Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

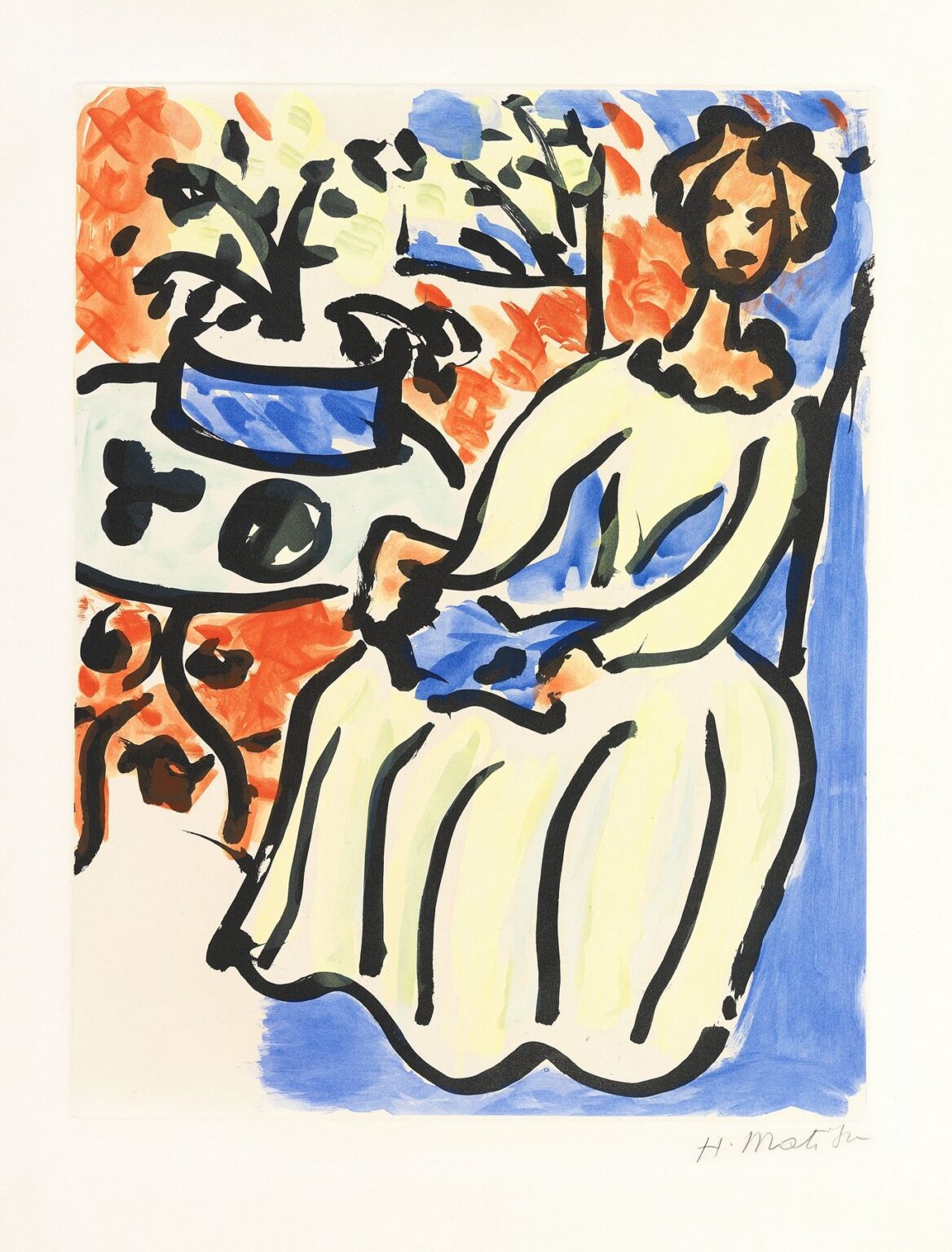

“Marie-José in a Yellow Dress” shows Henri Matisse in late bloom, painting the figure with a shorthand of confident black contours and quick washes of color. A young woman sits turned slightly toward us, her skirt fanning like a bell across a patch of blue floor. The dress is lemon-pale, the shadows painted in strokes of cool gray and sky blue. Behind her, a patterned wall flares in orange and vermilion, while to the left a little round table supports a chunky pot brimming with foliage. Nothing is modeled in the academic sense; everything is declared by the swing and pressure of the brush. The picture reads immediately from across a room, yet its apparent simplicity hides a network of decisions about rhythm, interval, and color balance that Matisse had refined over five decades.

