Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Moment It Captures

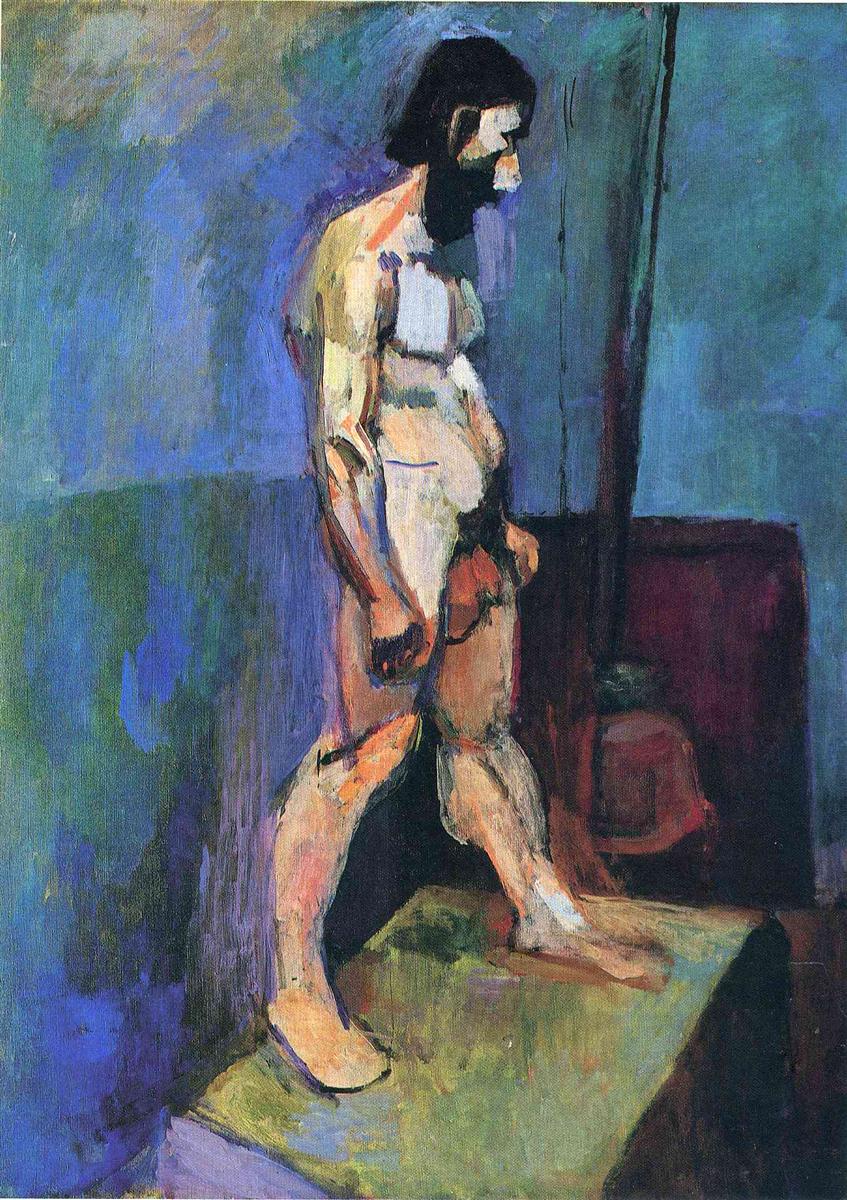

“Male Model” (1900) belongs to the intense transitional years when Henri Matisse was loosening the grip of academic training and testing a new grammar of color, structure, and simplification. He had studied in Paris under Gustave Moreau and at the École des Beaux-Arts, learning the studio disciplines of drawing from plaster casts and nude models. Around 1900 he was also absorbing the structural color of Cézanne, the expressive charge of Van Gogh, and the decorative flattening championed by the Nabis. This painting records that crossroads. It is not yet the radiant Fauvism of 1905, but its decisions—tilted planes, sculptural color, abbreviated drawing—announce the direction of his modernism.

The Academic Nude Reimagined

The male nude was a core exercise in the schools: a test of anatomy, proportion, and the ability to model volume through light and shade. Matisse honors the task while reinventing its means. The model stands in three-quarter profile on a platform, feet planted and fists loosely clenched, the beard and compact torso giving him a monumental, almost archaic presence. What departs from tradition is everything around and within that figure: the background is a quilt of greens, blues, and purples rather than a neutral studio gray; contours are built by wedges of color as much as by line; and passages deliberately resist finish, allowing the painter’s choices to remain visible.

