Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Painting

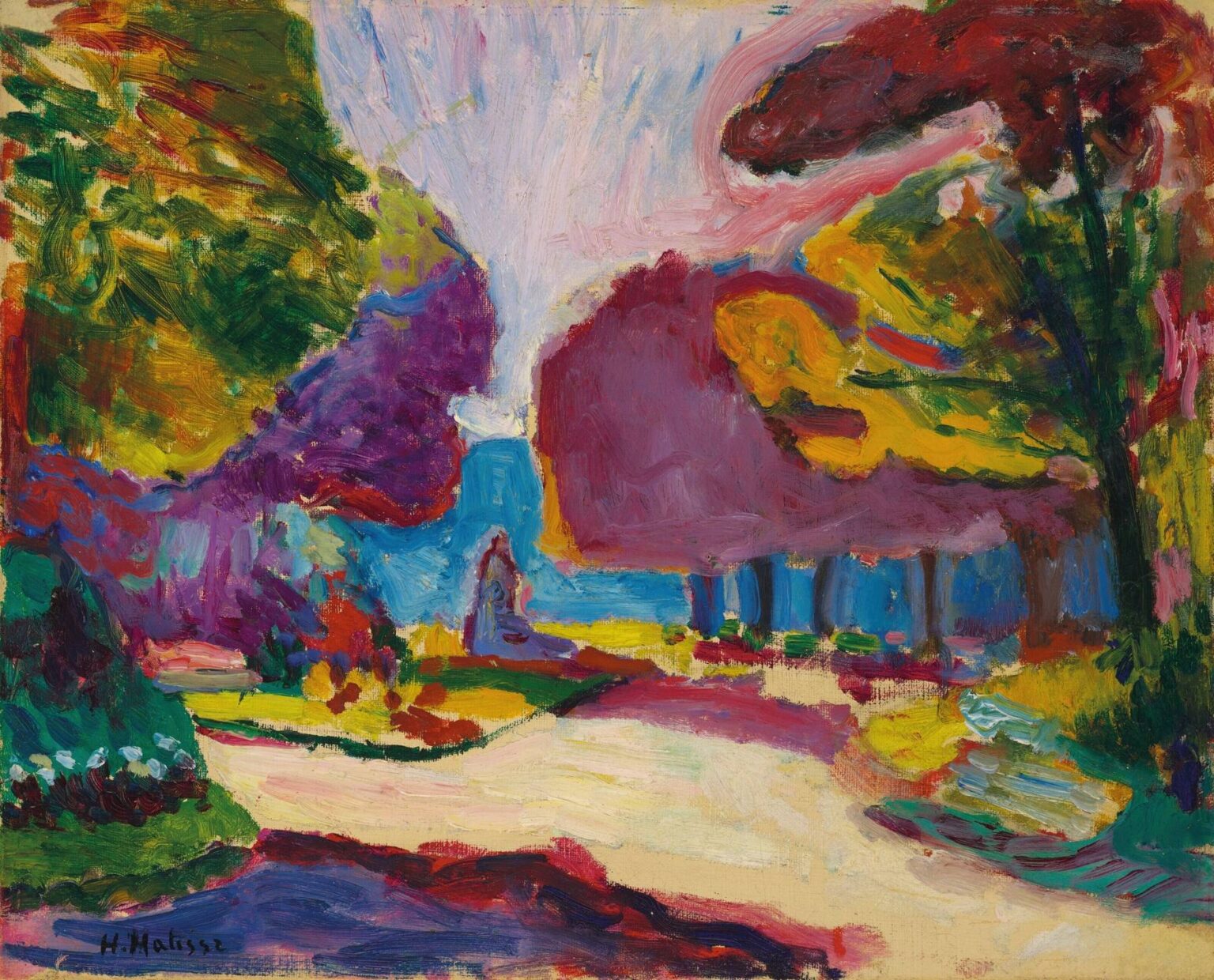

“Luxembourg Gardens, Paris” detonates with color. Trees explode in crimson, violet, and acid yellow; a path sweeps pale and sunlit across the foreground; a vertical shard of cool blue suggests a fountain or basin at the center; and beyond, a band of deeper blue opens toward distance. Henri Matisse turns a familiar Parisian garden into an arena where color, gesture, and light act more strongly than description. The scene is recognizable as the Luxembourg, yet it has been reimagined through a chromatic grammar that makes perception feel newly alive.

