of Matisse is inseparable from the task of painting itself.

Background As Theater Of Forces

The studio around the figure is translated into fields of energy. A belt of ochre and orange runs horizontally behind his head like a low horizon of heat; dark bands to the far left and upper right stabilize the rectangle; a patch of tiles in the lower right corner checks the flow of color with a little lattice of cool darks and creams. Nothing is incidental. Each zone is positioned to balance the picture and to make the head legible without recourse to outline.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The painting teaches the eye a route. You enter along the leaning easel, pivot into the cool column of the shirt, meet the mask of the face—dark eyes under a plane of forehead and a red-brown beard—and then slip into the warm band of the wall before descending through the darker trousers to the tiled corner. The circuit repeats, slower the second time, so the portrait can be reread as a balance of forces rather than a simple likeness. That rhythm mirrors the act of painting itself: approach, assess, adjust, return.

Affinities And Departures: From Chardin To Cézanne And The Nabis

Historically, artists often declared their vocation through self-portraits at the easel. Matisse adopts the motif but modernizes its language. From Chardin he borrows the respect for a working interior; from Manet, the courage to make large planes of paint read as objects; from Cézanne, the replacement of outline and perspective by constructive patches of color. The Nabis’ preference for decorative flattening resonates in the broad wall and the nearly emblematic easel. Yet the temperament is distinct. Matisse’s color is tuned for balance rather than drama, and his simplification aims for legibility rather than provocation.

The Face As Mask And Measure

Matisse gives his face the fewest strokes needed to convince. The eyes are shadowed ovals, not sparkling mirrors; the mouth is a short, dark line; the beard is a knitted plane of warm notes. The head functions as a measure for the whole: if the face remains legible at a distance, the balance of the picture is correct; if it dissolves, chroma or value needs adjustment elsewhere. The restraint in the features increases psychological believability. This is not a performance; it is concentration.

Materiality, Pigments, And The Tactile Surface

The palette signals the new century’s industrial pigments: cadmium and earths for the warm wall; cobalt and ultramarine cooling the shirt; viridian moderated into the easel’s gray-greens; lead white providing the body to knit strokes together. Paint ranges from thinly scrubbed passages—especially in the background—to richer deposits at structural edges and highlights. That variety of skin is not decorative excess; it encodes attention. Where Matisse needs certainty, the paint thickens; where he is content with a sensation, it thins and breathes.

Time Of Day And Atmosphere

The portrait offers no clock or window view, yet the subdued contrasts suggest an afternoon or indoor evening with steady, indirect light. The atmosphere is gentle rather than dramatic, and the room seems warm, as if heated by work and the glow of ochre walls. By forgoing strong, directional light, Matisse aligns the mood of the painting with the slow, recursive work of looking and adjusting in front of a canvas.

Omission As A Strategy For Clarity

Notice what is absent: no detailed studio clutter, no highly articulated hand, no gleaming spectacles, no explicit reflected image in the working canvas. Omission gives the image headroom. It allows each broad plane to play its structural role and prevents anecdotal elements from diluting the central chord of head–shirt–easel–wall. The painting insists that clarity is not achieved by accumulation but by selection.

Relation To The Other 1900 Self-Portraits

Compared with the darker, closer “Self-Portrait” of the same year, this picture pulls back to show the working body and the tool of the trade. It is lighter in palette, more open in composition, and more public in address. Together the two canvases form a diptych of identity: one image shows the inward face in heavy tones; this one shows the active, professional self in a field of color tuned for action. Both trust color to deliver character without the safety net of tight outline.

The Decorative Ideal Emerging From Work

Later statements about balance and serenity find early, practical embodiment here. The painting is not placid—the brushwork stays lively—but each area contributes to a stable whole. The long vertical of the shirt steadies the diagonals; the warm wall lingers like a chord behind the head; the cool greys of easel and floor keep the heat in check. The portrait reads as an interior harmony as much as a likeness.

How To Look Slowly

Stand back first and let the big chord register: warm upper right, cool vertical through the shirt, dark grounding below. Move in close to trace the route of the brush across the shirt and beard. Notice where edges harden—the easel’s outer frame, the contour of the forearm—and where they dissolve—the far shoulder, the side of the head into the warm wall. Return to the eyes; see how little is said and how much is implied. Then step back again until everything locks into a single balance. That alternation between near and far echoes the painter’s own working rhythm and reveals why the surface feels both candid and composed.

Why This Painting Matters

“Self-Portrait in Shirtsleeves” matters because it makes a modern claim for what a portrait can be. It shows that identity may be more truthfully conveyed by the harmonies that surround a face—the colors of a room, the weight of an easel, the temperature of a shirt—than by meticulous transcription of features. It declares that work is part of character and that painting’s first responsibility is to its own surface. Within five years Matisse will heighten chroma and streamline form, but the logic—color as structure, omission as clarity, decoration as truth—stands here, quiet and persuasive, in rolled-up sleeves.