Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

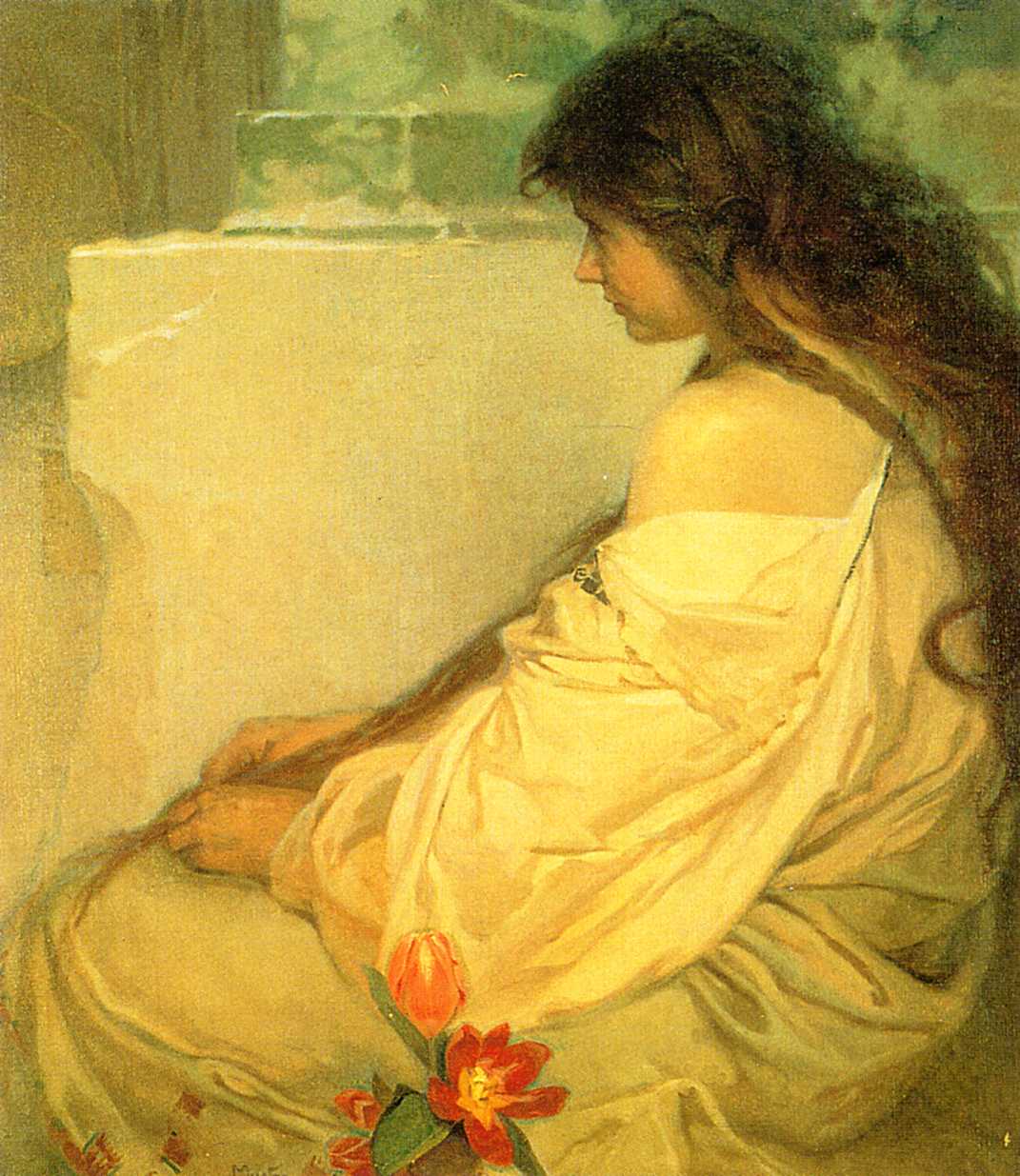

Alphonse Mucha’s “Girl with Loose Hair and Tulips” (1920) is a quiet revelation from an artist best known for dazzling posters and panoramic history. Instead of theatrical arabesques and haloed allegories, he offers a single figure in profile, folded into herself on a low seat, her hair unbound and pooling like evening light across her shoulder. At the painting’s edge, a stem of tulips erupts in warm red and orange, a small flare against a harmony of creams and pale greens. The image is intimate without sentimentality, decorative without display. It reads like a pause—one of those unguarded intervals when the world recedes and thought gathers. Mucha, who had recently completed many of the grand canvases of The Slav Epic, turns here toward the interior, demonstrating that the same disciplined eye that could orchestrate armies and saints could also spend its patience on a quiet girl and the breath of a flower.

