Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

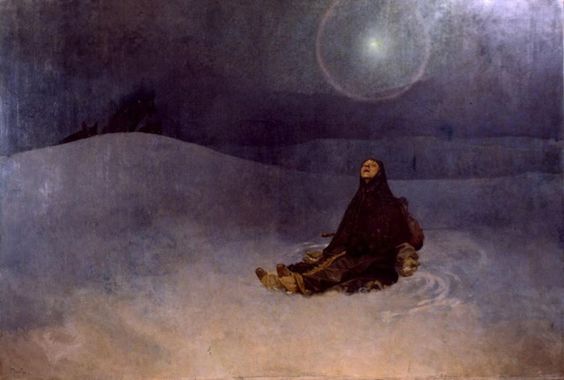

Alphonse Mucha’s “Woman in the Wilderness” (1923) is a late, austere masterpiece that distills a lifetime of visual music into a single, nearly silent note. A lone figure sits on a frozen plain under a deep night sky. Snow dunes curve like sleeping waves. High above, a luminous orb encircled by a pale halo holds the firmament, while the woman, cloaked and motionless, lifts her face toward the light. The surface is restrained, the palette limited, the composition spare. Yet the painting feels inexhaustible because it stages the simplest, oldest drama there is: a human being set against the immensity of the world and answered—if not with speech—then with presence. Where Mucha’s early posters dazzled Paris with ornament, and The Slav Epic unfurled pageants of history, this image speaks in the stripped vocabulary of solitude, winter, and sky.

Historical Moment and the Pivot to Interior Scale

By 1923 Mucha had completed the most grueling chapters of The Slav Epic and had lived through the birth of Czechoslovakia, the trauma of world war, and the new nation’s fragile first years. His art had carried both the glamour of fin-de-siècle Paris and the slow gravity of national myth. “Woman in the Wilderness” belongs to the chamber-music strand of his late work, a group of paintings where he exchanged civic spectacle for interior weather. The canvas reads like a meditation after a long day’s labor—an artist who spent years composing murals of crowds now choosing to paint one person listening to the sky. The austerity is not merely stylistic; it is an ethical choice, a vote for attention over display at a time when Europe was trying to relearn the uses of quiet.

Composition and the Architecture of Vastness

Mucha builds the image on a radical distribution of emptiness and weight. The lower band holds the figure, small and slightly off center, seated on a low drift with knees bent and hands turned upward. Behind her, a chain of snow dunes rises and falls in gentle counterpoint, pushing the eye toward the horizon’s soft ridge at left where a dark grove of trees or distant travelers barely interrupts the monotony. The upper two-thirds are given to the sky, which is not a flat field but a layered volume of indigo, iron blue, and veiled light. From the sky’s center a circular halo expands, almost perfectly concentric, like a lens or a nimbus around a star. Because the orb is lifted almost to the top edge, the viewer feels the axis of the world tilt back, the way one must lean in order to look up at winter constellations. The woman is the painting’s anchor; the sky is its engine; the distance between them is the work’s true subject.

The Gesture of Looking and the Ethics of Witness

In Mucha’s posters, women look out at us with invitation or command; in his epics, crowds gaze toward ceremonial action. Here the woman looks upward and away. We see the underside of her chin, the open shape of her mouth, the soft line of the nose thrown into profile by star-glow. The gesture is prayer-adjacent without being pious. It’s a human reflex before wonder—head back, throat open, defenses down. The position of her hands and the relaxed fall of her cloak intensify the sense that we are witnessing not a staged scene but a genuine encounter with cold, light, and the thought that arrives when words fail. Mucha’s refusal to dramatize the body turns the gaze into the only drama that matters.

Color, Light, and the Temperature of Silence

The palette leans to blue-violet, graphite, and chalked white, relieved by the warm brown of the woman’s boots and a faint, rosy undertone at her cheek. Nothing is saturated; everything is a degree of hush. The sky’s halo is rendered not as an illustration of a halo, but as weather—the optical ring one can see around moon or bright star when ice crystals in high clouds refract light. That meteorological specificity grounds the image in the real even as it opens to symbolism. The snow holds light like breath caught in wool; the cloak swallows it; the ring in the sky releases it back. Because the color range is so narrow, tiny variations carry vast weight: a whisper of green at the halo’s rim, a smudge of violet in the shadow thrown by the woman’s knees, the slightly warmer darkness where her cloak laps over her lap. The sum is an emotional temperature that can only be called listening.

Negative Space as Meaning

Most paintings fill; this one clears. The large unpeopled zones are not empty—they are a medium in which the experience happens. The viewer’s eye is asked to travel across unmarked snow, to pause where wind has scribbled an eddy, to drift up a slope of sky toward a star that does not shout. The effect is to slow time. You become aware of breath, of the faint ringing of cold. In The Slav Epic, Mucha used atmosphere to bind crowds; in “Woman in the Wilderness,” he lets atmosphere be the crowd. The negative space is the congregation and the sermon at once.

Symbolism Without Slogans

The title invites allegory. A “woman in the wilderness” echoes biblical and folkloric narratives of flight, exile, vision, or trial. One thinks of the figure in Revelation who flees into the wilderness and is nourished there, of Mary in winter journey images, or of Slavic tales in which the landscape shelters seekers and the lost. Mucha does not paste symbols onto the figure; he lets the conditions themselves—winter, night, star—carry meaning. The woman is neither saint nor victim. She is what the viewer can be: a person who endures the cold long enough for something to show itself. If one wishes to read the painting nationally, the woman becomes a personification of the young republic persevering through lean years, held by a star that is guidance rather than guarantee. The image can also be read personally: the moment when an artist or any seeker sits still enough to recognize that silence contains an answer.

