Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

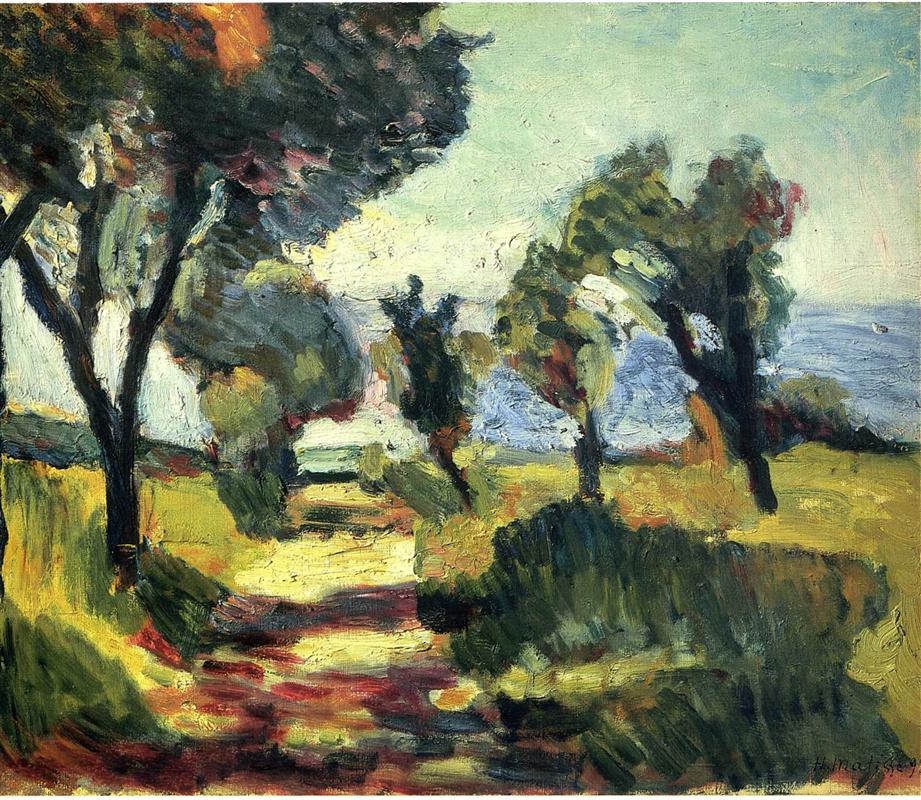

“Olive Trees” belongs to the breakthrough year of 1898, when Matisse recalibrated his vision under southern light. The motif is simple—a dirt path threading a grove beside a shimmer of blue water—but the method is radical. Forms are not belabored by outline; they are discovered where colors meet. A few large masses govern the surface: the high, pale sky; the dark, wind-bent trees; the hot field; the cool, rutted path. With these elements tuned into a single atmosphere, Matisse turns ordinary daylight into structure and mood.

Historical Moment and Significance

By the late 1890s, Matisse had absorbed lessons from academic training and from the tonal sobriety of his Breton works. Corsica and the Midi introduced a harsher, clearer sun that bleached fields to lemon and pushed shadows toward blue-violet. “Olive Trees” records this conversion. Instead of brown shadows and gray whites, the canvas hosts chromatic darks and inflected lights. The result is not merely a brighter palette; it is a new logic in which color bears the weight of drawing, modeling, and space. The painting thus stands as a hinge between post-Impressionist observation and the fearless harmonies of Fauvism.

Motif and Vantage

Matisse places us on the path itself, slightly below the horizon. The way narrows into the distance, hedged by shrubs and trunks that tilt with wind pressure. The left tree looms, its canopy overhanging the path; three smaller trees step back on the right, their silhouettes bending toward the sea or sky beyond. The viewer’s body is implicated: you can feel sun on the right cheek, cool shadow on the left, grit underfoot. This pedestrian vantage collapses spectacle into intimacy, letting the composition be read as a sequence of tactile zones rather than distant scenery.

