Image source: wikiart.org

The Threshold Of A Career

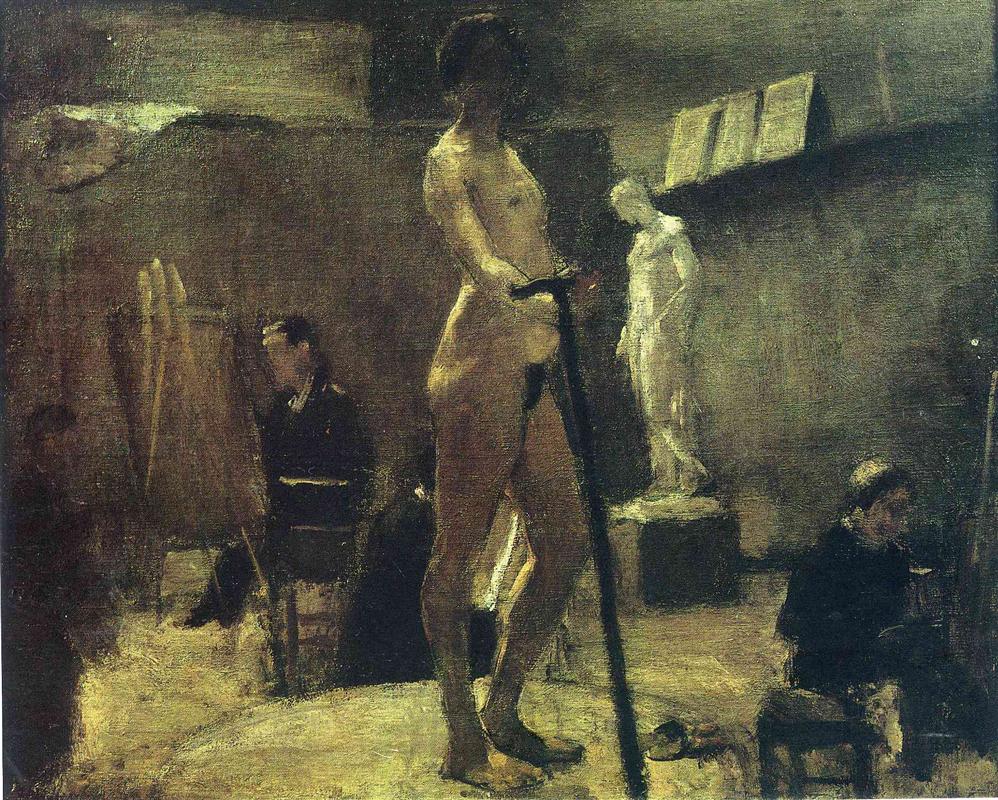

Henri Matisse’s “The Study of Gustave Moreau” (1895) drops us into an art school evening where the air is thick with charcoal, oil, and purpose. A nude model stands in cool light at the center, her vertical silhouette dividing the room as students hunch at their easels. To the rear, a plaster cast of a classical figure glows on a pedestal. Books or portfolios sag on a high shelf, and the floor reads like a pale ring of trampled dust where countless feet have ground chalk into the boards. The painting is at once documentary and introspective: a record of the atelier of Gustave Moreau—Matisse’s transformative teacher—and a meditation on the moment when seeing turns into art.

Inside Moreau’s Atelier: What We See

Matisse positions the model slightly off-center but makes her the axial pivot of the composition. She grips a long staff, the studio’s balancing rod, and her body catches the strongest light in the room. Around her, four zones sketch the studio’s ecosystem. At left, an easel rises like a ladder of golden slats; behind it, a student dissolves into dusk. In the back, the white plaster statue gleams with cold ideality, a ghost of the antique that students are tasked to measure themselves against. At right, a seated figure leans forward, intent and almost swallowed by shadow. The walls are a brownish fog; objects emerge from it only when the eye lingers. The subject is not portraiture but practice—the collective labor of learning to see.

Composition Organized By Axes And Orbits

The first structural decision is the vertical axis of the model and her staff. Matisse aligns the figure like a column that holds the room together, a living pillar whose warm flesh tones replace the chill of stone. Around that axis he builds orbits. The pale ellipse of trampled floor, the round top of the plaster pedestal, the looping arc of the easel’s legs, and the circular halo of light behind the model’s torso create a system of echoes that keeps our gaze circulating. The composition is a dialogue between straight drives and soft rings, between the rule of the vertical and the choreography of curves. It’s disciplined but never rigid—an order that breathes.

