Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

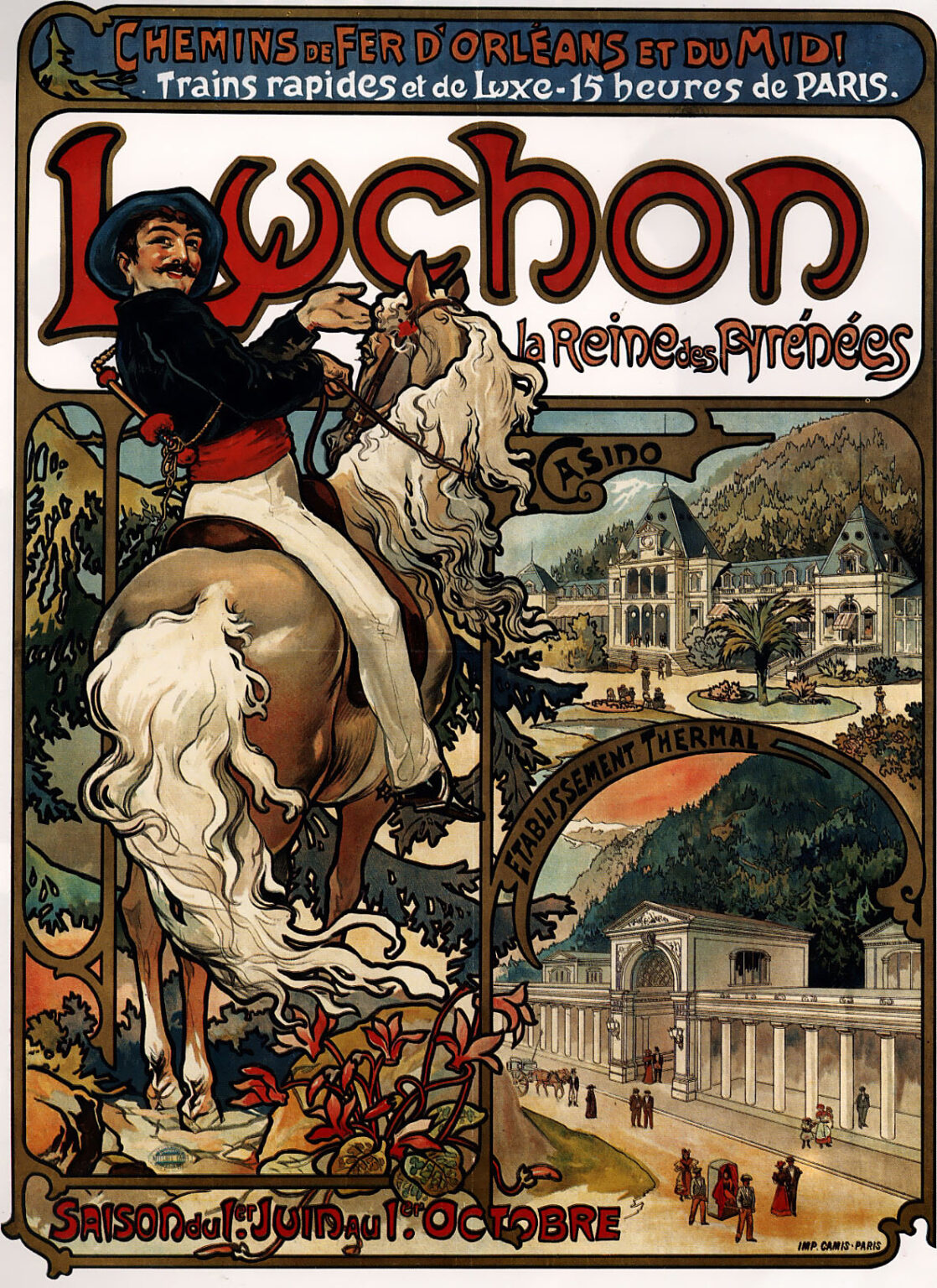

Alphonse Mucha’s “Luchon” (1895) is a model of the Belle Époque travel poster: persuasive, glamorous, and exquisitely crafted. Commissioned to promote the spa town of Bagnères-de-Luchon in the French Pyrenees for the Chemins de fer d’Orléans et du Midi, the lithograph sells more than a destination; it choreographs a whole experience—swift rail connections, fresh mountain air, glittering casinos, and curative thermal baths—within a single, carefully orchestrated page. A rearing white horse carries a proud local rider in the foreground, while nested vistas open onto manicured gardens and grand architecture. Around and through the picture runs Mucha’s unmistakable Art Nouveau vocabulary: supple arabesques, ornamental type, and a decorative border that binds text, figures, and landscape into one flowing harmony.