The Late Matisse Hand

By 1950 Matisse’s line behaves like calligraphy. The contour around the sitter’s face, neckline, sleeves, and skirt is a single dark melody that thickens and thins as it turns. This line performs three jobs at once. It draws the figure with economy, it separates warm from cool fields so color can stay clean, and it creates a decorative rhythm that links foreground and background. Matisse often said he wanted a drawing to be “direct,” as if the hand had traveled the shortest path between eye and perception. That ethic governs this portrait. The drawing does not analyze forms piece by piece; it states them, letting the brush’s tempo carry conviction.

Color as Architecture

The palette is a triad—yellow, blue, and red—tempered by the black of the line. Blue anchors the composition and quietly structures space. It pools under the sitter, rises behind her on the wall, and fills the pot and a few leaves, functioning as shadow without behaving like literal shade. The yellow dress, lightly inflected with gray and blue, becomes the source of light itself. Red and orange, pushed to the background, create a warm halo that animates the cool figure without swallowing her. Because these colors sit in distinct, flat fields, they operate like panes of stained glass: it is their adjacency, not a gummy mix, that makes them glow.

A Portrait Built from Big Shapes

Matisse reduces the room to a few readable blocks—a blue patch that reads as floor, an orange-red patch for the floral wall, a turquoise slab for the tabletop. The sitter’s body is also simplified into big, legible shapes: oval head, narrow torso, triangular bodice, and a wide bell of skirt cut by a few vertical seams. The hands are abbreviated—one holding a small blue object, the other resting—but the gesture is eloquent, halfway between posed and relaxed. Because the big shapes are so clear, the eye accepts the scene instantly, and small asymmetries (a shoulder higher than the other, the slight twist of the waist) read as life rather than error.

The Table and Plant as Counter-Themes

The round table at left, with its heavy pot and spray of leaves, answers the sitter like a second subject. The table’s circle echoes the curve of the skirt; the plant’s arabesques repeat the wiggles of hair and neckline. This mirroring stabilizes the composition: the figure is not a solitary island but part of a decorative order that extends into the room. Matisse often arranged such companions around his models—flowers, screens, textiles—not as props but as shaped intervals that let the main motif sit in harmony. Here the pot’s dark ovals and the plant’s darting strokes sharpen the beat of the portrait, preventing the warm wall from turning into formless blaze.

Brushwork that Speaks

Look closely at the black marks. They are not uniform lines but strokes that bear the history of their making. The contour of the skirt presses down and releases in long arcs; the face is drawn with succinct, almost abstract notations for eyes, nose, and mouth; the foliage is a handful of quick, forked swipes that read as leaves because they move like leaves. Throughout, Matisse lets the tool leave its signature—bristle ridges, feathered ends, and a few eager splashes where the brush landed and lifted. This candor is central to the painting’s freshness. We see not only the woman but the tempo at which she was seen.

Light Without Modeling

There is little traditional chiaroscuro. Instead, Matisse stages light as temperature and placement. The dress turns with a pale, cool wash that sits beside warmer notes; the blue floor makes the hem gleam; the red wall enlivens the cheek and hair without resorting to carefully drawn shadows. Even the pot receives a single band of blue and a few dark ovals to declare its volume. The effect is not theatrical light but daylight: an even, benevolent illumination in which color, not cast shadow, does the work.

A Decorative Space That Still Feels Real

The room is not built by linear perspective. Depth is shallow and convincing because of overlap and color hierarchy. The sitter’s arm crosses the skirt; the skirt overlaps the floor patch; the table tucks behind the body; the wall presses forward as an active plane rather than receding as a window. That decorative flattening was Matisse’s lifelong campaign: make the surface sing without turning it into wallpaper. “Marie-José in a Yellow Dress” exemplifies the balance. We accept the scene as a space one could enter, even as we enjoy it as a patterned field.

The Psychology of Poise

Matisse never hunted for psychological drama in faces; he preferred poise and presence. The sitter’s features are abbreviated to a few marks, yet her character reads as alert and self-possessed. Her tilt toward the plant suggests gentle curiosity; the blue object in her hand—a book or folded fabric—hints at quiet occupation. The portrait’s mood is generous: a person at ease in a room set for pleasure. This emotional temperature—calm, bright, unstrained—is the distinctive weather of Matisse’s late interiors.

From Nice Interiors to Late Sheets

The picture belongs to a long lineage that began with the Nice interiors of the 1910s and 1920s, where women in patterned rooms were Matisse’s laboratory for color and line. By 1950 the laboratory results have been absorbed into instinct. The background is no longer a complication of props but a few decisive signs; the model is not elaborately posed but simply seated; the brush no longer fusses with description but says everything in the first pass. At the same time, the picture shares DNA with the 1947 book “Jazz” and the cut-outs that followed: the calligraphic line, the reliance on bold color blocks, and the comfort with large, simple silhouettes.

