Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

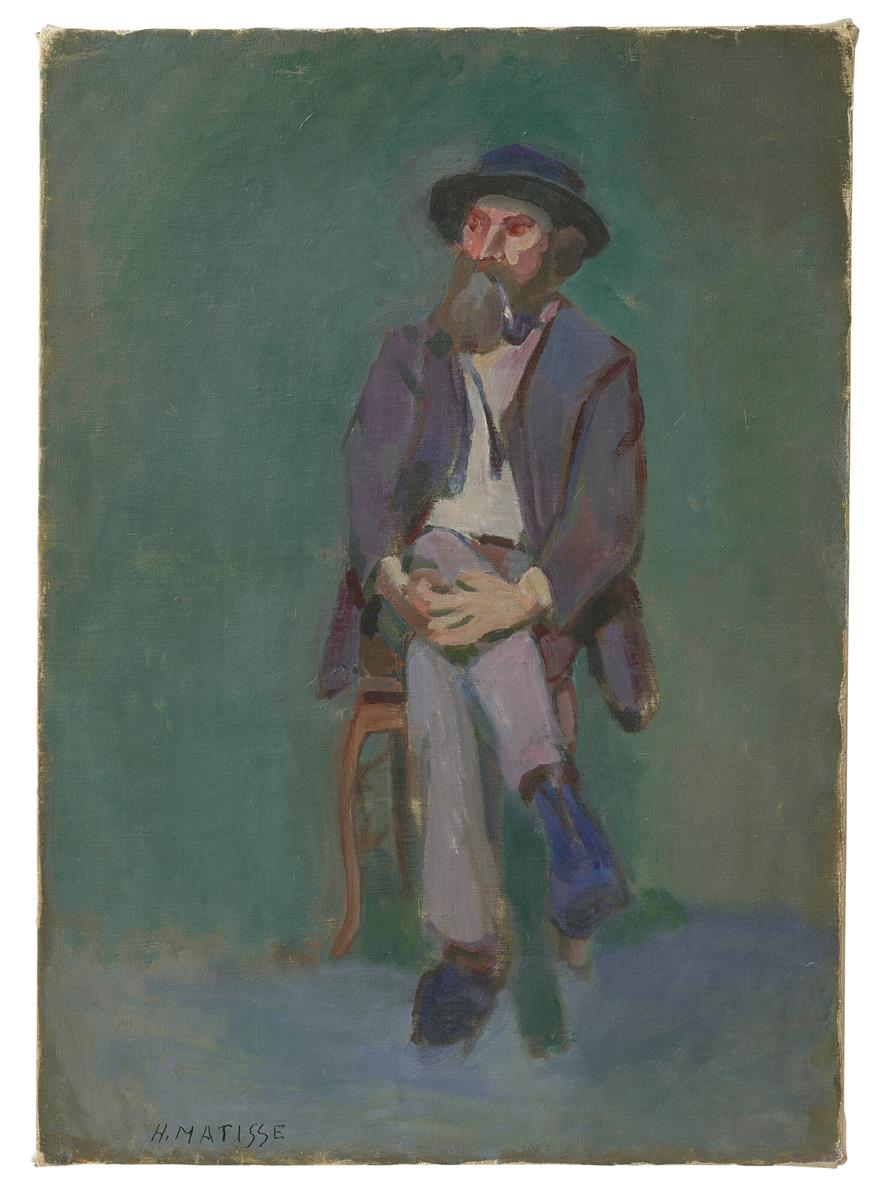

“Man Sitting” belongs to a pivotal moment in Matisse’s development. Around 1900 he was sifting through lessons from Cézanne, the Nabis, and the post-Impressionists, testing how color alone could construct a figure without fussy modeling. Rather than describing the sitter with academic contour, he blocks the body with measured, matte hues and lets temperature shifts—cool violet, grey-blue, moss green—carry the weight of volume and mood. The painting’s reserve is its modernity: it feels deliberate, economical, and quietly radical.

Subject and Setup

The motif is straightforward: a man in everyday clothes sits on a wooden chair, legs crossed, hands laced loosely over the knee. He wears a dark hat whose brim casts a soft wedge over the forehead and eyes; a short jacket and trousers in greys and violets; sturdy shoes that anchor him to a cool, bluish floor. There is no ornament, no anecdote, and little setting beyond a green wall lightly modulated by scumbled pigment. That spareness focuses attention on the body’s architecture—the hinge of the knees, the pyramidal mass of the torso, the sturdy oval of the head—so that structure, not storytelling, becomes the picture’s drama.

