Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Painting

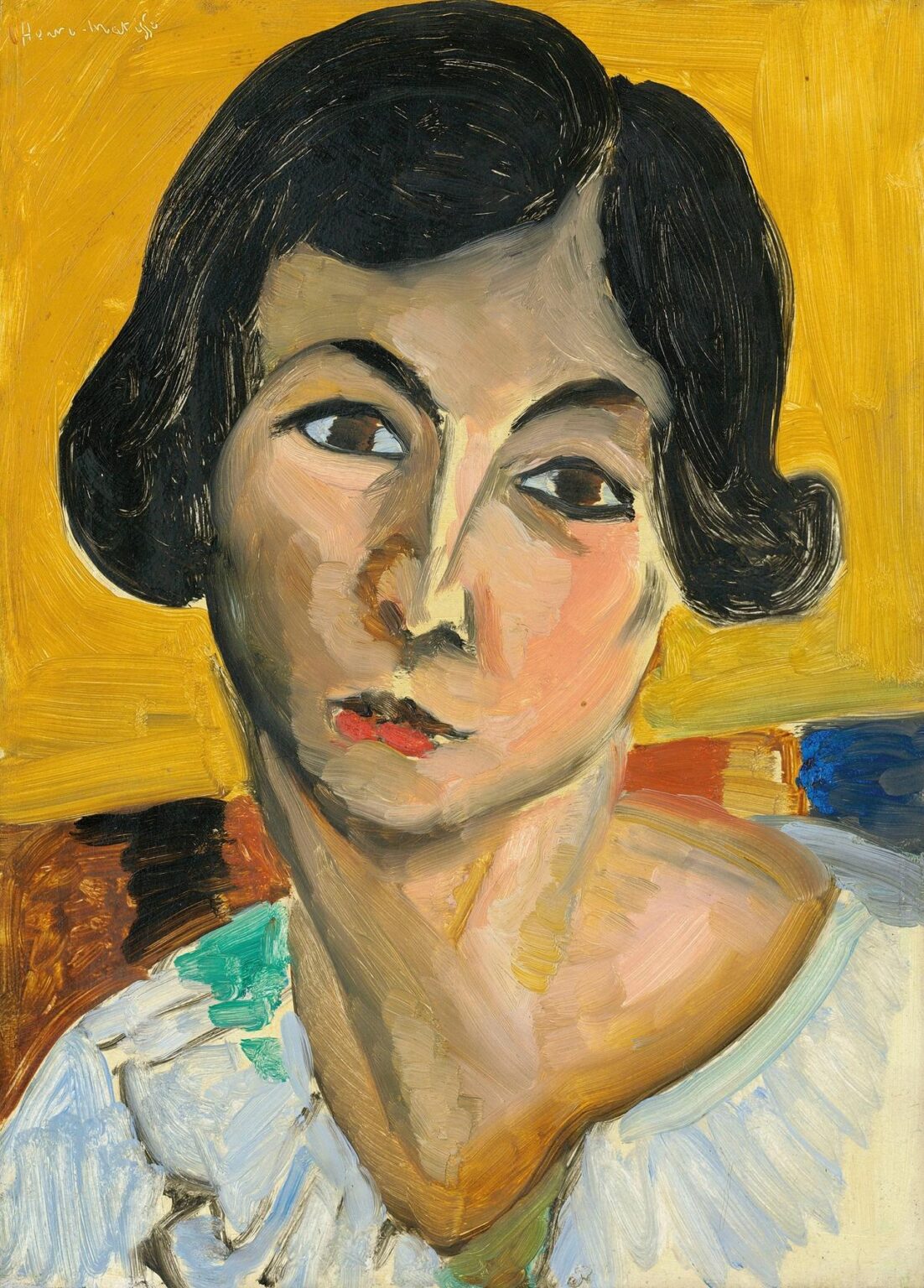

“Head of a Leaning Woman (Lorette)” is an arresting small portrait in which Henri Matisse compresses mood, structure, and color into a tightly cropped bust. The model’s head tilts subtly, her eyes glancing sideways with an awareness that feels private yet unguarded. Broad, decisive strokes define hair, cheek, and neck; the background blazes with a mustard-gold that turns the face into a luminous island. The paint is laid on with confidence, often in single, directional swathes that keep the energy of the hand legible. What first appears simple becomes complex as the eye acclimates to the economy of means. Every mark counts, and every mark participates in a measured orchestration of warm and cool, curve and angle, intimacy and distance.

