Image source: wikiart.org

A Coastal Turning Point In Matisse’s Eye

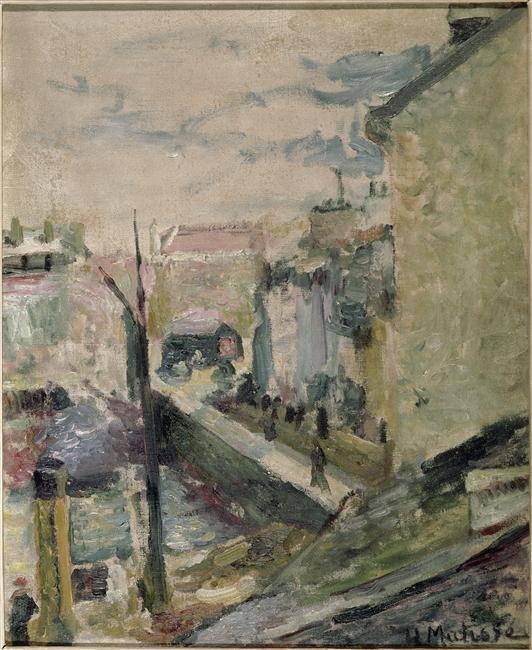

Henri Matisse’s “Belle Ile” (1896) captures a Breton harbor scene at the moment his vision was shifting from academic earthiness to a more liberated, light-driven language. Painted after he traveled to Belle-Île-en-Mer off the southern coast of Brittany, the canvas records more than a place. It records an awakening. The island’s weather, water, and stone unleash a new responsiveness in Matisse’s brush, and the city-like structure of quays, bridge, and walls gives him a scaffolding on which to test bolder mark-making. What you see is not a polished studio picture but a fast, wind-salted notation of things learned outdoors: how water eats light, how stone exhales color, how air turns forms porous. The painting stands at the threshold between his sober student years and the chromatic audacity he would declare a decade later.

The View From A Tilted Perch

The composition begins with a risky vantage. Matisse places us high on a bank or rooftop, peering down a steep diagonal into a canal or narrow harbor that runs toward an arched bridge. The right edge is dominated by the plane of a wall or roof that shears across the picture like a cliff, while the lower left is punctuated by pilings and the dark seam of a quay. These oblique surfaces act like rails; they funnel the eye into the picture’s throat, where a shadowed tunnel of the bridge intensifies depth. The move is architectural but kinetic: it makes the space feel navigated rather than merely observed. Even a simple trunk of a tree or mooring pole becomes a visual hinge, breaking the sky’s softness with a vertical insistence.

The Pulse Of The Brush

Surface carries the weather. Strokes are short and quick, each a gust of air rather than a polished contour. Matisse drags diluted pigment in places so the canvas peeks through like dry plaster, then rams thick, buttery touches into the water where light shatters. The bridge’s arch is not fully drawn; it emerges from a swarm of strokes that coalesce just enough to be legible. Buildings are built with strokes laid side by side like masonry; water is written in commas and flecks. That insistence on facture—on the stroke as both description and event—will become a lifelong principle: painting is not an image that disguises its making; it is a record of looking that stays visible.

A Palette Tempered By Sea Air

The color key is cool and reticent: slate blues, sea-glass greens, grayed mauves, chalky creams, and the occasional bruise of umber. It is a coastal tonality, humid and mineral. Within that restraint, small temperature shifts do the heavy lifting. Pale rose meets gray to warm the far roofs; green digs into blue to deepen the water’s shadow; a whisper of sulfurous yellow leaks through the clouds and tinges a wall. Because saturation is low, value and temperature organize the scene more than hue. That hierarchy is crucial to understanding Matisse’s later radical color: before he emancipates color, he learns how to make color obey structure.

Water As The Engine Of Space

The water isn’t a passive mirror; it is the picture’s engine. Its broken highlight pulls the gaze down the diagonal canal, and its darker eddies carve a path for recession. Matisse treats the water’s surface as a zone where the sky’s light and the stone’s shadow negotiate. Look at the criss-cross of laid strokes: horizontal pulls that state the plane, interrupted by small vertical darts that suggest the chop of breeze or the wink of reflected pilings. That weave gives the water a physicality that echoes the weave of the canvas itself. Paint embodies place; support and scene rhyme.

Architecture As Rhythm, Not Diagram

Buildings and parapets read as masses rather than drafted elevations. Matisse locks them with crisp, straight thrusts, then dissolves edges where air softens the view. The vertical wall on the right is treated like a single abstract plane tipped toward us, its inner contour eaten by atmosphere. The bridge is present as a value block whose arch is the one crisp cavity in a room of vapor. This priority of masses over anatomy puts Matisse in dialogue with the structural clarity of Cézanne, yet his touch is looser, more improvisatory. He wants the picture to breathe, not ossify.

The Human Scale Amid Stone And Sky

Minuscule dark figures move along the quay and up the ramp toward the bridge. They are no more than flicks of the brush, but they provide a unit of measure. With them in place, the facades swell, the wall’s drop becomes perilous, and the water chills. Their anonymity is intentional; they are scale bars rather than portraits, a tool to keep the landscape honest. By refusing narrative, Matisse commits the picture to perception itself as drama.