Composition: Stable Geometry, Quiet Asymmetry

Matisse builds the composition on a pyramid whose apex is the hat’s crown and whose base is the spread of the sitter’s feet. The crossed legs add a diagonal that energizes the otherwise frontal pose, while folded hands form a small node of interlocked shapes at the pyramid’s center. Slight asymmetries keep the figure alive: the right shoulder sits lower than the left; the tilt of the hat counterbalances the cross-leg; the chair’s rear leg appears as a faint vertical that steadies the frame. The sitter is moved off the canvas center to the right, leaving a green expanse on the left that functions as breathing space and emphasizes the forward thrust of the body.

Palette and Color Logic

The palate is restrained but strategic: greens for the field and shadows, violets and cool greys for clothing and flesh, deeper blue notes in the hatband and shoes, and a few warm accents in the face and hands. These families are not decorative choices; they are structural. The green ground is slightly warmer around the head, so the face—touched with rose and beige—seems to vibrate against it. The jacket’s violet flares cool where it meets the green, turns warmer along edges near the hands, and darkens in the inner sleeve. This temperature choreography models the form without resorting to black outline or brown chiaroscuro. The blues of the shoes and floor lock the lower half of the composition and echo cooler notes in the hat, keeping the color system coherent from top to bottom.

Light and Atmosphere

Illumination is broad and diffused, the kind of studio light that flattens cast shadows and emphasizes planes. Matisse suggests light not with a spotlight but with small value steps and local temperature shifts. The face glows because warm notes meet surrounding greens; trousers turn because grey slides toward lavender on the nearer thigh and toward blue-green in the receding calf. The room’s air is a single climate: nothing breaks the unity of mid-tone calm. That unity makes the painting feel contemplative rather than theatrical.

Brushwork and Surface

The brushwork is frank and unhurried. Passages are laid in with medium-loaded strokes that neither shout impasto nor hide the hand. On the wall, scumbling produces a slightly mottled field—thin paint dragged over an earlier layer—so that the ground lives without distracting texture. On the clothing, Matisse uses broader, flatter strokes that follow volumes: verticals along the coat fronts, diagonals across the thighs, small hinged touches at the knees and cuffs. The hands and face get the most nuanced handling but remain summary—no individual hairs in the beard, only decisive planes. This economy of means feels modern because the surface declares how it was made.

Drawing by Abutment

There is very little linear drawing. Edges are “found” where one color touches another: the hat’s brim appears where a dark blue-black meets a mid-green; the jawline emerges where warm flesh abuts cooler violet; the chair’s arc arrives as a brown ribbon pressing into the blue-grey trousers. This drawing by abutment allows Matisse to tune forms by easing temperatures rather than sharpening outlines, so contours breathe. The method also keeps figure and ground in the same atmosphere; no part is cut out or pasted on.

Space Without Perspective Tricks

Depth is shallow and convincing. The sitter feels forward because he carries the highest contrasts and more saturated notes; the wall recedes because its values are middle and its texture is thinner. A soft horizontal shift where the floor meets the wall implies a baseboard without spelling it out. The chair’s legs overlap the trousers and floor just enough to anchor the figure. With minimal data Matisse builds a room that is optically stable and psychologically intimate.

The Psychology of the Pose

Folded hands and crossed legs signal reserve, but not withdrawal. The body’s architecture is closed, yet the head tips slightly and the eyes—suggested with small, dark planes—look outward. The sitter’s beard and hat give him ballast and privacy; the hands, rendered with the greatest warmth, offer the human opening. The mood is not illustration of character so much as a climate—quiet, composed, alert. Matisse refuses anecdote and arrives at a broader truth: portraits can transmit interiority through posture, color, and tempo.

Clothing as Structure

Clothing is a vehicle for the palette and the figure’s mass. The coat’s violet carries weight and provides a dark envelope that separates torso from ground without a line. Thumbnail knuckles and cuffs—painted with small, warm planes—act as punctuation within the sea of cool tones. The trousers in cooler greys and blues create a stepping rhythm from knee to ankle, guiding the eye to the crossed feet and back again. Even the hat, with its shallow bowl and band of deep blue, is a structural cap: it physically completes the pyramid and chromatically echoes the shoes, closing the loop.

The Hands: Center of Gravity

Matisse gives the hands a special status. They are slightly warmer than the surrounding notes and a little more detailed, with interlaced fingers mapped by a few small planes of light and shadow. Because they sit at the composition’s center, they act like a visual hinge between upper alertness and lower repose. In a portrait of restraint, the hands provide emotion: their gentle knot implies patience, waiting, thought.

