Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

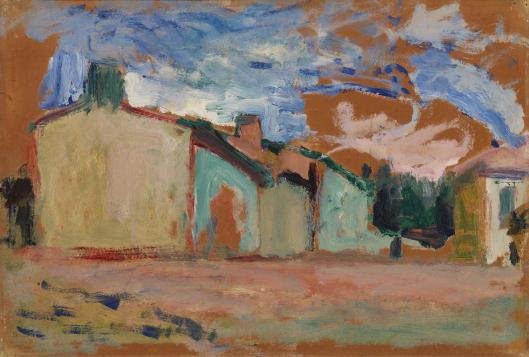

“Houses,” painted in 1898 at Fenouillet near Toulouse, looks disarmingly simple: a few buildings, a big sky, and an open foreground. Yet from the first glance it is clear that the canvas is not a transcription of architecture but a proposal about painting itself. Matisse stages the world as a meeting of large, breathing planes—walls, roofs, street, and sky—laid over a glowing ochre ground. Edges are not drawn; they occur where one color meets another at the right value. The sky is not a backdrop; it acts like an equal partner, its clouds written in swift blue and rose strokes that push against the masonry below. In this deliberately spare setting the painter tests how far he can economize description and still deliver solidity, air, and light. The answer is very far indeed.

Historical Context

The late 1890s were a hinge for Matisse. After academic training and somber still lifes, he spent 1896–97 simplifying rugged Brittany motifs into interlocking planes. When he turned south in 1898—to Toulouse, Corsica, and other Mediterranean climates—his palette brightened and his brushwork thickened, reacting to drier air and higher, whiter light. “Houses” sits squarely in this pivot. It shares with the Corsican landscapes a warm, active ground and with the Toulouse pictures a fascination with façade and sky as complementary actors. Above all it announces a structural principle that will carry into Fauvism: color is not a decorative glaze; it is the material of construction.

Motif and Vantage

The motif is the simplest imaginable—a stretch of village houses seen from a low, frontal vantage with a shallow street or square in the foreground. By bringing the near plane so close and cropping the left façade abruptly, Matisse eliminates anecdote and perspective theatrics. The viewer stands in heat and glare with no figure to mediate the scene. The choice of viewpoint forces the painting to depend on what happens between the large fields of color. A single chimney punctuates the roofline, low trees rise as dark wedges, and a small annex peeks from the far right, but these are supporting actors. The lead roles belong to the pale wall at left, the receding run of smaller façades, the expansive sky, and the open ground.

Composition and the Architecture of Planes

Compositionally the painting is a game of balances. The blocky wall at left is a vertical weight planted near the edge, a decision that modernizes the framing and creates instant tension with the vastness of sky. The run of receding houses forms an oblique counterforce, sliding diagonally toward a darker screen of trees. The ground is a broad, low-angled wedge that pulls the eye inward while remaining subordinated to the upright façade. The sky, filling more than half the canvas, is the great horizontal counterweight, painted as a living field rather than a neutral emptiness. With so few elements, the composition is both readable and elastic; it invites attention to the play of edges and temperatures across the whole.

Color Architecture and the Working Ground

Perhaps the most striking feature is the sienna ground that breathes through almost everywhere. Matisse lets this warm undercolor function like the key of the painting. It warms the cool greens of the façades, it undergirds the pinks and blues of the sky, and it unifies ground and buildings so they seem struck by the same sun. The principal hue families are straightforward: pale celadon and cream for the walls, viridian-tinged shadows at edges and eaves, cobalt and ultramarine scumbles in the sky softened with white and rose, and turquoise notes dragging across the earth as reflective cools. Because the palette is limited and relational, each plane takes authority from its neighbors. The pale left wall reads as sunlit not because it is “white” but because it stands against a sky that has been pitched bluer and a ground that has been allowed to remain warmly exposed.

Light and Weather

The hour feels like late afternoon when light spreads laterally and the ochres of the street flare. There are no theatrical cast shadows; instead, temperature shifts do the work. Where the left façade approaches the sky it cools slightly; where the street plane tilts toward the viewer it warms and grows more saturated; where the houses recede, cool greens and bluish notes creep into their faces, recalling the effect of atmospheric perspective in architecture. The sky’s scumbles of cobalt and rose do not depict particular clouds so much as the sensation of wind-broken light. In this way the weather is present not as event but as condition.

Brushwork and Impasto

Matisse writes each substance with a different touch. The broad faces of the houses are laid with flatter, more opaque strokes that give volume without fuss. Along the edges—rooflines, wall joins—strokes remain visible and overlap, letting the sienna ground knit parts together. Trees and darker interstices are packed with denser, shorter touches, which resist glare and hold the central band in place. The sky is the freest: long, fast strokes and transparent drags pull blue across the warm ground so that the air shimmers. The paint’s physical relief is small but insistent, catching real light and contributing to the sensation of heat.

Drawing by Abutment

One of the painting’s modern virtues is the refusal of hard contour. The left wall is not ringed by a line; it is made by a creamy plane set against blue and sienna. The roof’s angle exists because a cool edge meets a warmer sky. Even the chimney is a block of color pressed against another block, its identity produced by value relationships rather than outline. This “drawing by abutment” keeps every part of the picture under the same illumination and gives Matisse fine control of spatial emphasis. A slightest warming of a junction brings it forward; a cooling or thinning lets it recede.