The Halo as Quiet Technology of the Sacred

Mucha has always loved circles: they appear as theatrical medallions in his posters and as floating processions of saints in the epics. Here the circle is stripped down to a physics lesson—the ring of light a winter night sometimes gives to the patient eye—yet it functions as all haloes do. It separates, concentrates, and dignifies. Placed high and small, it avoids the sentimental. The circle’s near-mathematical perfection reads as a law of the world rather than a special effect. It makes the sky look aware. The woman’s uplifted face acknowledges that something aware is looking back.

Line and the Discipline Beneath the Haze

Even in so hushed a painting, Mucha’s draftsmanship is decisive. The lines that matter most are few: the curve of the cloak over the knee; the profile line that gives the head its exact tilt; the hard little crescent of a boot sole catching light; the ripple of wind-carved snow circling the seated body like a faint mandorla. Elsewhere, edges dissolve into gradation so the eye can rest. This calibrated alternation of firm and soft gives the image its legibility from distance and its tenderness up close. The painter who could mesmerize the street with a single contour now uses line to secure a silence that will not collapse.

Surface, Technique, and the Breath of Paint

Mucha’s late technique—thin casein or tempera underlayers with oil glazes—creates a matte luminosity perfect for moonlight. The sky reads as veils laid one over another until a diffused glow arises from within. The snow is not enamel; it is sifted pigment that looks as if it might blow away if you exhale. Earth tones in the figure are built with opaque touches, providing a physicality that anchors the airy field. The result is a surface that seems to have inhaled the cold and is now exhaling it slowly across the viewer’s face.

The Soundtrack of the Picture

Everything heard here is subtle. Snow squeaks under boots; wind skates along the crust and makes small swirls; distant branches give off a dry, silvery chatter; breath lifts and whitens. If you listen longer, the painting persuades you to imagine the faintest hum from the halo, the near-inaudible hiss that the night sometimes makes when the eye dilates. Mucha often painted scenes that carried music—liturgy, preaching, processions; the music here is the kind that trains the ear to hear itself. The effect is not the absence of sound but the presence of attention.

The Woman as Every-Seeker

A remarkable aspect of the painting is the figure’s lack of theatrical identity. Her cloak is plain; her age indeterminate; her posture universal. The artist denies the viewer any easy label—peasant, saint, allegory of a nation—so that the encounter can be specific to whoever looks. The pose is also practical; anyone who has sat on snow recognizes the economy of tucking feet close and keeping the cloak wrapped. This fidelity to lived gesture preserves dignity. The woman is not staged; she is surviving with grace.

Parallels and Conversations Within Mucha’s Oeuvre

“Woman in the Wilderness” converses with earlier and later works like a coda spoken under breath. The star recalls the hovering apparitions and processions in The Slav Epic, now condensed to a single point of guidance. The sweep of snow echoes the nocturne fields of “The Slavs in Their Original Homeland,” yet stripped of horsemen and crisis, turning drama into revelation. The openness of space and the lone seated figure recall the exilic shore in “Jan Amos Komenský,” with the lamp of learning traded for a star that belongs to everyone. If the posters are Mucha’s public voice and the epics his national voice, this painting is the private one.

Time of Day and the Theology of Hour

The star sits in a sky that feels like the hour just before dawn when the cold is sharpest and light begins to loosen the dark. In Christian monastic tradition, that hour belongs to vigils and matins, the prayers for watchers and workers. In folk life it is the hour of bakers and travelers who need the frost to bear their weight. Mucha’s choice of this hour aligns the painting with labor and with readiness. Vision here is not trance; it is the steadiness found by those who have remained awake.

The Viewer’s Role

Mucha composes the scene so that you cannot remain an indifferent spectator. The empty snowfield between you and the figure is also the path you imagine yourself crossing. The cold you feel is the cold the woman feels. The ring of light is not a distant special effect; it is a shape your own eyes know. The painting thus becomes collaborative: it needs your breath, your memory of winter, your willingness to sit. That partnership is what keeps the image from becoming a romantic cliché. It is a proposition to practice attention.

Modernity and the Refusal of Ornament

Despite Mucha’s reputation as an apostle of Art Nouveau, “Woman in the Wilderness” is strikingly modern. The nearly monochrome field, the vast negative space, the single focal figure, and the anti-decorative restraint would not be out of place among Symbolists or early twentieth-century minimalists of feeling. Yet the painting retains the warmth of hand and the clarity of drawing that make it unmistakably his. It shows how a master of flourish can choose austerity without losing identity.

Why the Painting Endures

The painting endures because it provides a usable image of hope that does not cheapen suffering. The woman is cold; the land is empty; the night is long. And still there is a light, small and sufficient, and a circle around it like a promise made by physics itself. The picture does not offer answers; it offers a practice: sit, look, breathe, and allow the world to be large without letting yourself be lost. In an age of noise, such an ethic is radical.

Conclusion

“Woman in the Wilderness” is a hymn written in one note. With snow, sky, a person, and a star, Alphonse Mucha composes a scene that outlives its hour. The line that once shouted from Parisian kiosks now whispers across a winter field; the color that once celebrated pageantry now keeps vigil; the circles that once framed actresses and saints now ring a point of light any wanderer can claim. This is how great artists age: they learn to say more with less, to trade ornament for presence, to trust that a single figure looking up is big enough to carry a world. Mucha’s woman does not conquer the wilderness. She honors it, and in honoring it, finds herself held.