Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Place In Matisse’s Early Career

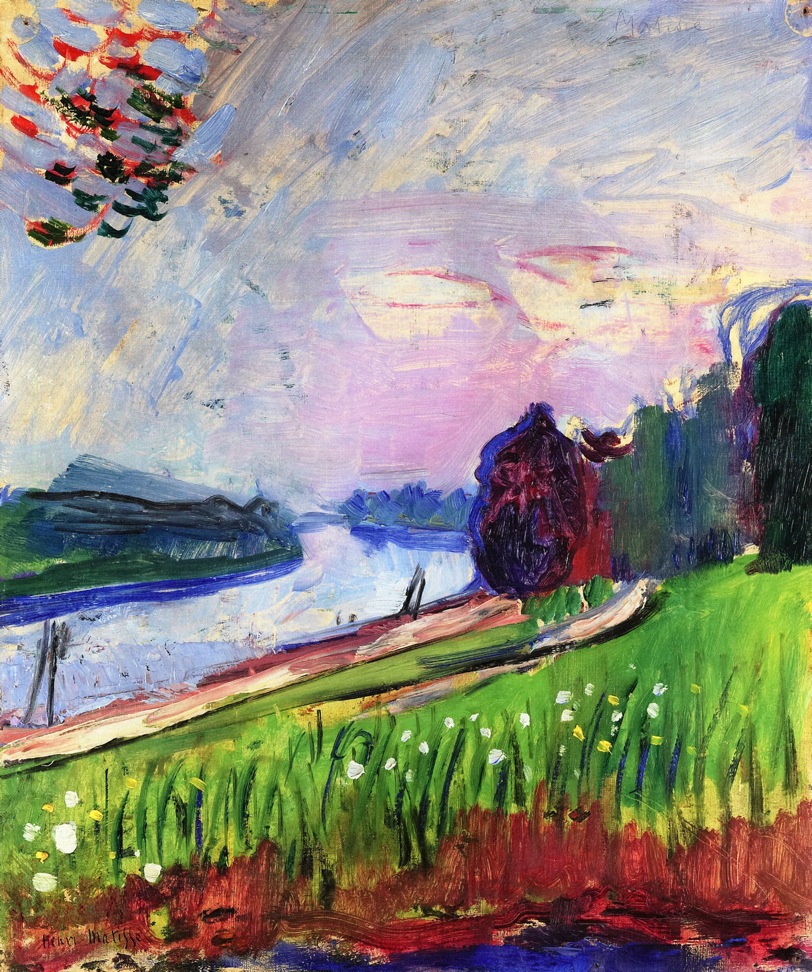

“Copse of the Banks of the Garonne” dates from 1900, a decisive year when Henri Matisse was reconciling the lessons of academic training with the chromatic freedom he had absorbed from Impressionism and the more radical experiments of Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Cézanne. He had already painted in Belle-Île and in the south, he had studied how Cézanne built forms with color, and he was gradually shedding the careful tonal modeling inherited from the École des Beaux-Arts. This landscape captures that pivot. It shows an artist still attentive to observed nature yet willing to let color, gesture, and simplification speak louder than finish. Before the explosive breakthroughs of Collioure in 1905, Matisse rehearsed his revolution on riverbanks like this one, using provincial motifs to test an emerging language of intensity.

The Garonne As Motif And Geography

The Garonne, coursing through southwest France and eventually merging into the Gironde estuary, offers an elastic subject: broad reaches of water, low horizons, and stacked strips of bank, field, and sky. In this canvas the river is not a postcard view framed symmetrically; it is a living artery that turns, narrows, and disappears. The title emphasizes the “copse,” the small congregation of trees at the right edge that anchors the bank. The river reads as movement and time; the copse reads as pause and stability. Matisse is not cataloguing local flora so much as setting up a conversation between flow and rootedness, between a ribbon of blue that implies travel and a dark, weighty mass that insists on here and now.

Composition And Vantage: Diagonals, Horizon, And Flow

The composition pivots on the long diagonal of the near bank that slices from lower right toward the center. That line, buttered with ochers and greens, acts like a ramp pulling the eye into space. A second diagonal, the river’s far edge, runs counter to it, creating a shallow V that funnels attention toward the distant bend. The horizon is low, giving the sky more than half the canvas; this produces a sensation of openness and breath. The copse, pressed to the right margin, is not placed as a central monument but as a counterweight. Its vertical thrust opposes the lateral sweep of land and water. The left upper corner contains a burst of foliage that seems to hang into the scene like a stage prop, a reminder that we view the river through a fringe of leaves. Altogether, the scene is organized less by linear perspective than by a choreography of vectors that keeps the eye in circulation.