Historical Context and a Shift in Scale

The date matters. In 1920 Czechoslovakia was scarcely two years old; Europe was still counting losses after the First World War; and Mucha, long celebrated for his Parisian Art Nouveau, had returned to his homeland to labor on a national cycle. “Girl with Loose Hair and Tulips” belongs to this later period when his palette softened and his attention became more introspective. The canvas can be read as a private counterweight to public ambition, a room-sized answer to the mural-scale epics. Where the epic declared a people’s endurance, this picture suggests how that endurance is felt—in a body at rest, in a sleeve eased off the shoulder, in hair released from propriety. The painting is not programmatic. It is personal, and its intimacy is precisely what makes it feel modern after a decade of theater and politics.

Composition as a Chamber of Quiet

The composition is composed like a chamber piece. The girl sits in strict profile, occupying the right two-thirds of the canvas. Her body forms a gently sloping triangle from head to gathered hands, and the shawl or dress she wears falls in generous folds that round the form without angularity. Behind her, a pale wall absorbs light; above it a cool strip suggests a ledge or window whose color drifts toward green, hinting at an exterior the figure ignores. The tulips, painted near the lower left edge, counterbalance the mass of the figure and keep the canvas from tipping into monotone. Nothing unnecessary intrudes. Mucha reduces the stage to three actors—figure, ground, and flower—and then conducts them with the restraint of a master who trusts small moves.

Pose, Psychology, and the Ethics of Attention

The girl’s pose is a study in inwardness. Her head inclines slightly; her eyes look down; her hands, barely visible, gather the loose weight of her hair or knit fingers in thought. Shoulders soften under the light fabric, and the neckline slips just enough to reveal the roundness of skin without performance. It is a contemplative posture, not a coy one. Mucha declines the direct gaze that animates his poster beauties; he gives us a person absorbed, allowing the viewer to practice the same. This ethical posture—of attention without intrusion—governs the mood of the picture. We are not voyeurs, and she is not exhibition. We are sharers of a pause.

Hair Unbound and the Language of Freedom

Mucha has always been a poet of hair, transforming it in his commercial work into ribbons of ornament that swirl like smoke around actresses and allegories. In this painting the hair is uncoiled and heavy, a river rather than a scroll. Its loose fall carries cultural and psychological connotations: privacy, release from social ritual, the moment after work when pins are removed and the body remembers itself. The hair is not glossy or idealized; it keeps the color of the room’s air and the warmth of the neck where it rests. Its long diagonal unites head and hands, closing the form into a self-sufficient loop that reads as calm rather than enclosure. Hair becomes the line by which the body listens to itself.

Tulips as Counterpoint and Symbol

At the lower edge, tulips blaze. Their red and orange arrive after a long passage of creams and pale greens, like a brief chord in a minor key that brightens the ear without turning the piece cheerful. Tulips—spring flowers that close and open with temperature and light—mirror the girl’s poise between privacy and disclosure. Their bulbs suggest storage and survival; their sudden flare suggests readiness to bloom when the weather allows. Mucha does not overpaint them; he keeps their petals simple and shaped by light, letting their color rather than detail provide emphasis. They are both counterweight and companion, a natural emblem of youth kept at the painting’s edge where it neither intrudes nor vanishes.

Color, Light, and the Atmosphere of After-Glow

The painting’s color is built from the grammar of warmth and hush. Pale ochers and ivory define the garment and wall; the background leans to cool, breathable green, like shade seen from indoors; flesh tones gather honey from the surrounding creams. Light seems to arrive from high left, sliding across the shoulder and descending the folds into a pool at the lap. There is no hard edge to the illumination. It functions as after-glow, the light of a late afternoon whose source is less visible than its effect on cloth and skin. The color harmony produces a feeling of mild air and settled temperature, as though a door has just been closed and the room has reclaimed its climate.

Fabric and the Pleasure of Tactility

One of the painting’s chief pleasures is the fabric itself. Mucha paints the garment with a combination of long, fluent strokes and small inflections at creases and seams. The cloth looks substantial rather than airy; it gathers into weighty folds that register gravity. The shoulder seam, the fall of a cuff, and the stretch across the lap are described with enough certainty to make the viewer feel the garment’s heft. This tactility is important because it grounds the figure’s inwardness in body rather than dream. The picture is neither symbolic nor anecdotal; it is a record of substance—cotton or linen taking the shape of a resting torso, light pulling color up from woven fibers.

Draftsmanship Beneath the Haze

Though the surface glows with softness, Mucha’s disciplined drawing holds it together. Small, decisive edges anchor the profile, knuckles, and hems; the far shoulder is allowed to melt into light, but the nose and lips remain firm. The tulips are built from a few accurate turns; the background blocks, perhaps a window or niche, maintain their geometry through quiet tonal shifts. This is a painter who knows exactly where to let air enter the form and where to keep the skeleton visible. Such control allows the mood to expand without the structure collapsing—a hallmark of his mature technique after decades of balancing design and observation.