Lorette and the 1916–1917 Series

The model known as Lorette occupied Matisse’s attention through 1916 and 1917. She appears across dozens of canvases and drawings, sometimes elaborately dressed, sometimes bareheaded, sometimes in interiors dotted with patterned fabrics, sometimes stripped down to an almost sculptural presence. The series was not about anecdote so much as about variations—the way a single face could be reimagined through shifts of palette, costume, and pose. “Head of a Leaning Woman (Lorette)” belongs to this sustained investigation. Its tight framing signals a desire to put aside theatrical surroundings and focus on the working parts of expression: the brows, the tilt of hair, the mouth set in a half-thought, the long wedge of the nose that organizes the planes of the face. The painting presents Lorette not as a personality locked in time but as an instrument through which the painter finds new accords.

A Transitional Moment in Matisse’s Practice

The year 1917 sits at a hinge in Matisse’s career. The early explosive Fauvism had already given way to a decade of experiments in construction and order, and the radiant Nice interiors were just about to begin. This portrait bears traces of both sides. The color’s immediacy, especially the saturated background and the red note of the lips, remembers the Fauve appetite for chromatic assertion. The careful building of planes around the nose and eyes, the calm geometry of the head’s mass, and the measured clarity of the drawing anticipate the later pursuit of serenity. The result is a painting that is modern without aggression, exploratory without losing its poise. It demonstrates how Matisse could simplify a head into a network of decisive shapes while retaining the feel of living presence.

Composition and Cropping

The composition is insistently close. The head fills almost the entire panel, the hair touching or nearly touching the upper edge, the shoulders truncated, the neck rising in a strong column that narrows as it approaches the chin. This scale creates intimacy and concentrates attention on the face’s architecture. The tilt is slight but decisive: it slants the brows and the mouth, introducing a diagonal energy that keeps the stillness from turning static. Behind the head the golden field functions like a backdrop on a small stage. At the lower right, narrow bands of ochre, red, and blue slip into view, as if a cushion or wall stripe had been caught by the edge of the frame; their presence quietly counterweights the hair’s dark mass on the opposite side. Cropping thus becomes a compositional tool: by withholding the full body and trimming the context, Matisse heightens the head’s authority.

The Tilted Head and Expressive Asymmetry

The portrait’s psychology begins with the tilt. A straight head would read as declarative, almost confrontational; a sharply canted head would read as theatrical. Matisse finds a middle register, enough tilt to suggest a transient thought or an inward turn, not enough to sacrifice balance. That inclination ripples through the face’s components. The brows angle unevenly, the left eye rides slightly higher than the right, and the mouth’s red-black shape leans toward one corner. The asymmetries do not contradict likeness; they animate it. They also open a path for the viewer’s gaze to travel, starting at the dark eyebrow arcs, sliding down the ridge of the nose, and pausing at the small red mouth that gathers the painting’s warm hues into a single accent.

Color Architecture: Ground, Flesh, and Accents

Color in this work behaves like architecture. The golden background is not an afterthought but a structural plane that pushes the head forward and stabilizes the palette’s temperature. Matisse modulates the face with restrained flesh notes—peaches, muted olives, pale ochres, and a few cool grays—so that the skin reads as a living surface rather than an academic blend. The black hair and brows anchor the image, providing the deep value that allows the lighter planes to shine. A small shock of red at the lips, tempered by a touch of black, concentrates attention at the face’s center. Greens and turquoise in the blouse act as cool relief, preventing the image from burning too hot; they also set up a complementary chord against the dominant yellows and oranges. The little bar of blue at right is a masterstroke: modest in size but mighty in effect, it keeps the painting’s right side from dissolving into warmth and completes the color equilibrium.

