Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

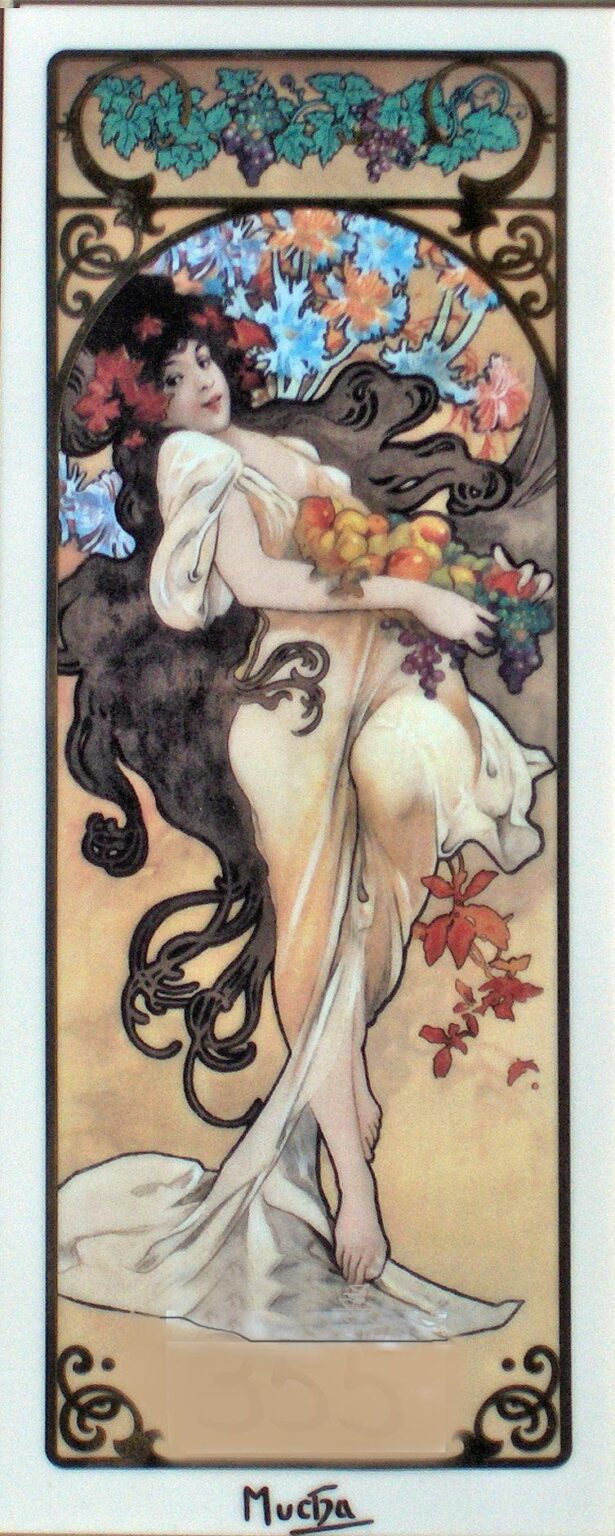

Alphonse Mucha’s “Amethyst” (1897) stages abundance with the poise of a cameo. In a tall, narrow panel a young woman steps forward from a flowering alcove, her body wrapped in pale, liquid drapery that slips across the surface like silk. She carries grapes and orchard fruit against her breast while her dark hair unspools in whiplash curves that braid the picture together. Above her, a frieze of grape leaves and clustered amethyst-purple fruit crowns the design; around her, a sinuous border cinches the scene like a piece of jewelry. It is a portrait of a gemstone by way of nature: purple suggested not only by pigment but by the idea of the vine, the perfume of harvest, and the mythic history of wine.

A Gemstone Imagined as a Woman

Mucha’s decorative panels often personify abstractions—seasons, flowers, arts, even hours of the day—by turning them into women whose demeanor carries the theme. “Amethyst” belongs to this tradition. Rather than display a cut stone, he distills the gem’s associations into a figure: the crown of grape leaves, the armful of fruit, the mauve and violet accents, and the dusky fall of hair that reads as a shadowy echo of purple. In classical lore amethyst was the antidote to intoxication; the stone was believed to keep the mind clear even in the presence of wine. Mucha plays with that paradox. The panel is lush with Bacchic imagery—vines, grapes, sensual drapery—yet the woman’s gaze is lucid, amused, and in control. She embodies delight without surrender, a visual metaphor for the gem’s reputed clarity.