Space and the Threshold Between Interior and Exterior

The setting hints at an architectural threshold. That cool, greenish band above the wall reads as a ledge with stone beyond it—perhaps a studio window, perhaps a courtyard. The figure sits inside that threshold, turned away from whatever the exterior offers. The resulting space feels like a room that protects rather than isolates. The world is present enough to tint the color, but not so emphatic that it demands attention. Viewers who know Mucha’s larger themes will sense the metaphor: after the public labors of nation and history, interiority becomes the necessary room where future work is prepared.

Continuity with and Departure from Art Nouveau

“Girl with Loose Hair and Tulips” converses with Mucha’s famous Art Nouveau vocabulary while also leaving it behind. The profile silhouette, sinuous limits, and ornamental accents recall posters of actresses and allegories; the tulips echo the organic motifs he loved to repeat in borders and medallions. Yet the painting eschews overt patterning, typography, and haloed frames. It keeps its distance from stylization, choosing instead the stubborn particularity of a single head of hair and a single drop of fabric at the shoulder. The departure is not rejection; it is evolution. The designer’s eye remains, now serving observation rather than commerce.

Gendered Presence and the Non-Theatrical Female

Mucha’s women often personify abstract ideas—seasons, stars, virtues. This girl is not an allegory. She is unobserved except by the painter and the viewer, unadorned except by her own hair and garment, unassigned to the duties of muse. The pose conveys independence without rhetoric. In an era that frequently staged women as instruments of style, this picture respects a non-theatrical female presence: thinking, resting, not-yet-performing. The tulips—traditionally freighted with courtship and gardens—do not reduce her to an object of desire; they echo her self-possession, blooming near but not upon her.

Time, Memory, and the Mood of Afterthought

What sets the painting apart is its temporal mood. It feels like afterthought: the moment after a conversation has finished, after a day’s work has ended, after hairpins have been set aside. This “after” is not melancholy; it is preparatory. The figure’s inwardness reads as sorting, remembering, letting meaning settle. Mucha, who had spent years organizing historical memory on the grand scale, here paints memory at the scale of a single body. The picture suggests that cultural endurance is made of thousands of such quiet afterthoughts in which meaning consolidates.

Technique, Surface, and the Breath of Paint

The surface is matte, built from thin veils that allow earlier tones to breathe and thicker strokes that catch light at key edges. The wall’s paleness includes greens and pinks that keep it from chalk; the garment’s highlights are creamy rather than white. The tulips receive more saturated pigment but remain integrated into the same breathy atmosphere. The handling is frescolike without chalkiness, a technique Mucha used throughout The Slav Epic and adapted here for intimacy. The paint itself seems to keep the air—less a glaze than a memory of the brush passing and leaving behind warmth.

The Flower-and-Figure Dialogue

The most subtle achievement of the painting may be the dialogue between flower and figure. The tulips appear as if they have just been placed or have drifted into the frame on a cloth; their stems angle upward toward the girl, and her profile returns the gesture with a soft diagonal of attention. No literal line connects them, yet the eye moves easily from petal to cheek, from stem to forearm. The flowers’ saturated red dampens into the garment’s ocher, while the garment’s warmth echoes faintly back into the petals. This exchange creates a visual and emotional ecology: youth converses with bloom, privacy with display, endurance with flare.

Reading the Painting as a Domestic Icon

Within Mucha’s oeuvre, the picture functions as a domestic icon. Instead of saints or martyrs, it venerates rest. Instead of grand narratives, it sanctifies a seam and a fold. It invites viewers to set it in their own interior rooms as a reminder that attention can be practiced in ordinary light. The lack of overt symbolism makes it hospitable across contexts; it can belong to households that prize art, to studios that prize craft, and to readers who find in a profile the encouragement to think.

Influence, Legacy, and the Late Mucha

Paintings like this one have often been overshadowed by Mucha’s posters and by The Slav Epic, yet they explain how his signature line and color achieved their humane authority. When designers and painters after him sought to combine decorative clarity with psychological nuance, they found models in these late portraits and studies. The painting also foreshadows the quieter currents of twentieth-century art that valued private states over public drama. In a world that would soon be tested again by political storms, “Girl with Loose Hair and Tulips” insists on the dignity and cultural necessity of a single unguarded hour.

Conclusion

“Girl with Loose Hair and Tulips” is a small masterclass in restraint. A profile in cream, a whisper of green, a flame of red: from these simple means Mucha composes a lasting mood. The picture holds its ground quietly, teaching the viewer to meet it on its terms—slowly, attentively, without the expectation of spectacle. It reminds us that the same hands that drew glamorous posters and national epics were also capable of honoring a shoulder’s curve and the bloom of a tulip. In doing so the painting becomes a promise: that culture survives not only in monuments and public squares, but in rooms where someone sits alone with unbound hair, thinking in the company of flowers.