Paris, 1902: A Turning Point Before the Breakthrough

The date matters. In 1902 Matisse stood on the ridge just before his famous leap into full Fauvism. He had absorbed the lessons of Gustave Moreau’s studio and studied the liberated color of Van Gogh and Gauguin. He was also looking closely at the Neo-Impressionists, whose high-key palettes and optical mixtures encouraged him to brighten his own. This picture belongs to that crucible. The palette is already daring, the brushwork unrestrained, and the forms simplified into masses; at the same time, the composition still respects a legible space. It is the sound of a door about to swing open.

The Motif and Its Urban Theater

The Luxembourg Gardens offered Matisse a ready-made stage: curving walks, allées of trees, clipped lawns, statues, and fountains. He uses that theater not to catalog details but to orchestrate forces. The light path becomes a proscenium; the dark foreground reads as the orchestra pit; the massed trees form wings at left and right; and the central blue passage is a vertical aperture where air and water gather. The garden is less a park than a set of planes whose collisions create a rhythm.

Composition and the Sweep of Movement

A broad S-curve arcs from the lower left across the foreground and into the middle distance, turning the viewer’s body in sympathy. This sweep is opposed and stabilized by verticals—the fountain’s blue shaft and a rank of dark tree trunks on the right. Large color masses counterpoise each other: a dense green-yellow thicket at left, a violet-magenta canopy near center, a flame of orange-yellow at right crowned by a red-brown bough. The composition is built like a piece of music, with phrases that echo, overlap, and crescendo toward the brilliant opening near the center.

The Path as a River of Light

Matisse paints the path not as dirt but as light itself. Creams, lemon tints, and shell pinks slide together, with violet and carmine surfacing at its edges like undertones. Its paleness opens a breathing space inside the saturated field and directs the eye forward. Because the path is also the largest continuous light value, it behaves as the painting’s reflector, throwing illumination back onto the surrounding colors and intensifying them.

Color as the Subject

In this painting color is not an adjective; it is the noun. Greens are pushed toward emerald and viridian, violets toward amethyst, reds toward cochineal. The combinations are chosen for vibration rather than fidelity to local tone. A purple canopy abuts a band of electric blue; yellow sits next to crimson; deep green is streaked with orange. These are not errors of observation but constructive decisions. The garden becomes a field where complements collide and harmonies are forged, and the eye experiences brightness as sensation rather than reportage.

Complementary Tensions and the Heat of Opposites

The composition leverages complementary pairs with almost architectural precision. Magenta leans into lime; red-brown rides the edge of green; blue slices through orange and yellow. Where complements touch, Matisse often leaves a thin seam of unmixed pigment, allowing each color to keep its identity and making their meeting line flicker. The result is a contained volatility, like static electricity humming along every boundary.

Light as Color, Shadow as Chromatic Shift

There is little traditional modeling. Light arrives as high-value color; shadow is not brown or gray but a shift toward cooler or deeper hues. The trees at right are not dark because light is absent; they are dark because their color has been driven into a lower register of the chosen chord. In the central canopy, violets and wines replace earthy shade, so that even the shadows burn. This approach keeps the surface alive and avoids dead zones.

Brushwork and the Pleasure of Facture

The paint handling is frank, physical, and varied. In foliage Matisse lays down short, curved strokes that interlock like scales; in the path he switches to longer swathes and troweled scrapes that leave the undercolor breathing through; in the sky he feathers pale strokes outward from the center so the light seems to emit rather than merely fall. Edges are often built by the collision of two strokes rather than by a drawn line, and in many places a ridge of impasto catches light, giving the color an extra charge. The surface reads as a record of decisions rather than a polished finish.

Space Between Depth and Plane

Despite the chromatic audacity, the painting still offers a workable space. The path recedes; the trunks on the right align like a colonnade; the blue band beyond suggests a water basin or distant lawn. Yet all of this depth is continuously checked by the flat authority of color. Large masses push forward to the surface and refuse to behave as mere background. Matisse balances this tug-of-war so that the viewer experiences both immersion and frontal impact.

