Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

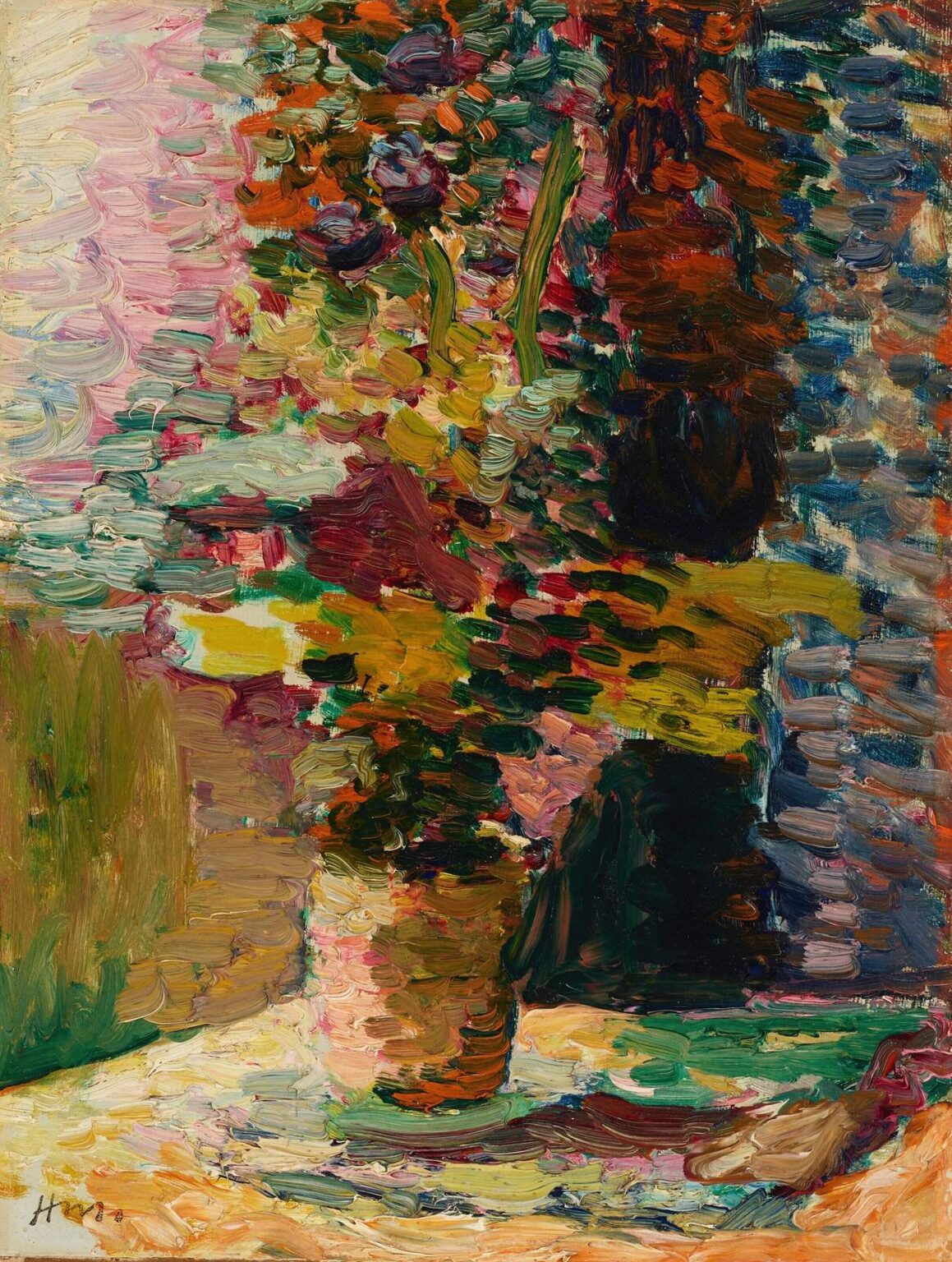

Henri Matisse’s “Vase of Flowers” (1900) looks, at first, like a classic still life: a bouquet gathered in a modest pot set on a small table. Step closer and the painting dissolves into a storm of color. Thick, loaded strokes—greens, violets, hot reds, creamy yellows, smoky blues—pile up like petals of paint. Nothing is outlined; everything is built from short, energetic touches that knit together into form. The bouquet swells upward from a cylindrical vase; to the left the wall ripples in light pinks and mauves; to the right a column of cool blue-grey strokes deepens the room; across the bottom, the tabletop rolls in swaths of butter, mint, and amber. The overall effect is lush and urgent—a young painter testing how far color and impasto alone can carry the illusion of things.