Composition and the Architecture of the Panel

The sheet is organized like a small altar. A rectangular frame encloses a secondary arch that shelters the figure, while ornamental spandrels knit the geometries with tendrils and scrolls. The top register hosts the vine frieze; its horizontal band balances the sweeping vertical of the woman’s stance. Within the arch, a tapestry of chrysanthemum-like blossoms fills the field, their petaled bursts alternating warm oranges with cool, milky blues. Mucha places the figure just off center and tilts her torso in a rhythmic S-curve, so that leg, hips, waist, shoulder, and head create a single elastic line. The dark hair expands behind her in looping arabesques, acting as a compositional counterweight to the pale dress and as a visual bridge between the warm ground and the cool top band.

The Sinuous Line and the Pleasure of Contour

Mucha’s mastery of contour—the long, unbroken line that defines form as decisively as metal outlines enamel—carries the image. The back curve of the figure, the soft swell of shoulder and forearm, the coils of hair that taper to thin filaments, and the scrolls of the corner border all sing in the same key. These lines are not merely descriptive; they pace the viewer’s attention, slowing it at gentle turns, quickening it along tight loops. The continuous edge around the figure gives her the solidity of a carved relief while the interior modeling remains delicate and planar, a signature balance in Mucha’s work between drawing and color field.

Drapery as Movement and Modesty

The dress clings then releases, mapping the body without exposing it. Mucha paints the fabric with minimal modeling—creamy highlights edged by the black keyline—so that the cloth reads as both real and ideal. Where it falls to the ground, the hem spreads like a pale pond, anchoring the figure; where it gathers at the waist, the folds become musical bar lines that measure the rhythm of the pose. The slight twist of the knee and the lifted heel suggest a step, and the drapery responds, opening the figure to the space. It is a composed sensuality, not a tease: movement turned into ornament.

Hair as Binding Agent

The flowing hair is a design engine. It streams behind the figure, loops around the left margin, and curls back toward the gathered fruits, physically tying the panel’s zones together. Never uniformly black, it warms with brown and plum tones that echo the grapes and foreshadow the stone’s purple. Mucha often lets hair perform the work of landscape; here it does more, acting as a dynamic foil for the pale dress and as a series of arabesques that keep the eye traveling. The contrast between the free hair and the controlled border is key: organic energy held within crafted limits, a visual analogue of a gemstone mounted in a setting.

Harvest Iconography and the Myth of Amethyst

The top grape frieze, the clusters in the figure’s arms, and the small cascade of red leaves orbit a theme that ranges from vineyard to myth. The name “amethyst” comes from the ancient Greek for “not drunken,” and the stone’s purple has been linked to wine since antiquity. Mucha plays the symbol both ways. On one hand, the panel revels in the sensual abundance of harvest: fruit spilling forward, hair ripe as a cluster, a body poised like a vine in breeze. On the other, the heroine remains composed, her expression poised, her step measured. She is Bacchic and sober at once, a reconciliation that suggests the refined pleasure of taste rather than excess—the perfect alignment with the gemstone’s lore.

Color, Temperature, and a Gem Without Glitter

Purple need not shout to be present. Mucha builds amethyst through association and harmony rather than literal saturation. He sets the warm parchment ground against blue-lavender blossoms and cool green vine leaves; he tucks violet grapes beside apricot and lemon fruit so that their hue deepens by contrast; he lets the hair’s dusky gloss hint at plum. The face is a clear peach, lips and cheeks touched by rose, skin modeled with the faintest shadows. The total effect is a chromatic perfume: one senses purple filling the air, even where it appears only in accents. The color strategy suits lithography, which excels at flat fields and gentle transitions—it makes the panel read beautifully at distance and feel rich up close.

The Floral Canopy and Seasonal Time

Behind the figure, chrysanthemums—or flowers very much like them—burst in alternating orange and pale blue. They are autumnal by association and graphic by design, radiating stiff petals that play against the soft curves of body and hair. Above them, the grape frieze extends the season upward. This layered botany folds time into the panel: ripeness of early fall at the top, matured abundance at the middle, and the first drift of red leaves near the hem. Without any emblematic captions, Mucha turns “Amethyst” into a calendar of sensuous time, the moment when vineyards look jeweled and the air begins to cool.