The Belle Époque Poster as Total Design

By the mid-1890s, color lithography had transformed the streets of Paris into outdoor galleries. Mucha was among the first to understand the poster as a total design—image, lettering, and ornament planned together. “Luchon” reads at a glance from across the boulevard: the town’s name appears in a large, rounded script banded with shadow; above, the railway headline promises “trains rapides et de luxe,” and below, a seasonal banner (“Saison du 1er juin au 1er octobre”) closes the frame. The typography is not pasted onto a picture; its curves rhyme with the horse’s tail, the mountain outlines, and the botanical scrolls, so the advertisement behaves like a single musical phrase. Mucha’s integration of copy and image was revolutionary for travel publicity and remains a benchmark in graphic design education.

Composition and the Theatrical Foreground

Mucha anchors the sheet with a diagonal thrust: a horseman in local dress turns his mount to face the viewer, the animal’s mane and tail tumbling in wavelike strands. The rider’s red sash and cocked hat announce regional character; he is both a guide and a mascot for Luchon’s identity. The pose is deliberately theatrical. The horse rears at the picture’s edge, creating a curtain-like foreground that parts to reveal the spa town beyond. This is a classic advertising tactic—stage the encounter with a charismatic figure, then reveal the product’s world behind him. In “Luchon” the tactic is sublimely Art Nouveau: the foreground’s sinuous contours lead the eye in long, unbroken arcs from hoof to tail to reins to lettering.

Nested Vignettes: Casino and Thermal Establishment

Behind the figure, Mucha organizes information through vignetted windows labeled “Casino” and “Établissement Thermal.” Each frame presents a carefully selected amenity: landscaped promenades, grand façades, and strolling visitors. The vignettes function like chapters in a travel brochure, but they also help the viewer move through space. From the alive, tactile horse in the foreground, the eye travels to the middle distance of gardens and finally to the crisp geometry of colonnades and arches. The structural clarity—ovals and scrolls that contain scenes—keeps the sheet readable despite the abundance of detail. It is also practical: printers could emphasize a town’s signature architecture, leaving no doubt about the destination’s prestige.

The Railway Message and Modern Mobility

At the top margin, a broad blue cartouche declares the sponsoring rail lines and the journey time (“15 heures de Paris”). This is the poster’s promise of modernity. Below, Mucha offers antiquity’s gifts—mountains, springs, and healing waters—but he frames them within the miracle of contemporary speed. The pairing is potent: the viewer is invited to move effortlessly from urban life to pristine nature, from the bustle of Paris to the restful Pyrenees, without sacrificing luxury. In the Belle Époque imagination, the railway was not merely transport; it was a conduit to health, leisure, and status. “Luchon” communicates that dream with poise.

Color Strategy: Earth, Sky, and Accents

Mucha builds the palette on tempered earth tones—olive greens, ochres, and warm stone—cooled by sky blues and animated by select accents of vermilion and creamy white. The white of the horse’s mane whips across the lower left like a band of light, echoed by the white columns of the thermal building. These highlights serve both aesthetic and informational roles: they catch the eye and they guide it to the town’s most prestigious features. The reds, reserved for the rider’s sash and the town name, bind human identity and brand identity together. Mucha’s use of color is never merely decorative; it is hierarchical, giving the viewer a ladder of attention: name, hero figure, amenities, schedule.

Line and the Art Nouveau Arabesque

Poster reproduction in the 1890s favored flat areas of color bounded by decisive contour. Mucha turned that technical constraint into a style. In “Luchon,” the arabesque line defines everything from the horse’s muscles to the foliage that curls around the frame. These lines are neither purely naturalistic nor purely abstract; they are stylized enough to flow as pattern and descriptive enough to model form. This duality—pattern that is also picture—embodies Art Nouveau’s ambition to dissolve the boundary between fine art and applied art. The result is an image that communicates information and offers the viewer a sensual rhythm of curves and counter-curves.

Ornament as Information Architecture

The poster’s border is not a frame tacked on after the fact; it behaves like a navigation system. Scrolls point to labeled vignettes; plant forms at the bottom echo the climatic appeal of the Pyrenees; bracketed corners stabilize the layout. Even the little flourishes around the season dates are tailored to the overall curve language. Mucha’s triumph is to make ornament practical. In a street filled with competing posters, ornament that also organizes content helps a passerby understand the message within seconds. This is why his advertising remains legible even at a distance or from a moving carriage.

The Hero as Emblem of Place

The rider’s costume—broad hat, dark jacket, bright sash—distills regional folklore into a welcoming emblem. He is modern (he peers back with a knowing smile) and rustic (he rides among pines and rocks). The figure invites the viewer not just to a destination but to an identity: Luchon as “la reine des Pyrénées,” proud and hospitable. This balancing act matters. Spa towns depended on both international travelers and local pride. Mucha stages their reconciliation: the railway brings you swiftly; the mountains receive you warmly; and local culture serves as authentic host.

Architecture and the Spa Ideal

In both vignettes, architecture is character. The casino’s turreted roof and the thermal building’s vast portico broadcast refinement and scale. People are small—tiny walkers and carriages—so the buildings become the social stage on which health and pleasure occur. Mucha understood the typology of spa architecture: porticoes for shade, promenades for gentle exercise, and pavilions for music, gaming, and conversation. In “Luchon,” architecture crowns the landscape rather than dominates it; mountains and trees remain present, ensuring that the promise of cures rests on nature’s authority.