Value Over Hue: A Language Of Earth And Light

The palette is a low, earthy register: raw umbers, smoky greens, leaden grays, with flesh modeled in muted ochres and thin pinks. Against this tonality, small temperature shifts do enormous work. The model’s skin warms where lamplight touches the thigh and cools into gray on the shadowed ribs. The plaster cast carries a bluer white; the floor warms to straw near the easels; the distant wall recedes in greenish brown. Because hue is so restrained, value relationships take over. The painting is built like a fugue in grays where a single bright note—the gleam on a shoulder, the flare on the plaster cast—can re-key the whole scene. This discipline in value would become the scaffolding on which Matisse later hung his audacious color.

Facture That Makes Air Visible

Up close the surface is alive with changes of pressure and medium. Thin, scrubbed passages let the ground show through; thicker ridges catch actual light, turning highlights into three-dimensional events. Matisse scumbles smoky layers over the wall so it reads as breathable air, not a flat backdrop. He roughs in easels with swift, straight pulls, then softens them with a drag of the brush, as if dust lay on everything. Edges are “lost and found”: a calf dissolves where it sinks into gloom; a cheek is crisp where light rakes across it. This negotiation of edges is not stylistic garnish; it’s how the painting convinces you that bodies occupy space shared with you, a viewer standing just inside the door.

The Drama Of Light Sources

The room appears to be lit by a combination of high studio windows and localized lamps. Light falls from upper left, catching the model’s torso and shin, and rebounds off the chalky floor. Compare the warm notes on her nearer leg to the cool whites on the plaster cast: Matisse differentiates living flesh from plaster not by line but by temperature. The tallest easel throws a long bar of shadow; the student at right is swallowed into a pool of darkness that stresses his concentration. Because light is not uniform, it becomes the painting’s true protagonist, revealing and concealing with purposeful bias. The result is a visual hierarchy that quietly asserts what matters: the central act of looking.

Living Body Versus Classical Ideal

One of the most telling oppositions is the living nude and the plaster cast. The plaster’s blanched luminosity recalls the museum; the model’s warm tonality belongs to the here and now. Positioned in the same beam of light, they enact a debate central to Moreau’s pedagogy: learn from the antique, but do not copy it. The staff in the model’s hand has its own metaphorical weight. It is a practical prop, but it also reads like a measuring rod—an emblem of the student’s task to measure tradition against perception. That rod’s shadow doubles the vertical, tying the model (practice) to the statue (canon) and the student’s easel (work).

The Social Theater Of Learning

Matisse populates the room with students, but he erases their faces into general types. This anonymity universalizes the scene: we are in any atelier where people learn to translate sight into structure. The students’ postures—hunched, kneeling, intent—describe a choreography of attention. Everyone is oriented toward the model; the painting becomes a pinwheel with the human body at its hub. The collective quiet is palpable. You can almost hear the squeak of a stool leg, the scratch of charcoal, the solemn exhale after a measured line. The painting respects that ritual: it is a votive to concentration.

Moreau’s Pedagogy As Subject

Gustave Moreau, a symbolist renowned for luxuriant color and mythic imagery, surprised many by practicing a liberal, almost modern teaching method. He urged students to find their way rather than adopt his style. The painting honors that spirit by refusing bombast. Instead of myth, we get method; instead of spectacle, process. The tonal range, the careful grouping of values, the seriousness of the studio environment—these form a visual essay on Moreau’s mantra that individuality rests on solid craft. Matisse absorbs the lesson without imitation: he is already choosing what to omit, which relationships to emphasize, and how to make atmosphere carry meaning.

Early Realism, Future Fauvism

The canvas belongs to Matisse’s formative, “brown” years, when he studied intensively from the figure and from still life. Yet it contains seeds of the painter to come. The centrality of the nude anticipates his lifelong fascination with the human body as a vessel for rhythm and emotion. The simplification of big shapes—floor, wall, figure—prefigures the planes of his Fauvist interiors. Even in this restricted palette, color is structurally deployed: a warm reflex on skin locks the composition, just as a slab of viridian would later anchor a Fauvist still life. The painting whispers what later canvases will shout.

Space As Stage And Workshop

Matisse’s perspective is modestly deep but deliberately shallow near the back wall, compressing distance so that background figures and objects feel within arm’s reach. The floor reads like a circular dais, a stage on which training plays out. The near darkness at the picture’s edges frames the action and keeps the viewer’s attention inside the ring. The high shelf with portfolios tilts toward us, its precarious angle a reminder that the studio is a working place, full of temporary solutions and stacked intentions. It’s not a grand salon; it’s a laboratory.