What makes this early canvas so compelling is not just how it looks but what it predicts. Painted at the turn of the century, the work still breathes the air of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, yet the future Matisse—color radical, architect of Fauvism—flares in the saturated palette and the refusal to describe detail. This analysis explores the painting’s structure, touch, palette, and place in Matisse’s development, clarifying why such a compact still life remains a key document for understanding the artist’s rise.

Historical Context: Matisse on the Brink

In 1900, Matisse was in his early thirties, moving beyond academic training and the symbolist encouragement of Gustave Moreau toward a personal language grounded in color. He was studying the example of Monet’s light, Cézanne’s structure, and Van Gogh’s charged stroke while watching the Neo-Impressionists experiment with optical mixtures. “Vase of Flowers” condenses those influences without imitating any one of them. From Impressionism comes the bristling attention to light through broken color; from Cézanne, the insistence on building form through patches rather than contour; from Van Gogh, the conviction that brushwork itself can be expressive. The piece arrives just five years before the blazing revelation of Collioure (1905). Seen with hindsight, it reads like a rehearsal: the palette is already turned high; the description is already subordinated to harmony.

Composition: Centered Mass, Roaming Edges

The composition is disarmingly simple: a vertical vase near the center bottom rises into a large, asymmetrical bouquet. Around this core, three backdrop zones create a subtle tripod of stability. At left, a pale lavender-pink wall is painted in horizontal, scalloped strokes that echo flower petals. At right, a cooler blue-grey vertical field stacks short dabs into a column that feels like a shadowed wall or curtain. Between them, a muted olive plane pushes forward like a screen. The base is a tabletop whose cream, green, and ochre bands curve gently, implying a shallow oval surface. This structure lets the brushwork stay lively—nearly abstract in places—without the painting losing its hold on the still-life genre. We always know where we are: a pot on a table, a bouquet against a wall. Within that frame, Matisse can let paint play.

The Vase: A Modest Anchor

The pot is not a showpiece. It’s a small, cylindrical container articulated with quick, vertical strokes of ochre, rose, and olive, then wrapped in warm, creamy highlights. Matisse keeps it humble so the bouquet can dominate. Yet the pot matters: it gives the eye a point of rest and a measure of scale; it carries reflected color from the surrounding zones, knitting the foreground to the background; and it provides a low, warm counterweight to the cool mass at right. Its very ordinariness is strategic, allowing the brushwork to shift from plane to plane without a jarring change of register.

The Bouquet: Paint Acting Like Petals

The flowers are not catalogued; they’re conjured. Matisse lays in tight, comma-like touches—maroons slipping into violets, sap greens into viridians, cadmium yellows into tangerines. Each dab is both leaf and petal, shadow and light. The bouquet’s architecture rises as a series of chromatic clusters: a darker crown near the top, a mid-zone of citrus yellows, and a lower belt of mixed reds and greens. Two or three long, upright strokes read as stems; the rest is a living mosaic. Seen up close the surface is a topography of impasto; step back and the bouquet coheres as volume, its weight balanced on the small pot like a tree on a stump.

Gesture and Facture: The Hand Made Visible

The painting’s pleasure is inseparable from its facture. Matisse loads the brush heavily and leaves every decision on the surface. You can feel the sweep of his wrist in the thicker ribbons, the quick pecking of the tip in the smaller, rounded touches, and the slight twist where two colors mingle wet-in-wet. There’s scraping and scumbling at the margins where he adjusts edges without outlining them. Because the strokes are neither hidden nor polished away, we experience the still life as a record of looking in time—an accumulation of decisions rather than a single, fixed description.

Light Without Shadows

There’s no conventional shadow model here: no cast silhouette of the vase, no carefully plotted light source. Instead Matisse paints light as temperature and value shifts. Creamy strokes ignite the tabletop; cool blues and greys deepen the right-hand column; lemon and mint flecks light the bouquet from within. The result is a “glow” rather than a spotlight—light as an atmosphere captured by a swarm of color choices. This approach will become a hallmark of Matisse’s mature work: illumination delivered by the key of the palette rather than by the physics of shadow.

Color Architecture: Complementaries at Work

The canvas is a study in complementary play. Red-violet petals press against yellow-green leaves; rose and peach highlights flare against cool blues; earthy ochres steady the whole against creams and mints. These oppositions aren’t arranged like a chart; they appear as naturally as leaves and flowers occurring side by side. Because the complements are set as neighbors, not blends, the eye mixes them optically at a distance—a technique Matisse borrows from the Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist toolkits while keeping his stroke broader and freer. The palette feels both earthy and high-key: pigments are pushed hard but remain grounded by the warm, food-like tones in the vase and cloth.