Lithographic Craft and the Printer’s Role

The imprint in the lower right credits Imp. Camis, Paris, one of the accomplished lithographic houses of the period. Mucha typically prepared a detailed design which the printer then separated into multiple stones—one for each color. The crispness of the blacks, the evenness of the blues, and the subtle osmosis between greens and browns all testify to expert stone handling. The poster’s legibility across tones—brights, mid-values, and shadows—relies on this craft. It also explains why original impressions retain such appeal: the matte inks and paper absorb light in a way digital reproductions struggle to mimic.

Narrative of Leisure: A Day in Luchon

“What will I do there?” The poster answers with a miniature itinerary. In the lower vignette, visitors arrive in carriages, walk beneath arcades, and enter the baths; in the upper scene they stroll through gardens toward the casino and social life. Nature, health, society—three pillars of the spa experience—are all present. The foreground flora (lilies and curling leaves) act like a prologue, reminding the viewer that even luxury rests on the soil. The horseman, meanwhile, frames the experience with movement: he brings you to the threshold, then turns back as if to say, “Your turn.”

Typographic Character and Brand Voice

“Luchon” appears in a rounded, shaded script that is unmistakably Mucha: soft terminals, generous counters, and a subtle internal line that gives the word the three-dimensional buoyancy of signwriting. The railway headline is set in capitals with interpuncts and outline shading, dignified yet friendly. Throughout, the letterforms echo the poster’s curves; nothing feels pasted on. Mucha understood that the name itself is the product. When spoken aloud, “Lu-chon” has a pleasant lilt; when seen in his lettering, it gains a tactile warmth that suggests both approachability and prestige.

Local Nature, National Network

A profitable travel poster must sell both specificity and accessibility. Mucha marries them by placing Luchon’s highly local flora, costume, and mountains against the national reach of the railways. The top banner becomes a civic guarantee: this alluring scene is not remote fantasy; it is precisely 15 hours from Paris by fast, luxury trains. By including exact logistics, Mucha speaks both to imagination and to planning instinct. The viewer exits not only charmed but informed.

Motion, Time, and the Viewer’s Path

The poster is engineered to be read in three beats. First, the town name and the horseman capture attention; second, the eye drops to the season dates and the path curling toward the thermal establishment; third, the gaze returns to the casino vignette and out through the mountains. This clockwise circuit uses diagonal thrusts and curved borders to keep the eye looping. Motion implies time; time implies journey; and journey is the product the railways sell. Mucha thus builds time consciousness into the very act of looking.

Art Nouveau Ideals Embodied

“Luchon” exemplifies Art Nouveau’s core ideals: unity of the arts, reverence for organic line, and an ethical belief that everyday objects—posters, menus, labels—should be designed with the same care as “high art.” The arabesque connects typography to tail hair; the border morphs into landscape; utilitarian text becomes ornament. Even the notion of cure at the spa dovetails with the movement’s optimism: design can improve life, making travel smoother, leisure more cultured, and the city more beautiful.

Comparing “Luchon” with Mucha’s Theatrical Posters

Only months earlier Mucha had stunned Paris with his poster for Sarah Bernhardt. In those theatre works, he often presented a single iconic figure haloed by ornamental panels. “Luchon” adapts that approach to the demands of tourism. The iconic figure remains—the horseman—but the halo becomes narrative vignettes where amenities must be legible. The color key is slightly earthier, appropriate to a mountain resort rather than a mythic stage role. What doesn’t change is Mucha’s commitment to legibility through ornament: whether selling a play or a place, he makes beauty do the work of explanation.

Cultural and Economic Subtext

Travel posters of the 1890s participated in a broader democratization of leisure. While the casino and thermal complex imply privilege, the railway message signals accessibility. Mucha’s crowd scenes include not just grand gowns but ordinary walkers. Luchon is cast as a microcosm of Belle Époque society: a place where classes mix under the banner of health, where modern technology delivers ancient benefits, and where the nation’s infrastructure meets the region’s charm.

Why “Luchon” Still Works

More than a century later, the poster remains compelling because it understands human attention. It offers a clear hero, a name that is fun to say and satisfying to see, a set of promises organized by frames, and a path the eye can follow without effort. Its spare palette reads at a glance, yet the details reward a longer look. Most of all, it never treats utility and beauty as opposites. The practical facts—dates, routes, facilities—are delivered through forms that please the senses. That fusion is why Mucha’s travel designs continue to inspire contemporary branding and wayfinding.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Luchon” condenses the promise of a Pyrenean resort into a single, persuasive chorus of image, ornament, and text. A gallant rider ushers us from mountain edge into cultivated leisure; vignettes of casino and baths narrate the day; typography sings the town’s name while the railway banner certifies speed and comfort. Every curve counts, every color serves hierarchy, and every decorative flourish doubles as information architecture. As an artifact of Art Nouveau and a masterclass in graphic communication, “Luchon” remains one of the era’s most effective invitations to travel—proof that a poster can be both a work of art and a machine for desire.