Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

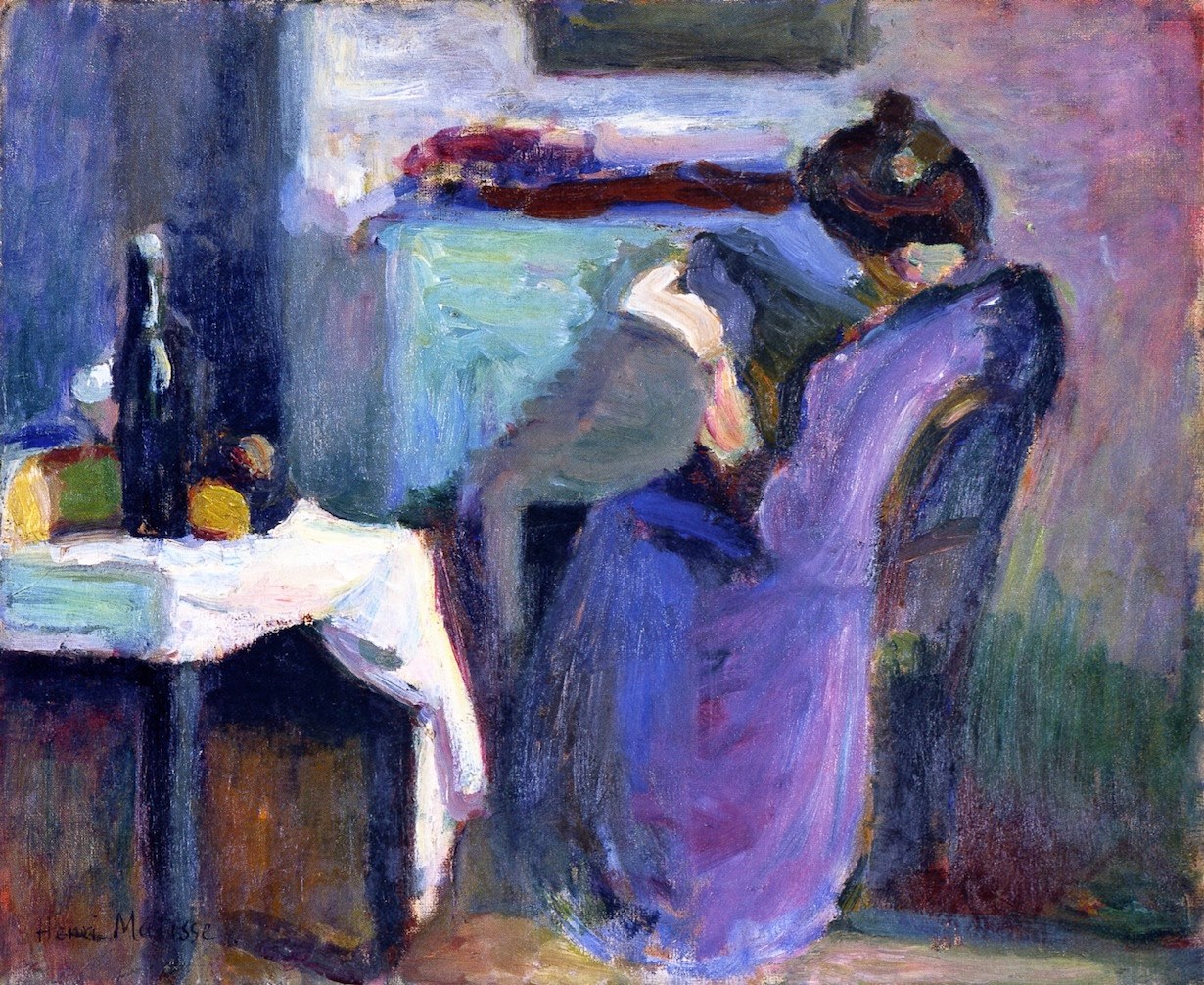

“Reading Woman In Violet Dress” belongs to the key year of 1898, when Henri Matisse shifted decisively from tonal modeling to a language in which color organizes space, light, and emotion. The subject is unassuming: a woman absorbed in a book, a corner of a room, a table with a few objects. Yet the painting reads like a manifesto. Planes are arranged as chromatic fields, edges arise where colors touch, and the entire interior seems to breathe one atmosphere. What might have been a sentimental genre scene becomes a demonstration of how painting can simultaneously describe and invent reality through hue, value, and touch.