Space and Depth Without Linear Plot

The sense of depth is built from plane interactions rather than strict perspective. The giant left wall occupies the picture by sheer scale; the diminishing sequence of façades recedes not because the lines converge but because the colors cool and the strokes grow smaller. The ground advances with warm, thin scrapes that allow sienna to blaze; the sky backs up with blue scumbles that subdue that blaze. The outcome is shallow yet convincing space—exactly the modern depth appropriate to a street under high sun.

The Sky as Protagonist

It is tempting to treat the sky as backdrop, but here it acts as an equal protagonist. Matisse’s blue is not one note; it modulates through cobalt, ultramarine, and gray-blue, with rose and white thrown across it in veils. These strokes are not passive. They push and pull the silhouette of the buildings, carving and softening edges and giving the masonry a sense of being pressed upon by weather. The sky’s mobility keeps the heavy wall from deadening. It is the picture’s breath.

The Ground as Stage

The ochre ground is a stage that explains everything else. Scumbles of turquoise and pale green graze across it like reflected sky, persuading the viewer that the earth is open and sunstruck. Occasional darker scrapes and stains break the area so it does not become a blank floor. Because Matisse allows the ground to remain visibly underpainted in places, it binds building and sky and supplies the painting with a low, constant warmth.

Psychological Temperature and the Sense of Place

Although there is no anecdote—no figures, signage, or windows detailed—the painting conveys a strong mood. It is a day when heat presses, when stucco absorbs and radiates light, when the air seems to vibrate. The reductive geometry of the houses suggests sturdiness and quiet, a small settlement paused in mid-afternoon. The chromatic pitch—sienna against blue, celadon against rose—creates a psychological pitch as well: relaxed but alert, calm with a faint charge of weather. Matisse does not report a picturesque street; he offers the sensation of standing there.

Dialogue with Influences

“Houses” speaks to several neighbors without echoing them. From Cézanne Matisse draws the conviction that large planes can carry a composition and that color spots should build volume. From the Neo-Impressionists he adapts the idea that adjacency of hues can make a surface vibrate, though he rejects mechanical divisionism; his strokes remain responsive to the plane they describe. From Van Gogh’s southern canvases he inherits the belief that sky and wall can be equals, but he restrains agitation and favors equilibrium. The result is not derivative but assimilated: lessons filtered through a temperament seeking clarity.

Foreshadowing Fauvism

If one intensified the celadons to sharper greens, drove the ochres toward cadmium, and cleaned the blues to purer cobalt, the painting would sit comfortably among the Fauvist pictures of 1905. The structure is already in place: big, unconfused shapes; edges made by color meetings; whites treated as living tints; shadows chromatic rather than brown. “Houses” demonstrates that Matisse’s later audacity did not spring from caprice but from the discipline of working out a color architecture that could bear an increase in saturation without collapsing.

Materiality and the Breath of the Canvas

The visible ground is not just a color; it is a material fact. Where paint is thin, the weave of the canvas participates, catching light differently from the denser sky scumbles and the more opaque wall planes. This alternation of thin and thick, absorbent and reflective, is one reason the surface feels alive even when the motif is quiet. It also explains why the painting ages well: the variety of layers resists monotony and preserves the sensation of the painter’s hand.

How to Look Closely

Begin at the left façade and notice how its “white” is really a compound of cream, pale green, and gray, with tiny streaks of rose near the base where ground shows through. Follow the roofline where a single, cooler stroke at the eave is enough to set the plane turning. Move along the diagonal row of houses and see how each segment shifts temperature slightly, cooling as it recedes and then warming again near a tree. Rise into the sky and read the blue field not as one color but as a cloud of adjacent blues, with the warm ground breathing through to keep the air luminous. Drop to the foreground and watch turquoise skitter across ochre like reflections off stone. Step back and let the picture resolve into three commanding zones—ground, architecture, sky—held together by the sienna undertone. The longer you look, the more the scene becomes a set of calibrated intervals rather than a list of things.

Why the Simplification Matters

Matisse’s reductions are not shorthand; they are ethics. By choosing to say less—no windows counted, no bricks, no signage—he frees the painting to concentrate on the relations that make a place feel real: the pressure of sky on wall, the warmth of earth, the measured cooling of distance. This approach respects the viewer’s eye, which naturally reads the world by such relations. It also opens the path to later experiments in which color fields will shoulder even more responsibility while remaining legible and persuasive.

Place in the Oeuvre

Within the production of 1898, “Houses” forms a trio with “House in Toulouse” and several Corsican landscapes. Together they show Matisse testing the same grammar across subjects—urban façade, coastline, village street—and finding it robust. The painting thus occupies a crucial rung in the ladder from post-Impressionist observation to the radical clarity of Fauvism. It is a small but decisive proof that the world can be rebuilt with color planes and still keep its weight, its air, and its light.

Conclusion

“Houses” embodies a simple but profound claim: a picture can be constructed from a handful of colored planes laid over a living ground, and if the intervals between those planes are exact, the result will feel truer than a catalog of details. Matisse balances a pale block of wall against an oceanic sky, lets sienna hum through blues and greens, and trusts edges made by contact rather than line. In doing so he makes a village corner seem both solid and weightless, sun-struck and breathable. The canvas is quiet, but it contains the future; within these modest houses lies the blueprint for the unshakable color architecture that would soon define his art.