Composition: A Corridor of Light

The design hinges on a corridor of yellow-white light running through the middle. Darker flanks—bushes and trunks—press inward, carving the path and propelling the gaze. Above, a broad wedge of sky opens the space, while canopies billow across the top edge like a parted curtain. The composition reads as three registers: foreground path, mid-ground grove, distant strip of blue. Their boundaries are never hard lines; they are negotiated seams where temperature and value shift. The painting breathes because these seams remain active.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Color organizes everything. The path is a mosaic of butter yellow, peach, and cool mauve, with small maroon notes that suggest ruts and stones. The grasses on either side carry sap green and olive pushed warm by sunlight; where shade gathers, greens cool toward teal and spruce. Tree trunks are not dead black; they are chromatic mixtures—blue-black, green-black, and wine-brown—alive enough to catch glimmers from the path. The sky is a pale veil of turquoise and cream, ventilating the heat below. A narrow band of intense blue at right hints at sea or distant hills and functions as a cooling counterweight to the field’s hot chord.

Light Without Theatrics

Rather than spotlight effects, the painting offers a field of illumination. Light is conveyed by temperature, not by photographic glare. The sunlit path advances because its yellows are warm and high in value; the shaded margins recede because they cool and darken. Highlights in the foliage are creamy, not chalk white, so they belong to the same atmosphere as the grass. The distant blue is thinly scumbled, allowing the under-color to glow through—precisely the optical sensation of bright air seen between leaves.

Brushwork and the Performance of Nature

Matisse tunes his touch to each substance. The path is laid with short, dragged strokes that flatten slightly, mimicking packed earth. Grass is built from tufted, directional dabs that flick upward and sideways, catching the wind’s lean. Trunks receive longer, muscular pulls whose thickness varies at knots and forks, giving them weight without descriptive bark. Canopies intermingle small, rounded strokes with quick scrapes, so highlights ride the ridges like sun on leaves. The stroke itself becomes description: the grove feels windy not because flags wave but because marks slant and accumulate in gusts.

Drawing by Abutment

Edges are discovered where hues and values meet. The left trunk materializes where a deep blue-green presses against the pale sky; the right-hand trees are defined by the clash of cool silhouettes and warm fields; the far hedge is a seam between olive and turquoise. This “drawing by abutment” keeps all parts under one light and allows micro-adjustments: warming a boundary brings it forward; cooling it sends it back. The method produces forms that feel observed yet unforced.

Space Built from Intervals, Not Rulers

Depth arises from value steps and texture, not plotted perspective. The foreground path is saturated and thick; mid-ground strokes loosen and lighten; the far blue band thins and cools. Overlaps confirm the recession: bushes cut in front of trunks, canopies cross the sky, the path slices behind a dark clump before reappearing. The eye walks the painting by crossing temperature thresholds—warm to cool, thick to thin—just as it would in the grove.

Rhythm and Movement

The painting moves like a measured dance. The path leads in a chain of light patches; shrubs push back like beats; trees swing overhead in counter-rhythm. The alternation of warm and cool acts as a metronome. Reds and oranges flicker where trunks meet grass, accelerating the tempo; broad, cooler swathes in the sky slow it. The composition feels musical because its elements repeat with variation: verticals (trunks), rounded masses (canopies), and horizontal bands (path, horizon) sound against one another.

The Olive as Emblem

Matisse’s trees are not anonymous; they are olives with their particular character. Unlike oaks or poplars, olives carry dense, silvery leaves that scatter light; their trunks twist, not soar. Matisse suggests both traits economically. The canopies are modelled not by shadow masses but by specks and scrapes of green, yellow, and pearl, giving the impression of reflective, small leaves. Trunks swell and angle like living muscles. The olive’s hardiness—its ability to thrive in stony heat—echoes the painting’s chromatic resilience: darks remain alive, lights remain warm, and the whole survives the sun.

The Path as Psychological Device

The central path is both motif and metaphor. It structures the image and guides the eye, but it also proposes an attitude: forward motion moderated by shelter. The left canopy overhangs like a protective arm, while the open right side hints at exposure to sea and sky. This balance of safety and openness matches the painting’s emotional temperature—alert calm, the pleasure of walking under moving shade toward bright air.