The Poise of the Motif

The composition is built around a poised triangle: table at left, figure at right, cool wall and mantel stretching across the middle. The woman sits turned inward, her head bent, hair pinned, the long sweep of her violet dress providing the canvas’s most continuous shape. The table’s white cloth interrupts the darker left side like a wedge of light, leading the eye toward the reader before it returns to the glimmering mantle and picture rail. A bottle and fruit function less as still-life details than as tonal anchors, giving the light cloth weight and balancing the large violet form across the center.

Composition as a System of Planes

Rather than draw contours and fill them, Matisse constructs the room from interlocking planes. A vertical band of ultramarine at far left sets the key for the left wall. A cool green-blue mantel steps forward as a broad horizontal. The violet figure occupies a diagonal wedge that carries the gaze from the bottom edge up to the head and back into the interior. Behind her, a mauve-pink wall absorbs and releases light, turning gently cooler near the floor. The viewer experiences the space as a sequence of chromatic fields that meet at seams—table against wall, dress against chair, face against shadow—each seam calibrated to carry both form and depth.

Color Architecture: Violet as Protagonist

The painting’s center of gravity is the violet dress. Matisse pitches it in a range from blue-violet shadows to warmer lilac highlights, enriching it with small inflections of rose, emerald, and cobalt that keep it alive. Across from this large cool mass he places the white cloth tinged with pinks and greens, so the two planes speak across the room. The bottle stands as a chromatic dark—green-black rather than brown—while the lemons strike brief notes of yellow that lift the whole harmony. Around these actors, the walls swing between teal, sea-green, ultramarine, and mauve, so the atmosphere is not neutral gray but an active participant in the drama.

Light as Temperature, Not Spotlight

There is no theatrical beam of light. Illumination is conveyed by temperature shifts and by the thickness of paint. The tablecloth glows because it carries more white and sits against a dark wall; the dress catches light where violet warms toward lilac; the face, hands, and book are described by the quietest contrasts—cool shadows against small warm notes—so the figure’s attention feels inward and sustained. This choice rejects anecdotal realism in favor of convincing sensation: the room seems evenly lit, with colors gently re-keyed by proximity rather than by a single source.

Brushwork and the Tactile Logic of Surface

Matisse varies his touch to suit substance. On the cloth he lays broad, creamy strokes that turn at the hem and fold over the table’s edge, catching literal light on the ridges. The bottle is shaped with denser, vertical pulls that suggest glass without counting reflections. Fruit is marked by rounder, more saturated dabs that carry ripeness. The dress is written with long, slightly curving strokes, their direction tracing the fall of fabric from shoulder to lap. Walls and mantel are scumbled thinly so the color breathes and the weave of the canvas participates, evoking air rather than objects. Every choice of touch advances the description while maintaining the painting as an object in its own right.

Drawing by Abutment

Edges throughout are created by the meeting of colors at the right value rather than by linear outline. The reader’s profile exists where a pale note touches a cooler shadow; the book’s edge appears because a slightly warmer plane meets the cool of the dress; the table’s corner sharpens where white abuts ultramarine. This “drawing by abutment” keeps everything under a single light and allows the painter to adjust form with chromatic decisions. If the sleeve must advance, he warms its edge; if the wall should recede, he cools and grays it. The method also lets edges soften naturally, mirroring the way the eye perceives in a dim interior.

Space Without Diagram

Depth is built from plane stacking and value steps rather than from plotted perspective. The table occupies the nearest field through its high contrast and impasto. The figure sits slightly back, its edges softer where dress meets chair and floor. The mantel recedes by cooling and thinning, then the space climbs to a higher shelf and a dark band below a frame. Nothing is mechanically measured, yet the room feels inhabitably deep. The viewer’s eye moves from near to far by crossing temperature thresholds more than by following converging lines.

The Psychology of Absorption

The subject of reading invites the depiction of inwardness, and Matisse delivers without resorting to facial detail. The head bends; the hand supports the book; the rest of the body flows into a single violet arc. The choice of color intensifies the mood: violet, hovering between warm and cool, dignifies calm concentration. The book’s pale pages become a small, bright field around which the painting’s largest mass—her dress—organizes itself. In refusing anecdotal specifics, Matisse gives the figure a universal quality: anyone who has been captured by a text recognizes the posture, the hush, the slight forward lean into thought.

The Table as Counterpart

At first glance the still life on the table seems incidental, but it plays an essential structural role. The white cloth and dark bottle provide the strongest value contrast, anchoring the left third of the canvas. Their vertical and horizontal orientations balance the sloping line of the seated figure. Chromatically, the bottle’s green-black and the lemons’ yellow oppose the dress’s violet on the color wheel, energizing the whole composition. With minimal marks—no label, no counted highlights—Matisse makes the tabletop both believable and abstract, a stage where color proves its weight.