The Backgrounds: Not Backdrop, but Participants

The left field’s lilac and pink scallops echo the bouquet’s petal rhythm at a lower volume, as if the wall were catching reflected color. The right field’s short, grey-blue dabs feel like cool air or shadow, compressing space and throwing the bouquet forward. The middle olive plane—softly brushed, less impastoed—acts like a neutral zone that prevents the hot bouquet from popping too hard against the pinks. None of these zones is inert. Each contributes a distinct tempo and temperature, and together they “tune” the bouquet to the room. In later decades Matisse will make such fields the protagonists of whole interiors; here we see the idea germinating.

Depth by Overlap, Not Perspective

The paint scarcely acknowledges linear perspective; depth comes from overlap and chromatic hierarchy. The vase overlaps the cloth; the bouquet overlaps the various wall fields; the darkest passages sit farther back; the highest-value strokes glide forward. This is an interior space we believe without measuring. The method frees Matisse to treat the canvas as a surface of interactions rather than as a window that must obey geometry.

Speed and Revisions

Despite its improvisational feel, the painting shows signs of revision. Along the vase’s left edge, softer scumbles suggest a change of outline; in the lower cloth, bands of color have been wiped and repainted, leaving a palimpsest of earlier decisions. These traces do not read as indecision; they add vibration and depth to the surface. The viewer senses both swiftness and care—the flexible rhythm of a painter working until the harmony clicks.

An Early Statement of Matisse’s Priorities

Three commitments—already visible here—will steer Matisse’s career. First, color is structural, not decorative; it builds the scene. Second, drawing can be carried by the brushstroke itself; contour is optional. Third, the decorative field is not the enemy of reality; it is reality understood through harmony. “Vase of Flowers,” modest in subject, broadcasts these priorities with confidence. The later odalisques, Nice interiors, cut-outs, and chapel windows all grow from this soil.

Dialogue with Tradition

Still life is a testing ground in French painting—from Chardin’s sober tables to Cézanne’s assembled apples. Matisse enters the conversation by refusing illusionistic polish and doubling down on paint as matter. He doesn’t abandon the table, the vase, the bouquet; he simply asks them to behave like instruments in a color orchestra. In doing so, he keeps faith with tradition while shifting its emphasis from verisimilitude to sensation.

The Viewer’s Path

The composition guides the eye in a loop. We start at the vase’s warm collar, climb through the yellow band into the dark crown, slide right along the cool blue column, drop into the shadowed base, and sweep left across the creamy cloth before rising again. This circular path mirrors the movement of the brush itself: up into the bouquet, out to the edge, down to the table, and back. The painting becomes a choreography the viewer completes with their gaze.

Materiality and Scale

The canvas’s scale feels intimate—large enough for broad strokes, small enough to read the mark of a single wrist. The paint’s thickness produces tiny reliefs that catch gallery light, changing as you shift position. This material presence matters: Matisse wants you to feel oil as oil, not mistake it for the texture of petals. The tactile “truth” of paint amplifies the visual truth of color.

Senses and Synesthesia

Color and texture trigger other senses. The buttery impasto suggests the weight of cream; yellow-green notes read as the cool wetness of stems; deep maroons hint at flower musk; the cloth’s pale swath feels like sunlight warming a tabletop. Matisse courts these cross-sensations without slipping into literalism. The still life is not a bouquet to sniff; it is a bouquet to see so vividly that the other senses spark on their own.

Why This Early Work Endures

“Vase of Flowers” endures because it condenses a big argument into a small scene. It argues that painting’s power lies not in copying but in composing; not in finishing every part, but in tuning every relation. It proves that a vase, a cloth, a wall—painted frankly—can carry emotion. And it shows the exact point where Matisse leaves behind schoolroom finish to claim the audacity that will define him. The canvas feels alive because it is honest: about color, about the hand, about the decorative as structure.

Practical Takeaways for Viewers

When you stand before the painting, try three ways of looking. First, step close and browse the marks—their direction, load, and speed; you’ll see decisions rather than things. Second, step back until the bouquet “locks,” noting how complements fuse into light. Third, soften your focus to feel the painting’s temperature: the cool right side against the warm left; the hot bouquet against the creamy cloth. You will sense how Matisse composes experience as much as image.

From Here to Fauvism

Within five years Matisse will use even purer blocks of color and stronger oppositions, earning the nickname “wild beast.” The seeds are here: the courage to let red confront green, to let blue stand as shadow, to let a stroke mean leaf and light at once. “Vase of Flowers” is not Fauvism yet, but it makes Fauvism imaginable—a still life already humming with the electricity of what is to come.

Conclusion

“Vase of Flowers” shows a young Henri Matisse discovering that paint handled with conviction can become reality’s equal. Brushstrokes act like petals, color behaves like light, and a familiar tabletop becomes a stage for modern vision. The work is intimate, but it carries a large promise: that harmony—won through tuned color and a living surface—can make even a small bouquet feel inexhaustible.