The Poetics Of Materials

Part of the painting’s spell is the way it renders the things of art-making: the grain of the easel, the chalk haze on the floor, the absorbent wool of the model’s rug, the cold plaster glow of the cast. These are not incidental props. They deliver the tactile reality in which artistic knowledge is built. The student at right sits on a humble, square stool, an echo of the easel’s verticals; the rubbery heel of the model’s shoe peeks out near her foot, a sly admission of the practical accommodations that coexist with the high rhetoric of the nude. By taking care with such details, Matisse claims dignity for the studio’s ordinary theater.

Atmosphere As Emotion

Though the image is outwardly neutral, it carries emotion as weather. The brown-green vapor of the room suggests both fatigue and focus; the near silence of the palette feels monastic. The strongest expressive note is the model’s stance, upright yet relaxed, poised but human—an embodiment of vulnerability offered to the collective gaze. The students’ immersion reads as devotion. Without resorting to melodrama, Matisse finds feeling in the temperature of the room and the slowness of time, like a chapel where the sacrament is looking.

A Conversation With Degas, Fantin-Latour, And Whistler

Art-historically, the painting touches several strands. Degas’ rehearsal rooms and laundries showed how labor and looking can be staged without anecdote; Fantin-Latour’s studio group portraits explored the fellowship of artists; Whistler’s tonal harmonies proved that a restricted gamut could carry atmosphere. Matisse does not mimic these precursors, but his solution resonates with them. He accepts Degas’ insistence on structure, borrows Fantin-Latour’s respect for professional camaraderie, and adapts Whistler’s tonalism to a more tactile, physical surface. The result feels specific to Paris in the 1890s yet unbound by any single precedent.

Time Of Day And The Rhythm Of Work

The cool top light indicates afternoon fading toward evening—a typical schedule for academies, where models pose in long, measured sessions. The arc of brightness on the floor’s left edge implies a window just out of frame, while the warmer lumens on the model’s shin may belong to a supplemental lamp. That mutual presence of natural and artificial light deepens the image’s meaning: learning to see is both a question of nature (what the world offers) and culture (what the studio supplies). Matisse makes the two sources harmonize without erasing their difference.

The Ethics Of Restraint

One of the painting’s quiet triumphs is what it refuses to do. There is no theatrical spotlighting, no sentimental interlude, no caricature of a professor. Even Gustave Moreau is absent, present only in the discipline of the room bearing his name. This restraint has an ethical dimension. The young painter prioritizes relationships—of value, temperature, and mass—over virtuoso display. That choice is not timidity; it is clarity. It expresses respect for the model, for the work, and for the viewer’s intelligence. It also marks Matisse’s enduring belief that simple structures can sustain complex feeling.

Looking Forward From 1895

Within a decade, Matisse would explode into color with “Luxe, Calme et Volupté,” “Woman with a Hat,” and the blazing orchestras of Collioure. Yet the discipline of this studio scene survives in those works: large structural divisions, decisive edges, and a trust in the organizing power of light. The atelier’s circle of floor becomes, later, the circular dance; the vertical of the model becomes the verticals of windows, instruments, and standing figures; the dialogue between warm and cool grays becomes the clash—then harmony—of pure complements. “The Study of Gustave Moreau” is less a detour than a root.

How To Look At The Painting Today

Stand back and take the structure first: the vertical of the model, the oval floor, the dark envelope of walls. Step closer and watch how edges soften into air; notice how the plaster’s blue-white differs from the model’s straw-white; track the way a single pale mark on the floor lights the lower left quadrant. Let your eye move from the living body to the statue and back; feel how the painting toggles between present and canon, instruction and invention. Then imagine the hour after the session ends, when students stretch, brushes clink in turpentine jars, and the model puts on a robe. The painting hums with that fatigue and fulfillment.

Why This Early Work Matters

This canvas matters because it documents the conditions under which one of the twentieth century’s most original painters learned his craft. It matters because it shows that Matisse’s radical color grew from sober attention to value and form. It matters because it dignifies the studio—the place where repetition, measurement, and patience incubate originality. And it matters because it transforms a dim room into an image of collective aspiration, holding in suspension the classical past, the labor of the present, and a future that—though Matisse could not yet know it—would blaze with unexpected light.