The Border as Jewel Mount

The surrounding frame is not merely a boundary; it is the jewel’s setting. Corner volutes twist like chased metalwork; the arch springs from filigree; small roundels punctuate the lower corners like studs. The black keyline that outlines these motifs also outlines the figure, so the body belongs to the same ornamental order as its frame. That harmony makes the panel feel finished, like an object rather than a picture. It also allowed printers to produce variations—sometimes with calendar blocks, sometimes with product text—while preserving the essential design.

Lithography and the Craft of Surface

Printed by a premier Paris workshop, the panel relies on layered color stones and a crisp black keyline. Mucha designs for the process with an engineer’s sense of tolerance. Large flats—skin, dress, ground—are left smooth so minor misregistrations are forgiving; complex textures—hair, leaves, blossoms—are built from the keyline first and then filled with transparent inks that can float inside the lines without demanding perfect edges. Highlights are often reserves of the paper’s own white, especially along the dress and fruit. The result is luminous and clean, a sheet that glows rather than glistens.

Face, Gesture, and the Manner of Address

Mucha’s women rarely confront aggressively; they invite by temperament. The heroine of “Amethyst” turns her head toward the viewer with a conspiratorial half smile, neither coy nor indifferent. One hand steadies the cornucopia of fruit; the other gathers grapes, poised to offer or to keep. The gesture is ambiguous in the best way; it suggests generosity without organizing a narrative. She is an emblem of a state of mind—pleasure, sufficiency, lucidity—not a character in a story. That economy is central to Mucha’s decorative language, which strives to maintain mood while minimizing event.

Between Poster and Panel

Many of Mucha’s images began life as commercial posters and were republished as decorative panels; others were conceived from the start as pure decoration. “Amethyst” sits comfortably in either realm. Nothing in the design prevents a headline from occupying the blank lower cartouche, and yet the image needs no words to function. This pliability was part of Mucha’s appeal to publishers and the public alike: his art could dignify advertising and still feel at home on a living room wall. The panel renders value by offering refinement that never feels borrowed from a different context.

Cultural Context and the Femme-Idole

Fin-de-siècle Paris adored the fusion of ideal woman and ideal object. Mucha’s figures are sometimes called “femmes-idoles,” not because they are passive idols, but because they stand in for intangible ideals. “Amethyst” extends that idea to the domain of mineral and myth. The woman is the stone; the stone is an attitude; the attitude is the life of an era discovering luxury as a form of inward pleasure. Unlike harsher contemporaneous images that objectify or caricature, Mucha’s emblem is gently autonomous. Her body is stylized, but her face remains individual, tender, and alert. The balance gives the image a longevity beyond fashion.

The Viewer’s Path Through the Image

The eye begins at the vine frieze, descends the curve of the arch, lands on the face, and then follows the dark hair as it loops down the left side toward the pooling hem. The fruit interrupts with color and weight, inviting a second circuit across the arms and back up to the blossoms. This circular tour is important: it keeps attention within the panel while allowing quick comprehension from afar. Even a passerby glancing for a second will catch the essentials—woman, grapes, hair, arch—and read the mood correctly. Those who linger will find the smaller pleasures: the crisp cut of a petal; the way the hair’s line reappears in the lower corner scroll; the faint violet that threads the grape clusters together.

Why “Amethyst” Endures

The panel’s survival in reproductions, tiles, and household objects for more than a century is not accident. It delivers a sophisticated idea with ease: that sensuality can be lucid, that luxury can be restful, that ornament can clarify rather than clutter. It asks little of a room and gives a lot in return—a mellow light, a sense of ritual harvest, a graceful figure whose presence is companionable. The gem itself becomes a way to think about living: polished, calm, and alert to delight.

Conclusion

“Amethyst” reveals Mucha at the height of his decorative intelligence. A woman personifies a stone, and a stone becomes a season; hair becomes architecture, and a border becomes a jewel mount. Grapes, blossoms, and ribbons of line weave the panel into a single fabric that reads instantly and rewards sustained looking. The mood is ripe but clear-headed, exactly what the gem’s myth promises. In an age learning to make beauty part of everyday life, this sheet offered a model of how to do so gracefully: with balance, with craft, and with a generosity that still feels fresh.