Living Whites and Chromatic Darks

Two technical choices sustain the harmony. First, whites are never pure; the highest values are tints—lemoned, blued, or warmed by peach—so highlights glow rather than glare. Second, darks are chromatic; rather than dead brown or black, they contain color, which keeps the surface breathing and allows dark forms to converse with light ones. These habits will become signatures of Matisse’s mature practice, enabling later, hotter palettes to remain balanced.

Dialogues with Near Neighbors

“Olive Trees” converses with several models while remaining unmistakably Matisse. From Cézanne comes the conviction that volume is constructed from adjacent patches; the trunks and canopies turn where color planes meet. From Van Gogh comes the sense that trees can be gestures and that chromatic darks are more alive than bitumen; yet Matisse steadies the rhythm and tempers agitation with design. From the Neo-Impressionists he borrows the energizing effect of juxtaposed strokes, but refuses mechanical division; his marks vary length and direction to match substance and wind.

Materiality and Ground

A warm undertone—ochre leaning to red—hums beneath thin areas, particularly in the sky and along the path’s pale scrapes. Allowing this ground to show binds the palette and prevents blues from turning chalky. Where mass is needed—bases of trunks, thick shrubs—paint piles into low impasto, catching literal light like sun on bark. Where air is required—upper sky, distant band—pigment thins, letting the canvas weave participate in the sensation of bright atmosphere.

How to Look Slowly

Stand back until the scene resolves into three great fields: pale sky, dark trees, hot ground. Feel how those masses balance. Step closer and study the seams: the warm edge where the left trunk meets light; the cool shadow that pools at the path’s bend; the lavender note under a canopy that suddenly makes heat believable. Trace the stroke directions: they arc with wind, lean with trunks, and flatten with earth. Then step back again and allow the picture to read in one glance—a midday experience compressed into tuned relations.

The Work’s Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Within the 1898 sequence—Corsican seascapes, Toulouse façades, intimate still lifes—“Olive Trees” demonstrates how portable Matisse’s new grammar had become. Whether faced with fruit on a table or wind in a grove, he organizes reality into a few commanding shapes, tunes warm–cool relationships at their boundaries, and lets brushwork perform substance. This clarity of structure will carry the blazing chroma of 1905: when the palette later leaps to cadmium fire, the compositions remain legible because they were engineered on canvases like this.

Conservation and Surface Reading

Even in reproduction one senses varied thickness. Ridges across the canopies catch highlights and imply flicker. Thin scumbles at the top allow under-color to breathe, giving the sky a dry, airy quality. Scraped passages along the path read as quick corrections that leave history visible. These material cues matter; they situate the viewer at the painter’s tempo, making process part of perception.

Lessons for Viewers and Painters

For the viewer, the painting models how to notice: light as temperature, shade as color, edges as negotiations. For painters, it demonstrates that a few large relations suffice to carry complexity. If the path glows against flanking cools, if trunks are chromatic and canopies broken by living whites, the scene will persuade without laboratory detail. “Olive Trees” is a primer in building a landscape that feels both observed and invented.

From Observation to Construction

What finally makes the canvas compelling is its refusal to choose between faithful seeing and formal invention. The grove’s distinctive qualities—the olive’s leaf sparkle, the hot path, the breeze—are believable. Yet the design reads as a considered arrangement: corridor, counter-shapes, cadence of verticals. Matisse proves that construction does not betray nature; it clarifies it. By editing to essential relations he finds the inevitability beneath appearances.

Conclusion

“Olive Trees” turns a midday walk into a persuasive system of color, stroke, and plane. A yellow corridor anchors the ground; dark, bending trunks stabilize and energize the field; canopies breathe with living whites; a thin, cooling band of blue releases the heat. Edges arise where hues meet; space unfolds as a ladder of temperatures; brushwork performs the wind. In this grove the young Matisse discovers the grammar that will support his most daring color: that when relations are exact, paint can shoulder light, volume, and feeling all at once—and make the world feel both newly seen and utterly inevitable.