Composition, Vantage, And The Stage Of The Platform

The figure is placed high and left, creating an asymmetry that energizes the rectangle. The platform thrusts diagonally into the foreground, a tilted stage that lifts the model toward us. Behind him, vertical and horizontal divisions of color suggest a wall seam, a post, and perhaps a draped fabric, yet these elements are simplified into planes that read more like architecture of paint than a literal room. The empty expanse to the left is not wasted space; it gives the body room to breathe, emphasizes the forward tilt of the pose, and sets up a counterweight to the dense, darker right half. The composition encourages the eye to travel in a loop: along the platform, up the front leg, through the torso to the beard, and back out into the field of color.

Anatomy Built With Planes

Rather than wrapping the body in meticulous chiaroscuro, Matisse constructs volume with interlocking planes of warm and cool. Shoulders and flanks are mapped by slabs of ochre, salmon, and violet; the abdomen is a pale panel edged by blue-black accents; the shins and feet are simplified into large, light masses whose contours are found and lost. The marks have the decisiveness of sculptor’s cuts. Even small features—knuckles, collarbone, knee—are suggested with economical touches, enough for the structure to read without collapsing into academic detail. The result is paradoxical: the figure looks both generalized and specific, a type built from sensations of light and pressure.

Color As Structure And Temperature

Color is the true engine of this painting. The flesh is not a single tone but a chord—peach, ivory, yellow-green, lavender, and traces of red—set against a cool environment of turquoises, blue-greens, and violets. These complements make the body advance optically while the room recedes. Instead of casting cast shadows, Matisse modulates temperature: cool blues carve the underside of arms and the hollow of the back; warmer notes swell the calves and chest. Black, used sparingly in contour and beard, is never a dead boundary; it vibrates against neighboring hues and clarifies the figure’s silhouette. The painting holds together because these colors lock like masonry, each note chosen for its relation to the whole.

Brushwork And The Record Of Looking

The surface is alive with varied touch. In the background, long vertical strokes knit the wall into a breathing field, while the platform is dragged horizontally, compressing space and differentiating materials. On the body, shorter, shaped strokes articulate form: a vertical pull to establish the thigh, a hooked stroke to indicate the deltoid, a scumbled patch to round the hip. Edges harden and soften strategically—firm at the leading shin and forearm, blurred at the far shoulder and heel—guiding the viewer’s focus and suggesting motion within stillness. The handling retains the time of its making; you can feel the painter testing, adjusting, and learning from each stroke.

Light And Atmosphere Without Spotlight Drama

There is no theatrical beam sculpting the model. Illumination seems soft and omnidirectional, the kind of ambient studio light that suppresses hard cast shadows. Matisse uses this neutrality to his advantage: with shadow minimized, color relationships can carry the description of form. The atmosphere is created by the cool field that wraps around the figure, a veil of blue and violet that both pushes him forward and carries the psychological temperature of the room—calm, concentrated, unadorned. The absence of strong highlights keeps the body matte and monumental, closer to stone than to polished skin.

Space Compressed Into A Pictorial Field

The platform gives classical depth cues, yet space is ultimately shallow. Background planes meet the figure like puzzle pieces, and the floor leaps quickly to the base where the feet stand. The vertical element at right, which might be a pole or structural post, flattens into a dark band; the reddish rectangle behind the calf reads as both a wall and a color counterweight. This deliberate compression is crucial: the nude is not displayed in an illusionistic box but set inside a designed field where every patch participates in harmony. Matisse is already privileging the truth of the canvas plane over theatrical recession.

The Studio Made Abstract

Hints of the studio—platform edge, wall seam, prop—remain, but they have been simplified to the point of symbolism. The room has become an abstract instrument, tuned to make the body resonate. The green-blue ground cools the whole; the maroon patch warms and stabilizes the right side; the vertical dark bar adds structure. By refusing to describe the studio in detail, Matisse avoids anecdote and keeps attention on the essential relation between figure and field.

Dialogue With The Tradition Of The Male Nude

From Renaissance academies to nineteenth-century ateliers, the male nude was the standard by which mastery was judged. Matisse engages that tradition while shifting its values. Where earlier artists chased ideal proportion and polished finish, he seeks a living structure built from immediate sensation. The bearded head and compact torso echo classical vigor, yet the lack of heroic narrative returns the focus to the act of seeing. The figure is neither mythologized nor eroticized; he is a subject for painting, stripped of everything but weight, balance, and the energy of color.

