Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And The Moment It Captures

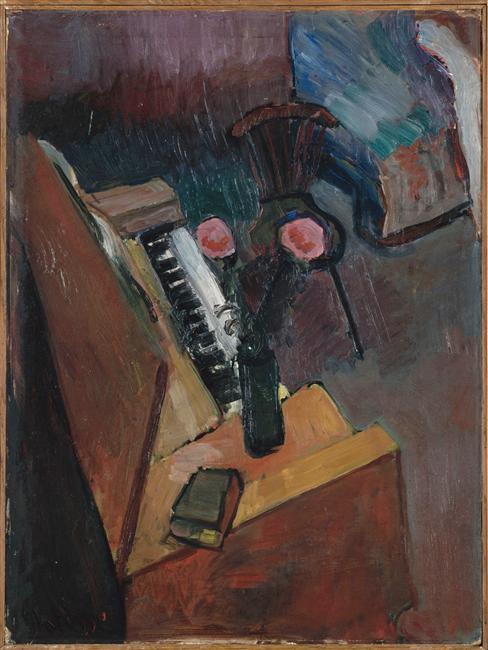

“Interior With Harmonium” was painted in 1900, when Henri Matisse was negotiating a decisive turn from academic training toward the chromatic freedom and structural clarity that would soon ignite his Fauvist breakthrough. He had absorbed Cézanne’s constructive approach to color, looked closely at the decorative flatness of the Nabis, and was testing how far he could compress space without losing the felt reality of a room. This painting is a laboratory for those questions. It is not a grand salon scene or a narrative tableau. It is an ordinary corner, thick with paint and decisions, where furniture, flowers, and a modest keyboard instrument become building blocks for a new pictorial language.

The Subject: A Harmonium As The Heartbeat Of A Room

The harmonium—a small reed organ common in bourgeois interiors at the turn of the century—anchors the composition like a domestic altar. Its keys form a ladder of light within an otherwise dusk-toned field. Unlike a concert piano that boasts polish and prestige, the harmonium is intimate and utilitarian, meant for the private pleasure of music. By centering this instrument, Matisse turns the room into a chamber of listening and suggests a mood of pause rather than performance. The instrument’s presence also licenses the painting’s audible rhythm: diagonals move like scales, dark and light alternate like measures, and the entire surface breathes with a slow tempo appropriate to a solitary evening indoors.

An Audacious Vantage: Looking Down Into Space

The first sensation on seeing the picture is the steep tilt. Matisse positions us above the scene, as if standing on a chair and leaning over, so that the objects fan outward from the lower left corner. The harmonium’s keyboard slides away at an angle; a bottle-vase bearing two pink flowers rises like a metronome at center; a chair flares its spindles near the top; and a bulky, upholstered object in cool blues and creams occupies the right. This plunging view generates tension between recession and flatness. The plane on which everything rests presses up against the picture surface, yet the diagonals tug our gaze inward. The room becomes a shallow, tilted stage where forms approach the eye and then retreat, the way chords advance and dissolve when played softly.

The Composition’s Spine: A Diagonal Architecture

A firm diagonal runs from the lower left to the upper right, traced by the edge of the harmonium and the long slab of the desk or table that crowds the foreground. This line is answered by a counter-diagonal formed by the shadowed floor and the slope of the chair’s legs. Between them a triangle of light opens around the vase and blossoms. These interlocking vectors choreograph the viewer’s path: we enter along the instrument, pivot around the vase, and drift toward the chair and the blue object at right before looping back. The geometry is simple, almost abstract, yet it holds a roomful of specific things.

Color As Structure: A Chord Of Earth And Night

The palette is a deep chord of auburns, umbers, violets, and near-blacks relieved by punctual notes: the pale pink of the flowers, the chalky staircase of keys, and the cool pool of blue on the right. Matisse refuses a naturalistic light that would model every object; instead, he builds the space by balancing temperature and value. Warm browns thicken the foreground and left flank, cool greens and blues hollow the middle distance, and the highest value passages—the blossoms and keys—glint like percussion. Black is not absence here; it is an active color, consolidating shadows and intensifying adjacent hues, especially the rose heads and the slim neck of the bottle. The harmony is grave but not dour, akin to a minor key whose beauty resides in its restraint.