Color Architecture And The Early Language Of Fauvism

The first shock of the painting is its color. The sky is a cold, milky blue streaked with lavender, and at the horizon it flares into a pink and violet bloom that feels more emotional than meteorological. The grass at the right swells in a high, saturated green that not only asserts spring but also creates a chromatic engine for the entire picture. A belt of red-brown earth along the bottom smolders against that green, establishing a classic complementary clash that makes both hues vibrate. The copse is rendered in blackberry purples and wine tones, punctuated by emerald highlights that refuse literal description yet ring true as notes in a color chord. Matisse is already using color structurally—green to erect planes, purple to compress them, pink to infuse air—so that the scene holds together because the colors interlock rather than because each object is faithfully shaded.

Brushwork, Texture, And The Physicality Of Weather

The paint handling is urgent, exploratory, and varied. In the sky Matisse skates the brush flat, letting bristles leave parallel tracks that feel like high wind. In the river the strokes lengthen into horizontal pulls, granting the water a silvery skin. On the bank the gestures thicken; pigment is dragged in short, rising marks that mimic blades of grass. The copse is built from piled daubs and short arcs that mass into a single weighty form. This textural modulation does two things at once: it indexes the materiality of the world—soft air, slick water, fibrous vegetation—and it keeps the surface alive as a record of the painter’s motions. The world is translated into weathered paint, and the weather is felt in the body of the brush.

Light, Atmosphere, And Time Of Day

The picture suggests a late afternoon or early evening when the sky cools and the last warmth lingers low. Instead of modeling the bank with shadow Matisse lets temperature do the work: cool violets bathe the distance while warm greens and reds insist upon the foreground. The central flare of violet-pink at the horizon acts like a lamp behind gauze, washing the river with reflected light. What matters most is not a naturalistic account of sunlight but the sensation of air—transparent, mobile, and saturated with color. The painting is an atmosphere you could step into, a zone where light is less a source and more a medium.

Drawing, Line, And The Courage To Omit

Matisse’s drawing is selective and declarative. A few dark calligraphic strokes articulate the edge of the path and the river; a handful of thin uprights stand in for posts. The flowers scattered in the grass are white buttons—mere circular touches—yet they secure the scale and season. Details that academic convention would demand, such as individual leaves or ripples, are omitted. The omissions are not gaps; they are decisions that keep the eye moving and reserve energy for the essentials: trajectory, temperature, and rhythm. In place of outlines, Matisse often lets one color butt against another—the green bank against the red soil—to produce an edge that reads as drawing without ever becoming a hard contour.

Nature Rendered Decorative: Toward The Patterned Surface

Although the motif is natural, the surface reads as a patterned fabric. The field of grass becomes a woven green with white knots; the sky, a broad textile of blue threads crisscrossed with lilac; the river, a belt of enamel. The decorative impulse does not flatten the world so much as reimagine it as a coordinated set of color areas. This tendency, which would later flower in Matisse’s interiors and cut-outs, emerges here in a modest register: the bank is a broad shape, the copse a saturated emblem, the horizon a band of chroma that ties the whole together. The result is an image that remains legible as landscape while already courting the pleasures of ornament.

Emotion, Symbolism, And The Psychology Of Color

The chromatic decisions transmit an emotional climate that outstrips literal description. Green, the color of life and renewal, dominates the right half and climbs upward, as if growth itself were pushing the composition. Purples and wine tones condense in the copse, giving it a slight melancholy, a gravity that steadies the buoyant scene. The pink-violet horizon suggests an interval of quiet between day and night, a tender hesitation. Moreover, the complementary friction of red and green, blue and orange, injects energy into stillness: the eye feels a pulse as it moves along the bank and across the water. Without invoking allegory, the picture stages a drama of vitality meeting rest, of flux met by steadfastness, and of solitude imagined as richly colored, not gray.

Relationship To Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, And Synthetism

The painting converses with several lineages at once. From Impressionism it inherits a commitment to open air and the translation of transient light into pigment. But the refusal to merely record optical sensation points toward Post-Impressionism. Cézanne’s constructive stroke echoes in the way Matisse builds planes with parallel marks; Van Gogh’s charged, directional brush appears in the urgent grasses and the sky’s swept textures; Gauguin’s Synthetism resonates in the contouring of large color areas and the willingness to let hue deviate from local color for expressive effect. Yet the canvas is unmistakably Matisse because the whole is poised rather than tormented, balanced rather than overworked. Color is not a cry of anguish; it is a grammar for making nature sing.