The Central Blue and the Logic of a Fountain

At the painting’s heart a blue vertical expands into a triangular plume of almost white strokes. This could be read as a fountain jet or a shaft of sun piercing between canopies. Either way it functions as the anchor of cool within a hot composition. The blue is neither overly blended nor diffused; it is a declarative note whose placement calibrates every surrounding warm. That verticality also provides a central pause—a breath—within the swirl of lateral movement.

The Figure as Scale and Tempo

Near the blue band a small figure, quickly stated, appears to linger—a passerby or guardian of the basin. The figure is not a narrative protagonist; it is a metric device. Its modest scale confirms the breadth of the space and slows the picture’s tempo the way a human in a landscape slows one’s stride. The same is true of the dotted white flowers at lower left: they register as notes against the larger chords, reminders that the world retains particulars even in the midst of abstraction.

Parisian Garden, Mediterranean Heat

Although the site is Paris, the chromatic climate suggests the heat of the south. Matisse, already dreaming of brighter latitudes, imports a Mediterranean temperature into a northern park. The yellows and reds have the dry bell of southern noon; the blues carry the depth of sea light rather than gray Paris sky. The garden becomes a vessel for a different weather—an imagined radiance imposed on a familiar geometry.

Memory, Invention, and the Decorative Turn

The difference between an on-the-spot sketch and this painting is the work of memory and invention. Matisse remembers the curve of the path, the stand of trees, the fountain’s site, and rebuilds them with an eye to pattern. The picture anticipates his later decorative interiors: large colored fields, repeated rhythms, and a composition that reads both as a place and as an ornament. The garden is not dissolved into wallpaper; rather, it reveals the ornamental order that underlies nature when seen through a simplifying intelligence.

Dialogue with Post-Impressionism

In its high-key palette and assertive surface, the painting converses with Gauguin’s flat color, Van Gogh’s charged stroke, and the Neo-Impressionists’ chromatic clarity—while rejecting their strict systems. Matisse declines pointillist method and symbolic narrative alike. He takes from them the courage to let color carry meaning and then pushes toward a freer, more musical syntax. What emerges is neither anecdote nor theory but a practice of tuning a picture to a key.

Emotional Temperature and the Viewer’s Role

The emotional tone is exuberant yet grounded. Saturated warms generate heat; cool blues and violets moderate it; the pale path holds the scene open. The viewer is invited not to stroll the garden but to inhabit its energy. Because the forms are simplified, one’s imagination supplies sound, scent, and the cool spray of the fountain. The painting becomes a participatory device, a catalyst for sensation.

Material Honesty and the Evidence of Making

Matisse allows underlayers to show, lets strokes overlap without disguise, and leaves small raw patches where the ground peeks through near the path and sky. These decisions keep the painting from sealing itself off. We witness not only a finished image but the process that produced it—adjustments, returns, and kept risks. That honesty makes the color feel earned rather than decorative excess.

Anticipating the Breakthrough to Fauvism

Seen from the vantage of later years, this canvas looks like a prelude. Its fearless complementaries, front-loaded surfaces, and large, coherent masses foreshadow the explosions of 1905. Yet it is also distinct. The composition retains a central anchor, and the space remains readable. In that balance lies the picture’s special pleasure: it lets us feel the exact threshold where observation turns into invention.

Why the Painting Endures

“Luxembourg Gardens, Paris” endures because it turns an everyday public place into an experiment that still feels immediate. The image is both a garden and a chord. It can be read as a walk under trees toward a fountain, or as a tapestry of reds, violets, greens, and yellows stitched together by a pale path. That double readability keeps the picture young; it offers clarity without closing interpretation.

Conclusion: A Garden Rewritten as Color

In this work, Matisse rewrites a Paris garden as a language of color and gesture. Planes replace detail, complements spark along their seams, light is painted as paint, and the viewer’s attention is tuned to rhythm rather than to narrative. The picture does not merely record an afternoon; it constructs one, composed to the pitch of delight. From this ground he would soon take the larger step into Fauvism, but the essentials are already here—courage, clarity, and a belief that color, handled with intelligence, can be a complete way of seeing.