The Brush As Weather And Time

Paint is applied in a range of speeds. In the floor and walls, broad strokes slide diagonally, their bristles leaving visible tracks that suggest brushed velvet or wood grain. On the harmonium and the tabletop the paint grows denser, scraped and dragged to catch edges of light. The flowers are slapped on in concise circular strokes that feel immediate and alive. This orchestration of touch allows Matisse to distribute attention without overdescribing. One senses the painter moving around the easel, accelerating and pausing, revisiting passages as the composition settles into balance. The surface remembers that time, and the viewer reads it as atmosphere.

Light Without Theatrical Illumination

The room has no singular light source. Instead, illumination is an even, subdued wash that thickens or thins depending on the materials it touches. The keys catch the most light because they are white; the bottle shines at its shoulder because glass naturally gathers a highlight; the blue upholstery reads cool because its pigment contains more white and blue. Shadows are colored zones rather than transparent pools: bruised violets around the chair, wine-dark browns along the harmonium’s case. The result is a diffusion that suits the mood of private music and quiet thought, and it allows color, not spotlit drama, to shape perception.

Space As A Negotiation Between Depth And Surface

The tilted perspective compresses the room into a stack of planes. The harmonium and desk are foreshortened so aggressively that they almost become slabs of color, while the chair lifts toward us like a silhouette. The large brown wedge in the lower left has very little detail; it is simply mass. Yet the keyboard, with its alternating lights and darks, insists on recession, and the floor’s brushstrokes run counter to the instrument’s lines, creating a shallow scissor of depth. This oscillation is not a technical defect; it is the picture’s modern power. Matisse allows us to shuttle between reading objects in space and contemplating shapes on a flat surface, making the act of seeing itself part of the subject.

Objects As Actors: Vase, Chair, Book, And Blue Upholstery

Each item plays a defined role in the drama. The bottle-vase is the vertical keystone. Dark and narrow, it punctures the diagonal sweep and supports the two roses, which serve as small suns in a dim climate. The chair is a fan-shaped echo—its spindles radiate like ribs, softening the room’s hard vectors. The small closed book on the desk is a block of thinking; its greenish cover cools the warm tabletop and suggests another quiet practice beside music: reading. Finally, the upholstered mass at right, touched with streaks of blue, cream, and russet, is both furniture and color field. It redistributes weight to the picture’s right flank and sets a cool counterpoint to the warm harmonium. In a room without figures, these objects serve as stand-ins for human activity and the habits of an interior life.

Negative Space And The Courage To Leave Things Out

A large portion of the canvas is given to areas that do not name themselves—patches of floor and wall in which color and directionality do the talking. This is a strategic omission. By not itemizing every edge or molding, Matisse lets the significant relationships ring louder. The keyboard reads because the surrounding areas are spare; the roses glow because the ground behind them is a veiled dusk. Leaving things out becomes a form of clarity, a way to make the room intelligible as an arrangement of forces rather than a catalog of objects.

Rhythm And The Music Of Seeing

The painting invites a musical kind of looking. Repetition and variation guide the eye like melody and harmony. The alternating white and black keys are an obvious rhythmic pattern; their echo appears in the fence-like slats of the chair. The two pink blooms rhyme with one another, and their circular forms answer the elliptical tops of the bottle and the book. Diagonal sweeps in the floor repeat at different tempos, sometimes long and calm, sometimes short and quick. The whole interior feels scored rather than mapped, and the viewer, following these cues, reads the room as a sequence in time.

Relationship To Earlier And Later Matisse Interiors

Compared to the effulgent interiors of 1908–1911, with their saturated reds and lush arabesques, this 1900 room is somber and tight. Yet the family connection is unmistakable. The tilted plane anticipates the rising tabletops in later still lifes. The use of a strong, central vertical as an organizing axis prefigures the thrust of vases, windows, and figures that will structure later compositions. The insistence that black is an active color, not a negation, will persist throughout his work. Most importantly, the aim for decorative harmony is already present: every part of the room is bent toward equilibrium, where nothing is so descriptive that it breaks the chord.

