Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

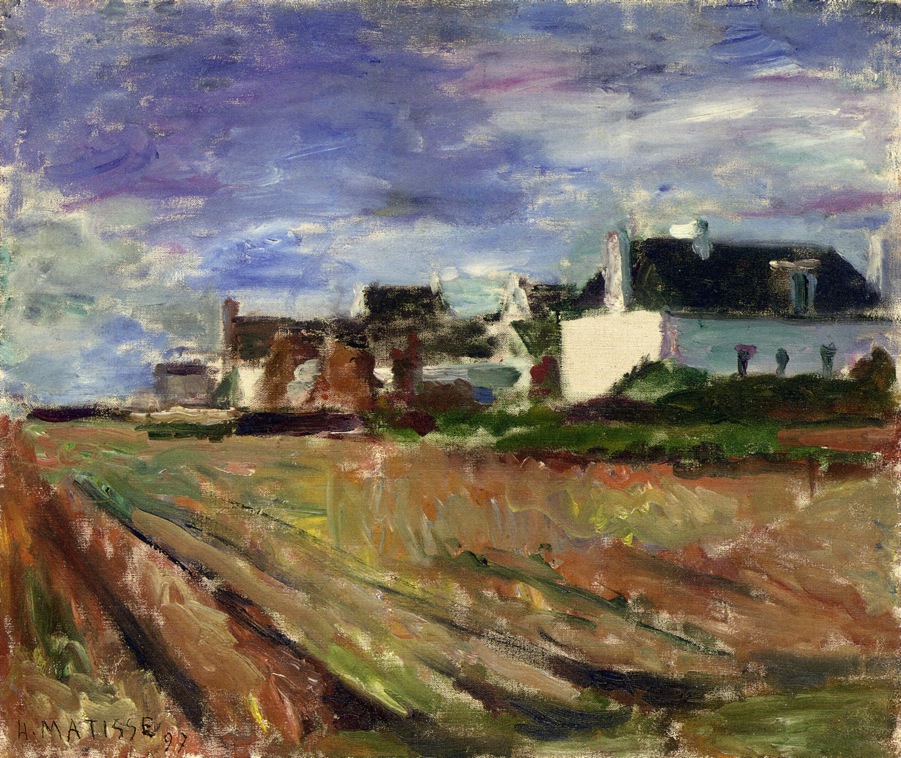

“Farms in Brittany, Belle Île” shows Henri Matisse in 1897 standing at the edge of cultivated ground and turning a strip of houses and a weathered sky into a disciplined arrangement of planes, temperatures, and strokes. A low band of farm buildings with dark roofs and bright gables sits across the horizon. In front of it the earth opens in long, furrowed ribbons that sweep diagonally from the lower left toward the middle distance. Above everything, a sky of blue, lilac, and milky white churns without theatrics, its broken light pressing gently on the land. The subject is simple—fields and farms—but the painting is alive with structural decisions: the way warm and cool colors lock together, the way edges arrive from abutting tones rather than drawn outlines, and the way the broad field of earth is kept mobile through directional brushwork. What we see is not a picturesque postcard; it is a working landscape translated into the grammar that would sustain Matisse’s later breakthroughs.

Historical Context: Brittany as a Workshop for Reinvention

The summers of 1896–1897 on Belle-Île and in rural Brittany marked a turning point for Matisse. After rigorous academic training and early tonal still lifes, he went to the Atlantic coast to paint directly from the motif. The island’s hard geology, low houses, and ocean-bright light forced simplification. He began to trust that a painting could stand on a few large relations—mass against mass, warm against cool, long directional forces against small cross rhythms—without recourse to polished detail. “Farms in Brittany, Belle Île” belongs to this second summer, when his palette lifted, whites became active, and brushwork settled into a rhythm that recorded both seeing and weather. It is country subject matter pressed into modern form.

The Motif and the Deliberate Viewpoint

The motif is the everyday meeting of field and village. Matisse positions himself low in the furrows, slightly to the left of the scene’s central axis. That vantage turns the foreground into a fan of earth-toned pathways leading the eye toward the horizontal band of buildings. The farms are not individualized; they register as a broken, bright strip of gables, chimneys, and rooflines. A single near-white facade sits almost center-right like a sunlit block, while darker roofs and shadowed walls stitch the band together. The viewpoint is tactical: it gives the painting a clear foreground engine, a compact architectural middle, and a high, expansive sky.