Echoes With Later Works And The Road To Collioure

Seen from the vantage of Matisse’s later career, this Garonne landscape is a rehearsal for the audacities of 1904–1908. The high-chroma greens anticipate the lawns and trees of Collioure; the violet-pink horizons prefigure the Fauve skies in which color is an expressive constant rather than a variable dependent on weather. The cropping at the top left, where a spray of leaves intrudes, foreshadows Matisse’s love of framing devices—curtains, screens, and branches—that punctuate his later interiors and landscapes. Even the faith in large, legible shapes anticipates the artistic economy of the cut-outs. If Collioure is the proclamation, the Garonne is the quiet manifesto.

Materiality: Pigments, Medium, And The Hand Of The Painter

Turn-of-the-century industrial pigments enlarged the artist’s palette, and Matisse makes use of their saturation: robust greens that can hold their own against reds, clear blues that maintain luminosity when dragged thin, durable violets unlikely in earlier centuries. He alternates between thin, swept passages and thicker impasto so that the surface breathes—areas of resistance next to areas of glide. The viewer feels the brush’s pressure shift as it negotiates grass, water, and sky. This tactility is not incidental; it is part of the meaning. The painting asks to be read not only with the eyes but with a memory of touch, as if walking a river path where ground, air, and water each have their own resistance.

Space, Depth, And The Window-Canvas Paradox

At first glance the painting offers depth: a foreground slope, a middle-distance path, a river that pinches toward a bend. But the more one looks, the more the scene compresses into a set of stacked bands. The violet horizon is a seam, and the sky descends as a near-flat field. The copse is a solid wedge that meets the sky without perspectival recession. Matisse plays the classic modernist game of having it both ways. He gives us enough cues to enter the space while simultaneously reminding us that the “space” is a construction on a single plane. This double awareness—of landscape and of painting—produces a gentle oscillation that keeps the image mentally active.

The Human Presence Without Figures

There are no people here, but the path, the cut of the bank, the fence posts, and even the softened track along the water imply human maintenance and passage. The river is a thoroughfare whether or not a boat is present in the frame. Matisse regularly chose such traces—chairs without sitters, tables without diners, shorelines without bathers—because they let him keep narrative at bay while preserving the sense of life. The absence of figures intensifies the viewer’s identification: we occupy the standing place, we feel the wind, we follow the ramp of the bank, we are the wanderer paused at a bend.

Nature Observed And Nature Invented

A fruitful way to look at the painting is to ask what is observed and what is invented. The bend of the river, the rise of the bank, the grouping of trees, the logic of light: these read as observed. The specific violets of the sky, the wine-dark copse, the saturation of the greens, and the emphatic red ground are invented to serve harmony. Observation provides the skeleton; invention provides the blood. That ratio—truth of structure, freedom of color—would become a defining feature of Matisse’s art. He never abandons the real; he liberates it to perform.

Rhythm, Movement, And The Viewer’s Path

The painting’s rhythm is not only visual; it is bodily. The diagonal bank leads our gaze and our imagined step. The alternation of long sweeps and short jabs in the brushwork quickens and slows our looking. The river’s narrowing sets an internal pace that the sky’s broad strokes counter with calm expanses. This is choreography in pigment. By the time our eye lands on the dark copse and rebounds across the water, we have enacted a silent journey—approach, pause, cross, return—that mirrors the experience of walking a riverside path at day’s edge.

The Decorative Ideal As A Form Of Clarity

Matisse would later describe his aspiration for an art of balance and serenity. Here, in an outdoor key, that ideal manifests as clarity. Every large zone has a task: the bank draws us in, the river carries us through, the horizon bathes the scene, the sky releases pressure, the copse anchors and deepens the chord. Nothing is redundant; nothing is over-specified. That economy allows the colors to resonate freely, like sustained notes in chamber music. The painting is restful without being dull, energetic without being chaotic, because each element has its intelligible role in the whole.

Why This Painting Matters

“Copse of the Banks of the Garonne” matters because it records the moment when Matisse’s eye and hand converged on a principle that would guide the rest of his career: paint not the incident but the lasting sensation. It is a humble subject elevated by the rigor of choice and the courage of experiment. In its union of observed structure, saturated color, and purposeful omission, the canvas announces a future where color will carry architecture and where the plane of the canvas will be a field of decisions, not a backstage for illusion. The river will flow on; the copse will keep its place; and painting, newly confident, will claim its own truth.