Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

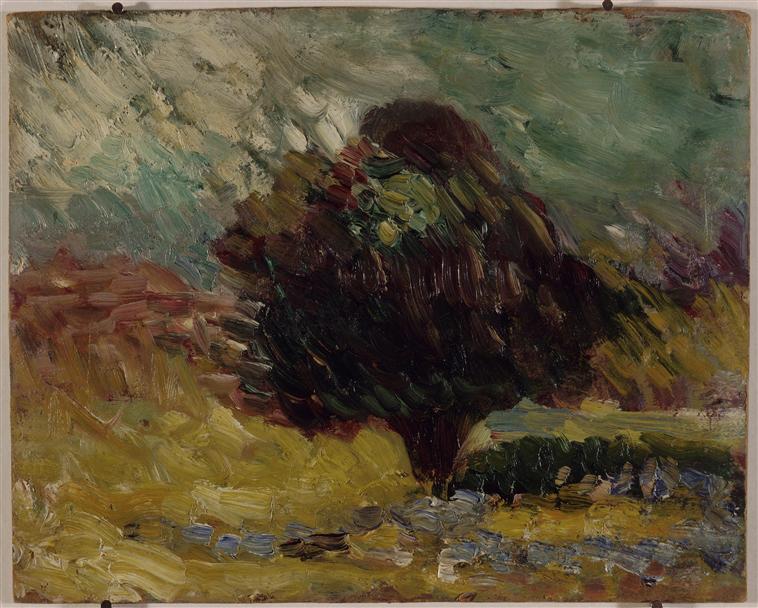

“The Olive” is a compact manifesto for what Matisse was discovering at the end of the nineteenth century: color and stroke can shoulder the entire job of painting. In this picture, nothing is described by linear contour. Instead, the tree, the field, and the sky arrive where neighboring hues meet at tuned values, and the touch itself performs substance. The panel’s modest size intensifies the effect; the paint sits thick, the strokes are legible, and the whole image reads as an immediate translation of looking into a material grammar. What could have been a quiet motif—a single tree in a pasture—becomes a study in how to build weather, weight, and depth with pigment alone.

Historical Context

The date 1898 places the work at a critical pivot in Matisse’s development. Having moved beyond the dark, tonal still lifes of his academic period, he was absorbing the southern light of Corsica and the Midi, studying Cézanne’s constructive color, the Nabis’ tapestry-like surfaces, and the Divisionists’ belief in the vitality of broken brushwork. He would not become a doctrinaire follower of any method; rather, he distilled a personal practice: chromatic darks instead of black, living whites and greens that receive nearby tints, and edges that arise from abutment instead of outline. “The Olive” demonstrates that shift applied to landscape. Its palette is restrained but strategically hot and cool; its surface, alive with directional marks, reveals a painter turning sensation into structure.

Subject and Motif

The subject is deceptively simple: a mature olive tree set slightly left of center, its canopy dense and rounded, its trunk rooted in an ochre field. A short berm or hedge traverses the middle ground at right, and a skein of stones or scrub punctuates the foreground. Above, a roomy expanse of sky tilts toward green and turquoise, rolled by wide, sweeping strokes that imply wind. There is no figure, building, or narrative prop. The tree is protagonist, environment, and weather vane. Matisse asks the viewer to experience the scene not as a catalog of objects but as an interlocking system of forces—weight pressuring ground, wind combing air, light tinting everything it touches.

Composition and Armature

The composition balances a dominant vertical mass—the tree—against horizontal flows of field and sky. The trunk plants a dark wedge at the center bottom then blooms outward into an oval canopy whose left edge grazes the picture’s midline. This vertical body is countered by the thin dark band at right, which reads as hedge or shadow, and by a low string of slate-blue marks across the foreground that steadies the base. The sky’s broad, diagonal sweeps cross behind the tree, enlivening the background without breaking the central hold. The result is poised: the mass of the olive secures the image while lateral rhythms keep it from becoming static.

Color Architecture

Color is the engineering that holds firm. The ground is a chord of warm ochres, raw siennas, and mustard notes, cooled by flicks of blues and lilacs that suggest stones or shadowed tufts. The tree’s body is a compound dark—deep bottle green tempered by maroons and blue-blacks—dense enough to carry weight yet alive with internal modulation. In the canopy, small citrons and blue-greens glint like pockets of light among leaves. The sky is not simply blue; it is a mix of turquoise, gray-green, and pale celadon dragged thin so the warm undertone hums through, creating the sensation of sunlight diffused by moving cloud. Because each zone contains both warm and cool notes, the scene breathes; no passage dies into monotone.

Light and Atmosphere

Illumination is broad and weathered rather than theatrical. There is no single spotlight; instead, light operates as a temperature system. Warmer notes advance, cooler ones recede, and their calibrated meetings construct volume. The tree appears solid because warmer greens and burgundies swell toward us while cooler strokes sink back, implying a rounded mass pierced by glints. The field feels sun-bleached in places and damp in others, not because of descriptive detail but because ochres are alternately heated and cooled. The sky reads as agitated air—its long strokes swerve, layer, and shear—so we sense wind as much as light.

Brushwork and Impasto

Matisse gives each element a distinctive handwriting. The canopy is knit from muscular, arcing strokes that radiate around a center, like growth rings made visible. The trunk and deepest shadows are laid with heavier, vertical pulls, building a compact column that anchors the mass. The field is handled with flatter, lateral strokes that lie down like matted grasses; now and then a thicker daub stands upright as a tuft or stone. In the sky, broader scrapes run diagonally, their edges feathered so the movement feels continuous and airy. The impasto matters. Ridges catch actual light and change as the viewer shifts position, animating the picture even further and echoing the subject’s constant motion.