Interior Atmosphere and the Legacy of the Nabis

The humid, saturated color and the subject of domestic quiet resonate with the interiors of Bonnard and Vuillard, artists Matisse admired. But where the Nabis often dissolve forms into decorative pattern, Matisse insists on large, legible volumes and a clear scaffold of planes. The picture is intimate without being fussy, decorative without losing structure. This balance between lyric color and formal clarity will become a signature of his interiors and, later, of his cut-outs.

Dialogues with Cézanne and Van Gogh

From Cézanne, Matisse borrows the conviction that form can be constructed from adjacent color patches—see how the dress turns where cool violets meet warmer lilacs. From Van Gogh he inherits chromatic darks and the expressive authority of brushwork—note the bottle’s green-black or the scumbled wall. Yet the temperament here is distinct: steadier than Van Gogh, more open and airy than Cézanne’s studio confines. The painting holds its equilibrium even as color takes the lead.

The Role of White

Matisse’s “whites” are never neutral. The tablecloth carries blushes of pink and mint where surrounding colors reflect into it. The book’s pages are touched with pearl-gray so they sit in the same atmosphere. Even the small strip of light along the mantel is not pure white but a cooled tint, allowing it to glow without piercing the harmony. These living whites prove how the painter understands light: not as a chemical glare but as a field of relations.

From Observation to Construction: A Step Toward Fauvism

Although the palette is more moderated than it would be in 1905, the logic here already belongs to Fauvism. Color is structural; shadows are chromatic; edges are seams; whites are alive; the surface remains visible as paint. Intensify the violet a few steps, push the wall’s mauves toward magenta, clean the ultramarines, and the composition would still hold because its scaffolding is exact. The later blaze of color is thus not a leap into chaos but an amplification of principles tested in works like this.

Gender, Labor, and Modern Domesticity

The figure’s absorption in reading—rather than sewing, cooking, or posing—quietly modernizes the domestic interior. Reading signifies agency and self-directed time. The dress’s dignity and the chair’s firmness resist sentimentality. Yet the painting avoids polemic; it attends to the person before it. The dignity comes from the way elements relate: the table’s weight supports the figure’s inward bend; the room’s coolness calms the bright whites; the violet mass commands the center without demanding theatricality.

Materiality and the Warm Ground

A warm undertone glows through thin passages—notice it at the table’s edge, along the dress’s hem, and in scumbled areas of the wall. This ground unifies disparate hues and prevents blues from going chalky. Where solidity is needed—the bottle, the elbow, the lower folds of the dress—paint gathers into thicker ridges that catch literal light. Where the room must breathe—the mantel, the far wall—it thins, letting the weave of the canvas support a sense of air. The surface, like the scene, alternates between weight and breath.

Rhythm and Movement

The eye traces a gentle circuit: up the table leg, across the white cloth, along the bottle to the shelf, down the mantel’s turn, into the bowed head and along the violet sweep to the floor, then back to the table. This movement is reinforced by recurrent shapes—a trio of rectangles (table, mantel, book), a sequence of arcs (chair back, shoulder, dress), and echoing chromatic events (white cloth and book pages; dark bottle and hair). The rhythm is musical rather than mechanical, a balance of sustained fields and quick notes.

How to Look Slowly

Stand back first until the painting collapses into four major fields—deep blue left wall, cool green-blue mantel, violet figure, mauve right wall. Feel how these planes hold each other in equilibrium. Step closer and find the seams: the warm edge where violet meets green, the pale hem folding over dark, the cool shadow under the table that keeps it grounded. Look at the bottle’s top: it is just a few green-black strokes and a slender highlight, yet it conjures glass. Return to the face and hand; see how little is stated, how much is implied by value transitions. Finally, let your eyes rest in the quiet triangle of book–head–lap, the heart of the painting’s psychology.

Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Alongside the Corsican seascapes, Toulouse façades, and intimate still lifes of 1898, this canvas shows Matisse testing whether his new grammar—color as structure—functions indoors as well as out. It does. The same principles that build cliffs and groves also build a person in a chair under lamplight. In later interiors, he will open windows to blazing gardens and flatten patterns into bold harmonies. “Reading Woman In Violet Dress” is a stepping stone: modest in scale, ambitious in method, and already unmistakably his.

Conclusion

“Reading Woman In Violet Dress” turns a simple act—reading—into a complete world made of color. A violet sweep holds the center; whites glow with neighboring tints; blues and greens cushion the eye; a few dark notes supply gravity. Forms are not fenced by lines but born at their boundaries. Space is not plotted by rulers but stepped through by chromatic intervals. The painting persuades because its relations are exact and humane. In this quiet room, Matisse rehearses the language that will soon make him a leader of modern color—and preserves, for us, the timeless hush of a person lost in a book.