Image source: wikiart.org

Setting The Scene: A Quiet Laboratory Of Looking

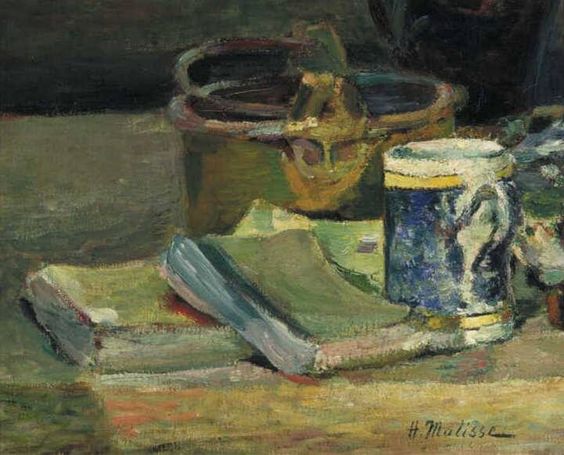

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Books” (1895) is an intimate cabinet of quiet things: a short stack of green paperbacks, a blue-and-white stoneware mug, and a brass pot with a hinged handle, all gathered on a modest tabletop. The painting’s scale is domestic rather than grand, yet its ambitions are large. In this compact arrangement Matisse tests how light clings to different surfaces, how color temperatures set moods, and how a few shapes can conjure an entire room. Long before the blazing chroma of his Fauvist canvases, he was learning to make small tonal shifts speak volumes. The image feels like an interior whisper—concentrated, thoughtful, and serious about the business of seeing.

Where Matisse Stood In 1895

The mid-1890s were a forming period for Matisse. Still in his twenties, he had committed to rigorous academic training but was already edging toward the liberations of modern painting. He copied old masters, absorbed the tonal discipline of the studio, and studied the way Impressionists let light fracture color. “Still Life with Books” belongs to that crucible. It retains academic virtues—care for structure, a sober palette, faithful attention to light—yet it hints at future freedoms. The motif itself is telling. Books and a mug suggest the painter’s own workday: long hours of reading, sketching, and looking, accompanied by the everyday props of concentration. Rather than staging a showy tableau, Matisse chooses the humble companions of study and turns them into a proving ground.

Composition As Architecture

The composition is a lesson in how a few forms can organize space. Three principal masses anchor the design: the horizontal wedge of books in the foreground, the cylindrical mug to the right, and the rounded brass container behind them. Together they make a shallow triangle that points inward from the lower left and stabilizes the picture against the darker background. The tabletop runs across the lower third as a pale plane, while the rear wall—kept in compressed, mossy shadow—pushes the objects gently forward. Matisse carves a channel of air between the books and the mug, and another between the mug and the pot, giving each object room to declare its silhouette. The effect is architectural but not stiff: edges soften where forms meet light, and the triangle flexes in response to the swirl of brushwork.

The Stagecraft Of Light

Light falls from the left, travels across the table, and blooms most strongly on the books’ paper edges and the mug’s rim. The brass pot grips light differently: instead of a sharp highlight, it drinks in a warm glow that rises and falls across its hammered skin. These variations are the true subject of the painting. Matisse studies how paper’s chalky matte breaks the beam, how glazed stoneware returns it in cool flashes, and how tarnished metal traps it in mellow amber. Notice the mug’s upper edge: a thin, decisive ring of pale tone defines the cylinder more convincingly than any contour line. On the books, a sliver of near-white along the fore-edge tells us the pages are many and softly irregular. The painter makes illumination the primary narrator; drawing and contour quietly assist.

A Palette Tempered And Warm

The color range is deliberately restrained: olive and bottle greens in the bindings, ochres and bronzes in the pot, dusty blues in the mug, and a spectrum of earth tones holding everything together. Rather than dazzling us with hue, Matisse explores the conversation between warms and cools. The blue of the mug leans cool against the pot’s honeyed metal; the green of the foremost book drifts toward blue in shadow and toward yellow under the light. These relationships create an atmosphere of late afternoon calm. We sense a room where work pauses—a book set down mid-chapter, a mug with the last mouthful cooling. The palette is not yet the riotous chord of Fauvism, but the discipline here—matching value precisely while letting color breathe—will underwrite the boldness to come.