Drawing by Abutment

The painting contains almost no linear contour. Forms are “drawn” where one color abuts another at a tuned value. The tree’s silhouette is simply the seam where its dark, warm greens meet the cooler sky. The hedge reads because a deep band presses against paler ground. Stones appear where small slates of blue and violet interrupt the yellow. This method keeps every part in the same atmosphere, allowing Matisse to refine shapes by warming or cooling their boundaries rather than hardening them with lines. It is precisely this strategy that will later allow his most saturated canvases to retain clarity.

Space and Depth Without Rulers

Depth is achieved by the stacking of planes and the procession of temperatures. The foreground yellows are thicker and slightly cooler, the mid-field warms and thins as it recedes, the hedge sets a mid-distance register, and the sky opens beyond with the palest values. Overlaps do the rest: the canopy eclipses the sky, the hedge cuts behind the trunk’s base, and the stone row overlaps the field. The space is shallow yet convincing—true to the felt distance of looking across a small meadow toward a single tree.

Wind, Weather, and Movement

Perhaps the most striking sensation is movement. The sky’s diagonal strokes arc in the same general direction, as if a steady wind were combing clouds. The canopy’s marks respond—swept crescents at the edges, tighter loops within—so the tree seems to absorb and redistribute force. Even the ground contains motion; the brush drags left-to-right and right-to-left, like grass flattened and raised by gusts. The effect is not theatrical; it is embedded in the syntax of the brushwork. Matisse translates wind into a choreography of marks that carry the rhythm of air across the whole surface.

Materiality and Ground Tone

A warm undertone glows through thin passages, particularly in the sky and along the field’s paler scrapes. Allowing this ground to peep through binds the palette and keeps cool colors from going chalky. Where mass is needed—the trunk, the core of the canopy—paint stands highest. Where air is needed—the upper sky and distant field—paint thins and scumbles. The alternation between density and veil feels like the alternation between pressure and release in nature: weight at the earth, breath in the air.

Dialogues with Influences

“The Olive” speaks with several contemporaries while retaining Matisse’s voice. From Cézanne comes the conviction that volumes turn through adjacent planes of color; one feels it in the canopy’s modeling. From the Nabis—Bonnard and Vuillard—comes the comfort with intimate scale and the willingness to let background planes participate actively in composition; the field and sky here are as much patterns of touch as descriptions of place. The Divisionists supplied the idea that broken color could energize a surface, but Matisse rejects a standardized dot; his marks flex in length and pressure to suit growth, wind, and ground. A comparison to Van Gogh is also tempting—especially in the weather-charged sky—but Matisse’s equilibrium is different: steadier cadence, fewer extremes, greater emphasis on structural balance.

The Olive as Emblem

Olives are not generic trees. They carry small, reflective leaves and dense, twisting growth that throw off color in specks rather than broad lamina. Matisse captures this character through the canopy’s mosaic of greens streaked with citron and teal. The tree’s dark core never deadens because it is punctuated by these small lights. The trunk, though compact, suggests age and toughness; it expands at the base like a wedge that grips the earth. Without literal detail, the painting conveys the olive’s temperament—tenacious, drought-tolerant, a living knot that has weathered seasons.

Psychological Register

Though unpeopled, the painting feels inhabited by weather and attention. The dark, central mass reads as resolve; the sweeping sky suggests restlessness; the yellow field carries stored heat. The tiny slates of blue in the foreground introduce coolness, like a line of stones damp from a spring or a path that briefly shadows the grass. The mood is neither idyllic nor ominous; it is alert calm, the sensation of standing in wind where everything has weight and nothing is still.

How to Look Slowly

Begin at the lower edge where the slate-blue notes punctuate the ochre. Notice how those cools settle the palette and form a low horizon for the eye. Rise into the trunk and feel the shift to thicker, warmer darks. Let your gaze circle through the canopy; see how strokes bend, overlap, and change temperature to imply depth without a single drawn line. Slip outward to the edges where the canopy thins and the sky’s color pushes through—those small breaches are the picture’s breathing. Finally, step into the sky and follow the long, diagonal scrapes until you sense their rhythm carrying you back toward the tree; the painting teaches the path your eye should take.

Scale, Speed, and the Act of Painting

The work’s likely small size and the directness of its strokes suggest a swift execution, perhaps en plein air. That speed is not carelessness; it is a commitment to a specific tempo of seeing. The panel holds the interval of a breeze, the rate at which clouds pass, the way a tree’s dark mass shifts when light changes. Matisse’s decisions—where to thicken, where to glaze thinly, where to interrupt with a cooler note—read as a sequence rather than a diagram, inviting viewers to reconstruct the act of painting as they look.

Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Alongside the Corsican and Toulouse canvases of 1898, “The Olive” proves that Matisse’s new grammar works outdoors as well as on the still-life table. The essentials are present: chromatic darks that remain alive, edges born at seams, forms that turn by temperature rather than by hatch, and a reliance on a few commanding shapes to govern many small incidents. These habits will support the heightened saturations of 1905. When the palette later blazes into pure cadmiums and viridians, the compositions hold because their scaffolds were rehearsed in concentrated studies like this one.

Conclusion

“The Olive” is more than a tree in a field; it is an engine of color relationships, a record of weather translated into touch, and an early proof that painting can build a world from tuned intervals. A dark mass anchors the center; a yellow ground breathes heat; a blue-green sky sweeps with motion. No outlines bind the forms; edges appear where warms and cools negotiate place. Impasto gives weight; scumble gives air. The picture’s quiet triumph lies in its equilibrium: everything moves and everything holds. In this small, forceful panel, the young Matisse discovers a language that will carry him into the radiant clarity of his mature art—a language in which color thinks, brushwork sings, and a single olive tree can contain an entire weather system.