Composition: Diagonal Furrows and a Horizontal Village

The picture is built on the interplay of a dominant diagonal and a stabilizing horizontal. The furrows sweep from the lower left corner up into the center, their slant echoed by the brushwork of grasses and the color bands running along them. This diagonal has multiple jobs: it pulls the viewer into depth, it breaks an otherwise flat field into rhythmic paths, and it energizes the surface without relying on narrative. Against that movement, the village runs as a horizontal counterweight. The thin line of houses keeps the composition from spinning and anchors the eye before it lifts into the sky. A narrow dark strip of hedgerow just before the buildings works like a hinge between land and architecture. Everything is kept taut but balanced: motion below, stability at the horizon, breadth above.

Color Architecture: Warm Earth, Cool Sky, and Living Whites

Color carries the structure. The foreground earth is painted in a tempered range of raw sienna, burnt umber, brick red, and dusty greens that braid together where furrows catch or lose light. Those warms are opposed by the cool upper half—the sky’s violets and blues thinned with white, scumbled so the ground breathes through. Between them sits the village, where white is not neutral: gables and walls are mixtures of pearl, cream, and pale blue; roofs settle into green-black and indigo; small rose and rust notes warm doorways and shadowed creases. The most intense white, the blocky facade near center-right, acts like a beacon. It is the brightest note in the painting, and by calibrating the rest of the whites to that pitch, Matisse makes the village feel truly sunstruck without using theatrical contrast.

Light and Weather: High Atlantic Brightness

The light is that cool, maritime brightness typical of Brittany—sun filtered through scudding cloud. It cools shadows, diffuses highlight, and sets a general high key without blinding glare. Matisse renders the sky with broad scrapes and feathery strokes that allow the canvas’s warmth to show through, giving a sense of air in motion. On the ground, value steps are moderate: the earth warms where ridges turn to the light and cools in the troughs, but a single weather binds them. The buildings catch this light asymmetrically—one gable blazing, a neighboring wall in soft shadow—so that the band of architecture reads as a chain of volumes, not a flat silhouette.

Brushwork and the Tactile Logic of Surfaces

Each zone receives a distinct touch. In the field, long, oblique strokes travel with the furrows, interleaved with shorter, dragged notes that imitate the scuffed texture of soil and grass. The village is handled more compactly: roofs are laid with thicker, blocky touches; gables turn with small, cool accents; chimneys are flicked on with confident dabs. The sky is the loosest, where paint is thinned and scumbled, allowing the weave beneath to participate. This orchestration of touch is descriptive and structural at once—earth feels springy and worked, buildings feel dense and still, air feels broad and unsettled.

Drawing by Abutment: Edges as Contact Instead of Outline

A striking modern trait of this canvas is how rarely Matisse uses a hard contour. Forms exist because neighboring planes meet at convincing values and temperatures. The top edge of a roof is a seam where a dark, cool field abuts a pale, violet-blue sky; the edge of a white wall occurs because a cooler white comes up against a warmer shadow; furrow ridges appear as slender highlights shared between two earth tones. This method keeps the image unified in one light and gives the painter freedom to adjust color for structural reasons—warming a wall to bring it forward, cooling a shadow to settle it—without being trapped by linear boundaries.

Space and Depth Without a Diagram

Depth is built from stacked planes and calibrated color intervals. The near ground is most saturated and textured; mid-ground furrows thin and cool; the hedgerow flattens into a dark band like a horizon base note; the buildings are lighter and clearer; and the sky thins further as it rises. Perspective lines are implied by the furrows but not measured with ruler precision. The eye accepts recession because the steps are consistent and because brush scale diminishes naturally with distance. A few small verticals—chimneys and treelets—punctuate the village band and give scale to the whole, reminding us that these are human structures in a large field.

The White Facade as Pivotal Form

Near the center-right stands a broad, sunstruck wall rendered in thick, almost unmodulated light. It is the painting’s keystone. Against the cool roof beside it and the darker strip below, this plane sets the pitch for every other white in the picture, from pale gables to sky tints. It also solves a compositional problem: by providing a bright pause in the village band, it prevents the strip of architecture from reading as a single, monotonous silhouette. The small cool strokes that nibble at its edges—chimney shadow, roof return—keep it a volume in light rather than a blank rectangle.