The Background Plane

The monochrome green field is not blank; it is a modulated, living environment. Near the head and shoulders the green lightens by a fraction, like a halo produced not by symbolism but by sensible light reflecting off flesh and shirt. At the bottom edges, cooler green mixes into the blue floor to keep the plane continuous. The wall could have been a neutral brown or a literal interior; by choosing green, Matisse both neutralizes the violet clothing and anticipates the Fauves’ fondness for colored grounds that act as active participants, not passive backdrops.

Dialogues with Influence

Cézanne’s constructive color is everywhere: planes of adjacent hue do the modeling; edges are less drawn than joined. From the Nabis, especially Vuillard and Bonnard, comes the courage to compress space and flatten the background into a decorative field. Gauguin’s simplified silhouettes and independence of color echo in the matte wall and firm outlines of hat and coat, though Matisse is subtler in temperature shifts. Manet’s sobriety—the dignity he could grant a seated figure with minimal description—lurks behind the pose. Yet the portrait is unmistakably Matisse in its calm tempo and its belief that color harmonies can serve psychology.

A Transitional Self-Discipline

If Matisse’s later Fauvist portraits explode with citrus and crimson, “Man Sitting” reveals the discipline that made those explosions coherent. He limits himself to cool families, avoids descriptive fuss, and builds the whole with a few big relationships: figure versus ground, warm flesh versus cool clothing, blue accents repeating top and bottom. The restraint is not caution; it is research. By 1905 he will amplify these chords into saturated symphonies, but the grammar is already here.

Material Decisions and Studio Practice

The painting’s skin suggests work done in passes. A thin, warm underpaint peeks at the edges, caught where the top layers stop short of the stretcher. Over that ground, Matisse laid the wall in broad scumbles, then built the figure with more opaque, cooler notes. Occasional pentimenti at the jacket hem and hat brim hint at adjustments—evidence of a painter steering the composition until geometry and mood locked. The final varnish, if any, seems matte; glare would contradict the work’s sober air.

Rhythm and Viewing Path

The eye enters at the warm face, slides down the beard into the knot of hands, travels along the diagonal thigh to the blue shoes, and returns via the chair leg and coat sleeve to the head. That loop is intentional: Matisse sets warm accents (face, hands) as waypoints within a large system of cools so the viewer always finds the person amid the architecture. The painting is slow to look at and slow to reveal; its pleasures aggregate with time.

What the Work Says About Modern Portraiture

“Man Sitting” quietly revises the contract between portrait and likeness. It offers no anecdotal props, no literate background, no sparkling brush gymnastics. Instead, it proposes that likeness resides in posture, proportion, and the harmonies a person brings into a room. The sitter’s identity, whether known or anonymous, matters less than the human weight of a body at rest and a mind turned inward. That shift—from naming to being—is a decisive step toward modern portraiture’s autonomy.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Placed beside the darker Breton interiors of 1896–98, this canvas is cleaner in structure and cooler in mood. Set against the riotous chroma of “Woman with a Hat” (1905) or the Nice interiors of the 1910s–20s, it looks austere but foundational. The later freedom to let a green face or red shadow stand will grow from the confidence developed here: that a figure can be both solid and tender when built from frank color planes.

How to Look Slowly

Begin at the hat: note how a deep blue band stabilizes the brim against the green. Move to the eyes—just a few dark planes under a cool brow—and feel how little information still convinces. Trace the beard’s wedge into the warm throat patch, then down to the interlaced fingers; watch how small pinks and beiges push against the violet cuff. Follow the long diagonal thigh, sensing the shift from lavender to blue-grey as the leg turns away. Pause at the shoes; notice their denser blue, the firmest notes in the picture. Finally, step back and let the green wall reassert itself as a single, moderating field that holds every decision in equilibrium.

Legacy and Significance

“Man Sitting” matters because it distills portraiture to essentials at the threshold of a new century. It treats color as structure, background as active plane, and brushwork as transparent evidence rather than virtuoso display. It absorbs influences without mimicry and points directly to Matisse’s later audacity. The painting feels modest, but its lessons are large: that you can achieve presence without description, intimacy without narrative, and gravity with a handful of tuned colors.

Conclusion

In “Man Sitting,” Henri Matisse turns a seated figure into a study of poised relations—between warm and cool, figure and ground, weight and air. The portrait’s dignity comes from its clarity: a strong pyramid of form, a disciplined palette, and a continuous atmosphere that binds person and room. Without flourish or spectacle, it shows a young painter inventing the methods that will soon transform modern color. The sitter rests; the painting thinks.