Brushwork and the Grammar of Strokes

Matisse paints here in full view of his medium. Broad bristle strokes track across cheeks and neck in diagonals and curves that echo the head’s geometry. The hair is constructed with sweeping, tar-like strokes whose direction locks the coiffure into its sculptural shape. In the background, flatter horizontal and vertical sweeps calm the surface without making it inert. Crucially, the strokes never dissolve into a mechanical weave; they vary in length, pressure, and load, leaving slight ridges of impasto that catch the light. This visible grammar of strokes contributes to a sense of immediacy. We witness not only the sitter but the act of making, and that dual awareness produces a lively present tense.

Line, Edges, and the Role of Contour

Although the painting is built with paint rather than outlining, contour plays a quiet but decisive role. The nose’s long edge, articulated by a pale highlight on one side and a darker note on the other, acts as the face’s axis. The jawline is sometimes softened into the background and sometimes tightened against the neck’s shadow, a modulation that keeps the head from reading as a cutout. Around the eyes, short dark articulations define lids and pupils, yet Matisse avoids the captive detail that would arrest the painting’s flow. Edges breathe. Where the hair meets the background, tiny halos of warm ground show through, a sign of speed that also reads as light seeping around the head. Such edges make the portrait hover rather than clamp down, maintaining pictorial air.

Light, Shadow, and the Construction of Volume

Light in this portrait is encoded more than observed. Instead of a single descriptive source casting clear shadows, we encounter a pattern of warm and cool that constructs form. Cool grays and muted greens gather in the hollows of the cheek and at the side of the nose, while warmer ochres sit on the cheekbones and forehead. The neck famously bears a series of long, slanting strokes that stand in for anatomical gradation; they are just enough to turn the cylinder without burdening it with detail. The eyes contain the darkest values and thus feel deep, even though the pupils and irises are stated with great economy. The overall effect is of a head illuminated from within, built by the painter’s decisions rather than confined by optical recording.

The Background as Stage and Atmosphere

The golden ground does more than isolate the figure; it sets a key. Its saturation keeps the palette sunlit while the brushwork’s horizontal grain steadies the composition. The warmth suggests an interior suffused with mellow light or a screen placed behind the sitter, but Matisse resists literal description. The background is not a room; it is a field. The faint structural memory of boards or plaster in the strokes adds tactile interest without turning into texture for texture’s sake. Because the ground is strong and consistent, the smallest interruptions—the blue and red bars at right, the darker wedge at left—register as events, giving the painting a quiet rhythm.

The Face as Landscape: Planes and Structure

One of the pleasures of this portrait is watching how Matisse turns the face into a sequence of planes that read almost like a landscape in relief. The brow ridges form two gentle promontories; the nose is a long central ridge; the cheeks step down in terraces of color; the mouth sits in a small valley defined by the chin and philtrum. The logic is sculptural rather than photographic. Planes meet in clean junctions, and transitions are emblematic rather than blended into invisibility. This method clarifies the head’s construction, allowing the viewer to read the form immediately from a distance and to enjoy the painterly workmanship up close.

Emotion and Psychological Presence

Despite the economy of means, the portrait is emotionally charged. The sideways glance suggests alertness, even skepticism, as if the sitter measures the situation silently. The mouth’s asymmetry complicates the expression: one corner lifts, perhaps in the prelude to speech; the red pigment, slightly cooler than the background, brings a living humidity to the lips. The brows’ arc holds the eyes under a mild shadow, intensifying their depth. None of these features is overemphasized; together they add up to what might be called a poised introspection. The painting does not stage drama; it stages a mind at work.