Dialogues With Cézanne, The Nabis, And The Symbolists

Cézanne’s lessons are visible in the way planes are built with patches of color rather than with linear perspective. The harmonium’s case is not “drawn” so much as assembled from leaning facets of brown and green, each parcel of paint holding its own while contributing to a larger tectonics. The Nabis’ influence shows in the willingness to let furniture and floor flatten into patterned fields, as if the room were a tapestry. There is also a whisper of Symbolist interiority: the muted palette, the elevation of a musical instrument, and the absence of figures give the scene a reflective, almost spiritual undertone without resorting to explicit allegory.

Materiality: Pigments, Surface, And The Hand

The surface is complex. Thin, scumbled passages let underlayers breathe in the floor and walls, while thicker, more saturated paint defines the instrument and tabletop. These shifts are not arbitrary; they stage a hierarchy of attention. One suspects the use of earth pigments moderated by touches of cobalt and viridian to cool the shadows, and a reserve of lead white to strike the keys and blossoms. Whatever the precise chemistry, the material effect is palpable. You feel drag where the brush works against resistance, glide where it skates across a smoother layer, and a rasp where a drier stroke catches on the tooth of the canvas. That physicality is a reminder that the room exists in paint before it exists as a picture of a room.

The Psychology Of Domestic Space

Because no human figure appears, the viewer is invited to occupy the position of the absent inhabitant. The closed book, the quiet instrument, and the unfurling roses create a mood of intermission—the interval between reading and playing, between action and contemplation. The darkness is not threatening; it is intimate. The angle from above further enhances this psychological tone. We are not seated politely at a distance; we hover, as someone does when lost in thought, noticing the tilt of things and the way light glances off a bottle’s shoulder. The painting becomes a portrait of a state of mind rather than a picture of furniture.

The Decorative Ideal Emerging From Observation

Matisse’s later statements about seeking balance and serenity find early visual form here. The room is observed from life, but observation is continually subordinated to decorative unity. Colors are tuned to one another rather than to local appearances; shapes are simplified until they act like components of a pattern; brushstrokes keep the surface lively without dissolving into chaos. The harmonium and flowers, though humbly rendered, carry symbolic weight as stabilizing motifs in an ornamental syntax. This is how Matisse reconciles the real and the ideal: he lets the real generate the motif and the ideal govern its arrangement.

How To Enter The Painting Through Looking

Begin by letting the diagonal from lower left to upper right register as a physical pull, like gravity. Notice the triangular clearing around the vase, a clearing created by three planes—the desk, the harmonium’s top, and the darker floor. Let your eye climb the bottle to the two small suns of paint that are the blossoms, then drift to the cool block of blue at right and the fan of the chair’s back. Return to the keys; feel how their pattern accelerates your gaze and how the rest of the room slows it down. Attend to where edges harden and where they dissolve, and to how those choices tell you when Matisse wants form to insist or to yield. In a few minutes of such looking the room discloses its dual nature: a place you could sit in and a tapestry of colored forces.

Why The Painting Still Matters

“Interior With Harmonium” matters because it demonstrates, in an early key, how modern painting could be both faithful and free—faithful to the weight and use of everyday things, free in the ordering of color and space. It shows Matisse learning to let the surface carry meaning and to rely on the viewer’s perceptual intelligence to complete the scene. It honors domestic life without anecdote and proposes that beauty can arise from the simplest of means: a diagonal, a chord of browns and blues, two roses lifted on a black stem of glass. In its quiet way, the painting clears a path for the more audacious interiors to come and, beyond them, for the flat, radiant harmonies of the cut-outs.

Legacy Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Placed alongside the landscapes and still lifes of 1900, this interior reveals a consistent project: to convert observation into a stable pattern of forces. Over the next five years Matisse will amplify color, relax drawing, and simplify form, but the grammar debuted here remains intact. The harmonium’s keys become prototypes for stripings, grids, and checks that will animate later rooms; the hovering vantage reappears whenever he wants to tip a table into the field of vision; the dialogue between black and saturated color will become one of his signature harmonies. The painting is thus both a document of a specific evening and a cornerstone in the architecture of his art.