Affinities With Cézanne, Gauguin, And Van Gogh

You can hear Cézanne in the construction of the body by angled planes and in the refusal to let perspective dominate the composition. Gauguin murmurs in the simplified silhouettes and the reliance on large, unbroken areas of color to carry mood. Van Gogh appears in the charged brushwork of the background, the sense that space is a field of strokes rather than empty air. Yet the temperament is Matisse’s: steadier, more measured, committed to decorative balance. The painting does not storm; it gathers.

The Psychology Of Presence

Although the model’s face is turned away, the painting conveys a distinct psychological presence. The clenched fists, slightly forward lean, and set jaw imply endurance. He is waiting, holding a pose, perhaps in the cool of a morning studio. The monumentalization of an ordinary body carries an ethical charge: dignity belongs to the model not because of narrative or myth but because of how the painting organizes attention around him. The viewer is invited to meet the figure at the level of form and sympathy rather than story.

Materiality, Pigments, And The Skin Of Paint

The color range suggests the expanded industrial palette available by 1900: cobalt and ultramarine for blues, viridian for green notes, earth pigments for ochres and umbers, and lead white to modulate flesh. Matisse alternates thin scumbles—especially in the background, where underlayers flicker through—with thicker, more saturated passages in the body. This layering creates optical depth without resorting to academic glazing and keeps the surface animated. The paint’s very substance registers as meaning: solidity gathers where paint is richer; air thins where it is brushed lightly.

Rhythm And The Viewer’s Path

The composition leads the eye like a melody. The platform’s diagonal acts as an opening phrase; the bright wedge at the toe hooks attention and sends it up the shin; the abdomen’s pale panel is a sustained note; the beard and head are a quick accent; the long descent along the back leg resolves the phrase. Background color shifts—cool to warm, dark to light—keep the eye circulating so the figure never becomes a static statue. This rhythmic organization is the visual analogue of the model’s held breath and steady balance.

Abbreviation And The Courage To Omit

Where academic conventions would demand a full accounting of fingers, tendons, and facial features, Matisse declines. He knows what to leave out. The right hand is a compact block with just enough articulation to read; the face is a set of planes with a wedge for a nose and a mass for the beard; the toes are schematic. These choices grant speed and authority to the picture. Omission is not a failure to see but a strategy to keep the whole alive.

The Decorative Ideal Emerging

Even at this early date Matisse is moving toward an art of integrated surface harmony. Each zone of the canvas contributes to balance: the maroon patch steadies the cool sea of blue-green; the vertical bar tunes the rhythm of horizontals; the platform’s olive complements the pinks of the flesh. The nude is no longer an isolated subject dropped into a background; he is one voice in a chord. This decorative ideal will later flower in interiors and odalisques, but its seed is clearly planted here.

Comparisons With Later Figures

Set this painting beside the purer Fauve works of 1905–1906 and you see continuity beneath change. Later figures will be brighter, outlines more assertive, backgrounds flatter, yet the fundamental approach—planes of color constructing form, space compressed to serve harmony, abstraction bracketed by empathy—remains. “Male Model” is the disciplined rehearsal before the performance, evidence that Matisse’s radical color would grow out of drawing rather than replace it.

How To Look Closely

Begin with the largest oppositions: warm body against cool room, dense right half against airy left. Let your eye travel the diagonal of the platform and feel the pull of gravity as the figure leans. Notice where edges are crisp and where they blur, and how that shift affects your sense of material and distance. Attend to the places where distinct hues meet—a purple edge against a pale thigh, a greenish shadow against the foot—and sense how those meetings substitute for outlines. Step closer to read the variety of touch; step back to let the composition reassert its calm. In alternating near and far, you experience the painting as Matisse made it: a negotiation between parts and whole.

Why This Painting Matters

“Male Model” matters because it demonstrates, in a pared-back studio exercise, the core of Matisse’s project. It shows that color can carry structure, that simplification can deepen presence, and that the surface of a painting can be both decorative and truthful. By reimagining the academic nude as a constructed harmony of planes and temperatures, Matisse opens a path away from imitation and toward invention grounded in observation. The painting respects the model, the room, and the tradition, yet it claims new freedoms that will define twentieth-century art.

Legacy Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas occupies a quiet but crucial place in Matisse’s oeuvre. It ties his disciplined beginnings to his audacious future, and it reveals the method that will sustain him for decades: choose a stable motif, simplify it to essential planes, tune the color until the whole sings, and let the viewer complete the scene. In later decades, whether painting odalisques in patterned rooms or cutting paper into radiant figures, he will still be working from the grammar tested here. The male model of 1900 is thus more than a student exercise; he is an early emblem of Matisse’s faith that painting can remake the world through color and balance.