The Psychology of Color and the Mood of Use

The canvas does not chase rustic charm; it feels like a place of work. The earth’s reds suggest turned soil, the deep greens hint at hedges holding fields against wind, the roofs are heavy and weatherproof, and the sky is busy with moving light. The palette’s restraint amplifies this mood. Rather than showy accents, there are measured exchanges: warm furrow against cool trough, bright gable against dark roof, lavender cloud against pale blue. The scene conveys industrious calm—a day when weather allows tasks to continue and the farms hold steady under a wide, shifting sky.

Dialogue with Influences: From Cézanne’s Construction to Breton Simplification

Matisse’s approach here speaks to two powerful influences. From Cézanne he takes the insistence that forms must sit stably in the world—houses as blocks, roofs as planes, fields as large tilting surfaces. From Brittany’s late-century painters he takes the courage to simplify, to permit large color fields to stand for light and air, and to crop the world decisively. Yet the painting is unmistakably his. He neither diagrams like Cézanne nor flattens like the Nabis; instead, he uses color relations to negotiate depth in a way that will soon support far more saturated harmonies.

The Role of the Ground and the Breath of the Canvas

A warm undertone peeks through in many places, especially near the sky’s edges and in thinner passages of the fields. Matisse lets this ground act as a common thread that warms the whole and prevents the cools from going chalky. He alternates areas of thin, breathable paint with thicker, assertive notes. Thick paint claims attention—on the white facade, in dark roof masses—while thin scumbles let a sense of air persist. The painting’s physical skin thus echoes its subject: hard planes of building against broad stretches of weather and soil.

Rhythm and Movement Across the Surface

Even without figures, the painting moves. The furrows deliver a steady beat across the lower half, their oblique rhythm accelerating the eye. The village band provides a slower counter-tempo, punctuated by chimneys and gables like notes on a staff. The sky’s brushwork drifts at yet another pace, lateral and relaxed, a visible breeze. Because color is relational rather than flamboyant, these rhythms harmonize rather than compete. The result is a visual pacing that feels like walking the field, pausing at the hedgerow, and scanning the roofs beneath a living sky.

Foreshadowing of Later Matisse

Though subdued compared to the high-chroma canvases of 1905, “Farms in Brittany, Belle Île” contains the logic that would make that leap possible. Whites are active and varied, shadows are chromatic rather than gray, edges are seams between colors, and a few large shapes govern many small incidents. Intensify the palette and the picture would still hold, because its scaffolding—diagonal land, horizontal village, broad breathing sky—remains firm. The painting proves that Matisse’s later audacity rests on earlier discipline.

Technique and the Order of Decisions

The sequence of making remains legible. A toned ground sets a warm key. Large planes are blocked early: diagonal field, dark hedgerow, band of buildings, broad sky. Over these, directional strokes describe use and texture—furrow rises, roof facets, drifting cloud. Whites are tuned late to fix the key and set the hierarchy of light. Final accents, like the small vertical chimneys and the edges of the white facade, are placed to calibrate depth and give scale. Nothing feels overworked; the canvas preserves the momentum of decisions made on site.

How to Look at the Painting Today

Begin at the lower left corner and follow the long strokes of the furrows as they braid warm earth with cool greens. Notice how these strokes thin and cool as they recede. Pause at the hedgerow’s dark strip and sense how it locks the land to the village. Move along the band of houses and watch how whites change—cream, pearl, bluish—depending on their neighbors. Test the rooflines where cool darks bite into the sky. Finally, rest in the upper half and read the sky’s thinned blues and lilacs as a wide, moving field. Step back and let the whole resolve into three great actors—earth, village, air—held in a poised balance.

Conclusion

“Farms in Brittany, Belle Île” is a quietly confident statement about how a painting can carry the truth of a place with a limited palette, a few decisive shapes, and strokes that respect both structure and weather. A diagonal of worked ground meets a horizontal of houses; warm earth answers cool sky; living whites knit architecture into air. The image convinces without anecdote because its relations are exact. From this clarity Matisse would soon claim the freedom to raise chroma and simplify further, knowing the painting would still stand. Here, in a Breton field under a marine sky, that grammar is already fluent.