Weather As Motif

This is a day of high cloud and shifting light. The sky is a tissue of wet grays with veins of pale blue. Light is neither golden nor theatrical; it is milked through the atmosphere and pooled on stone. That weather is not an afterthought; it’s the motif. The whole painting answers the question: how does a place feel when its edges are softened by marine air? Matisse’s answer is psychological as much as optical: the looseness of the marks registers restlessness, the cool tonality quiets the scene, and the hazed distance makes time slow.

Belle-Île In The Painter’s Biography

The trip to Belle-Île sits at a crux in Matisse’s formation. On Brittany’s coast he painted directly from the motif in tough, salty conditions. The island was already a magnet for artists drawn to its churning seas and fissured rock; Monet had made a celebrated series there a decade earlier. For Matisse, the island offered a school without walls. He studied not the heroic storm but the grammar of light as it mapped itself across stone and water. In that sense, “Belle Ile” is less a postcard than a workbook page—one of the sheets where he discovers that liberation comes by attending to what is in front of you with ruthless honesty.

Between Academic Brown And Fauve Flame

Seen alongside his earlier studio pictures, this canvas loosens every joint. Edges are not diagrammed; shadows are not filled with bitumen; the sky is not a theatrical drop. It is the same painter who, a few years earlier, carefully modeled a figure in smoky tones—but he has started to trust the sensation of the moment. At the same time, the color is still tempered, the drawing latent rather than declarative. This is the bridge between the academic and the Fauve, and you feel him crossing it brushstroke by brushstroke.

Diagonals That Carry The Eye

The picture’s momentum lives in its diagonals. The roof at right dives toward the center, a dark toboggan that dumps us at the quay’s edge; the canal shoots leftward; the bridge’s parapet cuts back right; a bare pole rises like an exclamation; the sliver of road zigzags up toward the arch. Each angle counters another so the composition neither stalls nor spirals out. The sky’s long, low clouds reinforce the forward pull, like wind lines in a map. Matisse uses these vectors to choreograph perception: we don’t scan; we travel.

Drawing With The Brush

No linear underdrawing is visible. The brush itself draws as it describes. A single loaded stroke lays the edge of a wall; a dry drag states the parapet; a dab opens a window; a scrubbing motion grades a sky. That trust in the brush as a thinking tool explains why so many edges are “lost and found.” The eye completes what the hand suggests. Far from negligence, this economy is a form of generosity: the painter leaves space for the viewer’s vision to collaborate.

Matter Of Scale

The canvas is modest in size, and that intimacy shapes its rhetoric. We feel the painter’s arm reach, the time between loading the brush and laying the stroke, the quick returns to adjust a value. Monumentality would have turned the harbor into saga; smallness keeps it truthful. The image has the density of a plein-air note cribbed on the spot and only lightly corrected later. That immediacy is its charm and its authority.

Echoes And Departures

Traces of past and future jostle harmoniously. From the past: a tonal discipline learned from academic study, the weight of stone as a stable armature, the humble respect for everyday labor evident in the tiny figures. From the future: the tilt that will animate his interiors, the broken surface that will later acquire saturated color, the trust that color temperature alone can turn a plane. In the tension between those tendencies lies the painting’s particular vitality.

The Poetry Of Imperfection

Nothing is fully regularized here, and that is the point. The bridge is not centered; the wall lurches; the sky is scratched; the pilings tilt. Yet the composition holds. The roughness carries truth the way a handwritten note carries voice. Matisse is not after photographic fidelity; he is after the sensation of having been there. That sensation requires him to leave evidence of the time it took to see—the starts, revisions, and emphatic re-statements that still flicker on the surface.

How Light Describes Distance

Atmospheric perspective is a quiet protagonist. Distant roofs bleach; far walls soften; shadows lose contrast. The arch, though dark, is veiled by intervening air, so its darkness never becomes a hole. Matisse gauges these compressions deftly. Without resorting to hard linear perspective, he lets the atmosphere itself grade the space. It is a painter’s solution to a spatial problem: depth as a function of light rather than drafting.

A Guide For Looking

To read the painting fully, start with the big planes: the roof at right, the canal below, the band of buildings that cinch the middle distance, the pale, eventful sky. Let your eye pass under the bridge, then bounce back along the water’s glitter. Notice how the quayside figures, though minute, punctuate the rhythm like beats in a bar of music. Step close and count the kinds of strokes—fat, thin, dragged, dabbed—each a different note in the weather-chord. Step back and feel how all this resolves into a single sensation: a cool day by a Breton harbor seen from a precarious perch.

Why “Belle Ile” Matters

This painting matters because it bears witness to an artist becoming porous to the world. It shows that before Matisse could orchestrate violent harmonies of pure color, he learned to hear the quieter harmonies of grays and greens that the sea teaches. It demonstrates how a disciplined construction can host a free, responsive touch. And it offers a durable lesson for looking at his later work: beneath every blaze of Fauvist orange is the memory of a slate sky, a chalky wall, a canal that turns the world into increments of light.

From Island Air To Studio Fire

In the years after “Belle Ile,” Matisse’s palette would ignite, but the bones of this coastal picture remain. The oblique thrusts, the emphasis on mass over contour, the faith that paint can be both description and presence—all endure. Seeing the island through his 1896 eyes helps us read the later interiors, odalisques, and dance figures not as sudden breaks but as consequences of a long apprenticeship to light. That is the deeper story the canvas tells: a young artist learning to trust sensation—and, in trusting it, finding a path to invention.