The Dress as Light Source

The title names the dress, and rightly so. Matisse paints it not as fabric but as light made cloth. The yellow is very pale—more lemon milk than chrome—and it receives stripes of cool wash that read as folds without killing radiance. A hemline scallop and a few vertical bands are enough to give weight. Because the figure is the brightest area in the picture, it behaves like a lamp around which everything else—blue floor, red wall, greenish table—organizes itself. That inversion is typical of Matisse: the subject glows and the world adjusts.

The Role of Blue

Blue is the quiet hero. It anchors three zones—the floor patch, the vase and leaves, and passages behind the sitter’s back—binding them into a spatial triangle. Blue lowers the temperature where the red wall might overheat; it sculpts the pot and tabletop into believable volumes; it slips into the shadowed side of the dress so the yellow stays luminous without turning white. The particular blues—cerulean, ultramarine, a diluted sky—also carry memory. They are Mediterranean blues, the climatic color of Matisse’s later life, and they signal serenity even when used sparingly.

Gesture, Dress, and the Human Scale

The sitter’s stance is modest: hands in the lap, shoulders open, head slightly lifted. The large arcs of skirt and back are scaled to the human body; a viewer can feel the radius of a shoulder’s swing in the contour. That bodily plausibility anchors the stylization. However decorative the room becomes, the figure remains weighty and present, her volume carried by the brush’s curve more than by any devices of perspective.

Editing as Clarity

Part of the painting’s pleasure comes from what Matisse leaves out. There is no fuss over fingers, no texture in the hair, no cast shadow from the pot. He removes everything that does not contribute to balance and mood. The edit lets each surviving mark carry more feeling. A single black crescent at the collar becomes a necklace; two dots and a stroke become eyes and mouth; a trio of slashes suggest leaves. This concentrated vocabulary makes the image legible at a glance and inexhaustible on return visits.

Pattern as Behavior

The red wall is more than a backdrop; it is pattern behaving like nature. Its coral brushstrokes bloom and interlock like a garden seen through lattice. The rhythm quickens near the plant and slows behind the sitter, a subtle choreography that prevents the wall from flattening into a single loud note. In this way, Matisse treats pattern as an active participant—the way a breeze animates curtains or sunlight mottles a floor. Pattern becomes a verb.

The Viewer’s Path

The composition invites a clear journey. The eye lands on the sitter’s face, follows the dark contour down the bodice and around the skirt, crosses the blue floor to the table, climbs through the pot to the leaves, and slips back along the top rail into the upper blue patch before returning to the head. This counter-clockwise loop is reinforced by the placement of color: yellow draws us down; blue carries us across; red pushes us back in. Because the path is circular, the painting sustains attention without demanding it.

A Portrait of the Everyday as Luxury

Matisse’s late interiors propose that everyday life can be a form of luxury if arranged with care—light tuned, objects chosen for shape, color balanced. “Marie-José in a Yellow Dress” embodies that proposal. Nothing in the room is expensive: a small plant, a round table, a dress without embroidery. Yet the arrangement grants them grace. The portrait is not a display of wealth but of attention, the true subject of Matisse’s career.

Resonances with the Cut-Outs

In 1950 Matisse was already deep into the cut-out method, where shapes of painted paper are scissored and pinned into compositions. The logic of those works—flatness, decisive edges, color purity—filters back into this painting. The skirt could almost be a fleece-white cut piece edged with black; the plant’s leaves are cut-out glyphs; the red wall behaves like a single swath of paper overprinted with quick marks. The cross-pollination keeps the brush painting fresh and the cut-outs humane.

Why the Picture Still Feels New

The portrait looks startlingly contemporary because it takes risks that align with today’s design sensibilities: flat color, graphic line, and an absence of fussy detail. Yet it never feels cold. The line is handmade; the washes bloom; small hesitations remain visible. That union of graphic punch and human touch—posters that breathe, logos with pulse—is why late Matisse continues to instruct painters, illustrators, and designers alike.

Conclusion

“Marie-José in a Yellow Dress” compresses Matisse’s mature discoveries into a single, lucid statement. A few colors in flat fields, a calligraphic contour, and a decorative space that remains believable are enough to conjure a person and a room. The model’s presence is felt not through meticulous likeness but through rhythm and poise. The plant, table, and patterned wall are not props but partners in a harmony where color is structure and line is music. It is a portrait of attention—and of the calm happiness that results when looking, hand, and color arrive at the same key.