Hair, Clothing, and the Strategic Use of Detail

The hair’s sculpted wave is a marvel of concentration. Matisse carves it with thick, elastic strokes that simultaneously describe volume and establish a strong dark shape to contour the head. The blouse is treated in a different register. Quick notations of white and pale blue suggest fabric without binding the picture to costume description. The small turquoise patch on the shoulder is a crucial cool accent; it freshens the lower quadrant and links the blouse to the blue bar in the background. Detail is thus not distributed evenly but deployed where the painting needs balance or emphasis.

Materiality, Scale, and the Presence of the Hand

Though the subject is a human head, the painting never lets us forget it is paint on a surface. The brush tracks, the occasional ridge of impasto, and the thin, skidding strokes at transitions allow the viewer to reconstruct the sequence of actions. The likely modest size of the support amplifies intimacy; the large strokes relative to scale give the impression of confident shorthand. This material presence contributes to the painting’s truthfulness. Instead of feigning transparency to an illusion, Matisse offers the double pleasure of recognition and facture.

Conversations with Other Lorette Works

Seen alongside other portraits of Lorette, this head emphasizes concentration over ornament. In canvases where the model appears in patterned dresses or amidst interiors, the drama often arises from the negotiation between figure and décor. Here the negotiation happens within the head itself. The same structural nose, the same concentrated mouth, and the same alert eyes recur across the series, but the golden ground and tight crop sharpen their presence. The painting may also be read as a rehearsal for later Nice portraits where color fields stabilize a simplified, emblematic head. It captures the very point at which Matisse recognizes that the fewest elements, properly tuned, can hold the strongest charge.

Relationship to the Portrait Tradition

“Head of a Leaning Woman (Lorette)” speaks to portrait traditions old and new. Its frontality, economy, and insistence on planar construction echo the lessons Matisse drew from icons and early Renaissance heads, where geometry bestows calm. At the same time, the frank brushwork and chromatic simplification align it with modern portrait experiments seeking not to mimic the eye but to grant painting its own law. The sitter’s individuality is respected, yet the painting is not dependent on biographical specificity. It aims at a type of truth that passes through likeness toward presence.

War-Time Interior and the Ethics of Calm

Painted in 1917, the portrait arises in a moment of widespread anxiety. Without narrating that context, the work proposes an alternative tempo. The calm background, the measured strokes, and the intimate scale constitute an ethic of attention. Matisse does not deny the world’s turmoil; he constructs a chamber within it where perception can recover clarity. The portrait’s quiet does not feel escapist. It reads as a disciplined response, a belief that order, however provisional, remains worth making.

Modernity and Timelessness

The painting’s modernity is grounded in its confidence that a few planes and colors can suffice. It refuses fussiness, rejects sentimental finish, and trusts simplified relationships to carry sensation. Yet the result does not age the way novelty often does. The head’s tilt, the golden field, the clipped lips and dark hair—these read as timeless pictorial statements. Part of the work’s enduring appeal lies in this double action: it belongs unmistakably to the studio of the late 1910s and simultaneously to the long conversation of portraiture.

What the Painting Teaches About Looking

To spend time with this canvas is to learn a patient way of seeing. First we register the bold shapes; then we begin to perceive the small veils of color that pass across the cheek, the halation at the hairline, the tiny notch of darker paint that gives the mouth depth. The painting rewards proximity with tactile pleasures and distance with clarity. It demonstrates that attention is amplified by restraint. Because the picture offers no superfluous incident, every incident that remains becomes meaningful. The experience is not one of deciphering a code but of aligning oneself with the painter’s measured tempo.

Conclusion: Concentrated Presence

“Head of a Leaning Woman (Lorette)” distills Matisse’s concerns at a pivotal moment: the search for calm structure after years of upheaval, the affirmation of color as architecture, the belief that a portrait can live through essential shapes animated by frank brushwork. The tilted head feels both emblematic and specific, an image of a person and an image of looking itself. Within a modest frame, Matisse constructs a complete world—one whose warmth, clarity, and concentration continue to hold the eye and steady the mind.