The Touch Of The Brush

Matisse’s brush is responsive to material. On the books, he lays down thick, short strokes that follow the slap and warp of paper covers; along the fore-edges he feathers lighter pigment to suggest frayed pages. On the mug he turns to smoother, curving strokes that track the cylinder and emphasize glaze. For the brass he uses broader, fused marks, scumbling thin lights over darker underlayers so the metal seems to retain old light within it. In several places he leaves “breathing gaps” where a previous layer peeks out—muted reds and browns that enliven the surface without calling attention to themselves. This active surface prevents the low-key palette from going dead; the eye keeps finding new inflections, as if the paint itself were thinking.

Edges That Carry Meaning

Edge handling in this picture is a craft all its own. The lip of the mug, the corner of the book nearest us, and the hinged clasp of the pot receive the crispest accents, inviting the eye to land and then wander. Other edges—where the books’ shadows meet the tabletop, or where the far side of the pot melts into the wall—are softened almost to disappearance. These transitions describe space more persuasively than perspective lines would. They also set a rhythm: crisp, soft, crisp, soft—a pulse that keeps the gaze attentive. Matisse uses edges as syntax, pausing and accelerating the sentence of the image.

Surface, Weight, And The Poetics Of Matter

One could almost inventory the room by touch. The books look heavy in the hand, their spines softened by use; the mug reads as cool and slightly slick; the pot promises the warm resistance of metal. Matisse treats these sensations as content. The painting is not about objects as symbols alone; it is about matter as experience. That ethos—recognizing the dignity of ordinary substances—is part of what will make Matisse such a humane painter of interiors. Long after 1895 he will still be modeling the friction of a tabletop, the flutter of a curtain, the resistance of a patterned robe. Here we see the ethic begin.

Symbolic Undertones: Books, Mug, And Pot

Even in a sober study, meanings accumulate. Books are emblems of inwardness, learning, and the patient gathering of knowledge. In fin-de-siècle Paris, they also marked a newly portable education: cheap paperbacks, often in green wrappers, circulated ideas among students and artists. The mug, humble and sturdy, stands for the daily economy of work—the studio companion that makes hours pass. The brass pot, with its clasp and hinged handle, introduces craft at a different scale: the container of liquids, perhaps of pigments, perhaps of household necessities. Together they speak of a life organized around study and making. There is no luxury here, only the comfort of tools well used.

A Conversation With Tradition

“Still Life with Books” nods to several lineages. From Chardin it borrows the gravity granted to ordinary things and the respect for tonal atmosphere. From Dutch still life it inherits the pleasure of depicting different materials—the joy of switching brushes as one moves from paper to metal to glaze. From Cézanne, whose example Matisse would increasingly weigh, it takes the idea that color patches can construct form as powerfully as line. Yet the painting is not a pastiche. The objects are compacted, the viewpoint low, the background simplified to a dark plane—decisions that strip away anecdote and keep attention on the central problem: how light and color build presence.

The Space Between Objects

The intervals matter as much as the things themselves. Consider the slender wedge of tabletop that peeks between the books and the mug; it is only a hand’s breadth, but it deepens the space and gives breathing room to both forms. The shadow cast by the mug cascades leftward, gently touching the spines of the books; this contact creates a visual handshake, a subtle union of the cluster. Behind the pot, the wall is cooler and darker; it does not declare its texture loudly, and in that restraint the pot’s rounded silhouette grows in authority. Negative space is treated as positive information—an early sign of Matisse’s lifelong sensitivity to the shape of emptiness.

The Rhythm Of Diagonals

Although the still life is compact, it contains movement. The slanted fore-edge of the top book launches a diagonal toward the mug. The mug’s body curves upward and carries the eye to the brighter lid of the pot, whose handle arcs back to the books. This slow circulation keeps us engaged without theatrics; it also gives the cluster a sense of inevitability, as if the things had slid into a natural accord. In later interiors Matisse will choreograph the dance of chairs, tables, and plants with comparable quiet authority. The seeds of that choreography are here.

A Painter’s Signature And Self-Possession

Matisse signs discreetly at the lower right, his name settling into the same tonal key as the tabletop. The signature neither shouts nor hides; it is simply part of the painting’s rhythm. That modesty fits the overall attitude. The work does not push to impress; it offers a calm, disciplined gaze, assured that clarity will persuade more deeply than spectacle. For a painter who would soon astonish Europe with audacious color, such self-possession is striking. He is already listening closely to his subject and allowing it to dictate the manner of its depiction.

From Study To Future Practice

Still lifes would remain a lifelong workshop for Matisse. In the first decade of the twentieth century he would explode color relationships in table settings and vases of flowers; in Nice he would stage interiors whose textiles compete joyfully for attention; in the cut-outs of his last years he would reduce table, plant, and bowl to the dance of shapes alone. What we see in “Still Life with Books” is the bedrock enabling all that: an exact sense of value, a respect for how light reveals matter, an understanding that composition is a structure of relations. The painting teaches that daring color, when it comes, can only be convincing if the underlying tonal scaffold holds.

The Intimacy Of Scale

Part of the picture’s charm lies in its refusal to be monumental. The viewpoint is near, the objects life-size, the table edge close to our hands. That proximity invites empathy; we lean in as one does to an open book. The modest scale also allows Matisse to tune small transitions finely—the shade that creeps along a spine, the flicker of highlight at the mug’s lip, the slightly bluish chill of shadow where the pot lifts off the table. Such nuances can be lost in grand statements; here they are the statement.

Handling Of Time: The Present Held Gently

Still lifes inhabit present tense, yet they often smuggle in time. The worn bindings of the books, the nicks on the pot’s rim, the softening of the mug’s glaze at the handle all record use. A day’s rhythm is implied: reading interrupted, drink finished, work paused. Nothing is dramatic; time is held gently, as if the painter wished to honor the ordinary hours in which knowledge and craft accrue. That temporal humility is central to the painting’s mood. We are not witnessing an event but entering a duration—the kind of duration in which a painter slowly learns his tools.

The Tabletop As Theater

The table is both stage and actor. Its light plane offers contrast to the dark wall, but it also participates in the drama of texture. Matisse roughens its surface with quick, semi-dry strokes, letting warm underlayers peep through. Where the mug’s shadow pours leftward, he cools the tone; where light strikes near the books’ corners, he lifts value just enough to break the plane. The table gathers the objects into a small republic, and its own surface—neither pristine nor ragged—suggests a studio desk that has served faithfully.

The Ethics Of Restraint

For all its painterliness, the work is fundamentally restrained. Matisse resists the temptation to add narrative frills or spectacular lighting. He refuses the shallow trick of describing every detail; instead he offers the viewer tasks—complete the curve here, infer a rim there. This trust in the viewer is part of the painting’s moral stance. It believes that attention is a form of care, that quiet description honors its subject more deeply than flourish. That ethic will underpin Matisse’s later boldness; even his strongest colors are tender because they grow from disciplined looking.

How The Eye Moves

Standing before the picture, the eye usually starts at the bright fore-edge of the front book, slides to the mug’s white rim, circles its blue body, hops to the brass hinge, and then wanders the pot’s warm circumference before returning along the books’ spines. This loop is not accidental; the painter has placed lights as stepping-stones. He has also staged counter-moves: the darker interstices pull us back, asking us to test what we think we saw. The result is a viewing experience that is both restful and active—restful because the arrangement is stable, active because the details keep rewarding second looks.

An Early Manifesto In Disguise

Painted with calm means, “Still Life with Books” quietly declares positions that will guide Matisse for decades. Form is a relation of colored planes, not an outline filled in. Light is a structure, not merely a shine. Meaning arises from the meeting of materials and the care taken in their description. The everyday can carry grace if looked at with patience. These are not slogans but working convictions, and in this painting they are tested against resistant facts: paper, glaze, brass, shadow. The test succeeds; the objects feel at once themselves and more than themselves.

Why The Painting Matters Now

Viewers today often come to Matisse through the spectacular—the Red Studio, the Nice odalisques, the radiant cut-outs. Returning to this early still life enriches those encounters. It shows the beginnings of the craft that makes the later freedoms believable. It invites a slower, more contemplative relation to art and to things. In an age of speed, the painting models attention as a discipline and a pleasure. Books, a mug, a pot: three quiet presences that teach us how to look, and in looking, how to rest.