Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Painting

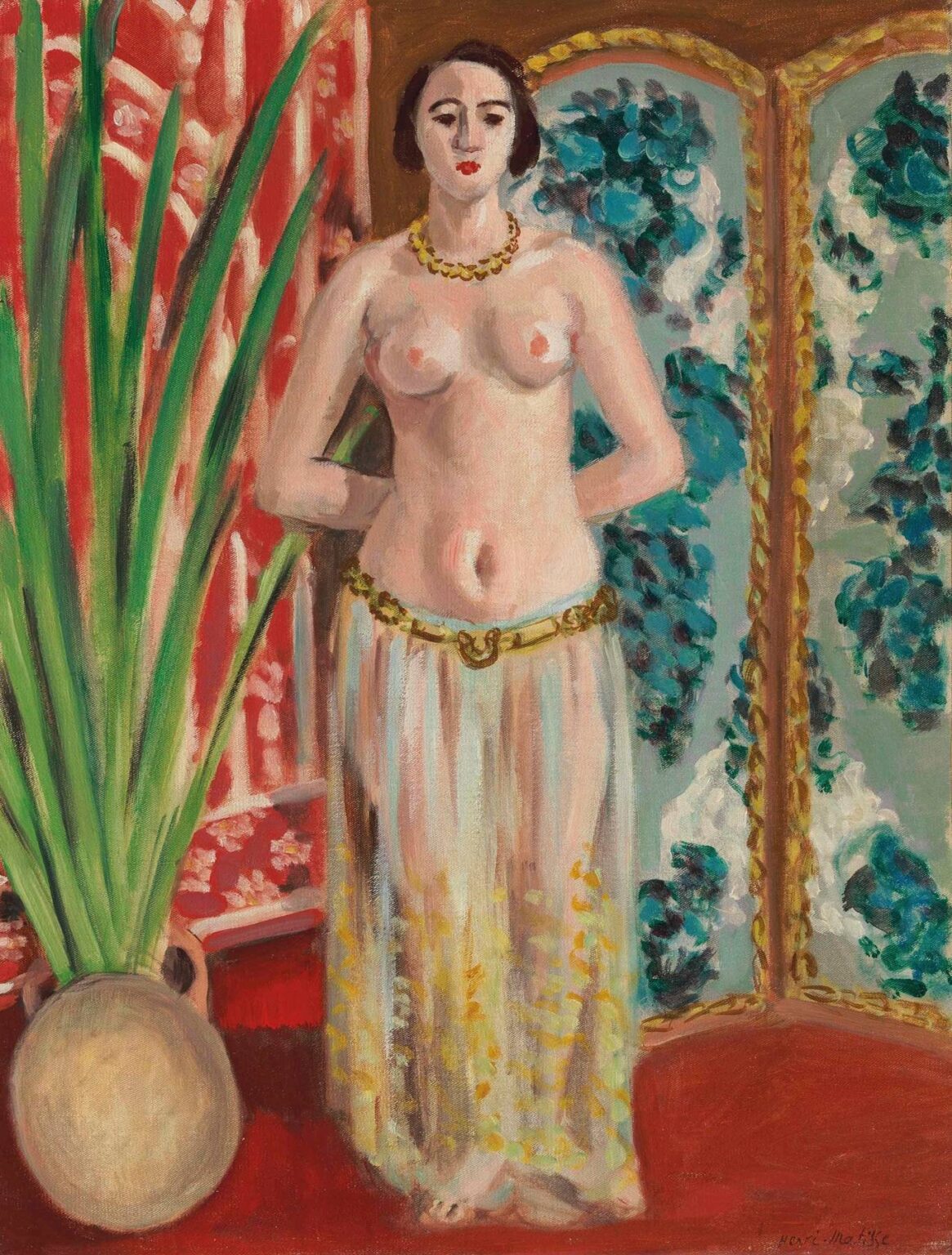

“Odalisque, Hands Behind the Back” condenses Henri Matisse’s Nice-period vision into a compact theater of color, pattern, and poise. A half-nude model stands frontally on a red floor, her hands clasped behind her back, a gold necklace at her throat and a belt glinting at her hips. A gauzy skirt drops from the belt in translucent veils that leave the abdomen and breasts bare. To the left rises a pot of long green leaves; behind her, a folding screen painted with blue blossoms and gold edging holds the wall, while a red patterned textile streams down the far left. The room is simple, but its surfaces are charged. Everywhere that Matisse places a color or a contour he also places an invitation to look more slowly.

Historical Context: Matisse in Nice, 1923

The year 1923 finds Matisse well settled into his Nice routine, away from the disruptions of the war and eager to find a language of calm radiance. In these years he revisited the odalisque theme repeatedly, not as ethnographic report but as a studio fiction that allowed him to orchestrate textiles, screens, cushions, and bodies as instruments in a single decorative ensemble. He sought a balance between the freedom of his earlier Fauvist color and a renewed respect for poise and clarity. The Nice period does not renounce modernism; it reorients it toward serenity. “Odalisque, Hands Behind the Back” shows that purpose with unusual succinctness. The canvas is neither sprawling nor crowded. It is a chamber piece in which every element has its voice.

The Odalisque as Studio Fiction

Historically the odalisque belongs to European fantasies of the harem, but in Matisse’s studio it becomes a formal device. The turban, necklace, belt, and transparent skirt are theatrical cues rather than ethnographic claims. They create a costume that justifies juxtaposing bare skin with rich pattern. The point is not narrative exoticism but the license to stage harmonies of red, blue, gold, and flesh. The odalisque motif thus frees Matisse to fuse figure and décor without apology. By placing the model upright rather than reclining, he further departs from the canonical couch odalisque. The standing posture emphasizes dignity and sculptural presence while preserving the sensuous aura that the theme guarantees.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition stabilizes around a vertical axis that runs from the model’s head through the navel to the gap between her feet. This axial steadiness allows the flanking elements to flare more freely. To the left, the pot with tall leaves shoots an oblique counter-movement upward; to the right, the hinged screen folds gently back, its diagonals opening the wall like wings. The red ground, continuous with the red textile on the wall, forms a chromatic basin that gathers the picture’s energy. The viewer’s eye first meets the figure, then tracks outward along the gold necklace to the plant and along the gold belt to the screen. Because the hands are tucked behind the back, the torso reads as an uninterrupted field of curves—rib cage, belly, and hips—punctuated by the necklace and belt. This simplification of gesture intensifies the role of color and pattern in defining space.

Color Orchestration and the Rule of Red

Red is the canvas’s ruling temperature. It blazes across the floor and blooms again on the fabric that climbs the wall. The intensity of this red requires careful companions. Matisse answers it with the cool, mottled blues and greens of the screen and the plant, creating a complementary field in which each hue heightens the other. Flesh tones—peach, rose, and muted gray—mediate between the poles. The small, repeated notes of gold at neck and hips act like cymbal strikes that keep time within the larger chords of red and blue. The distribution of color is not uniform but strategic: the warm floor locks our gaze to earth while the cool screen breathes air into the background, allowing the figure to stand forward with clarity.

Drawing, Contour, and Structure

The figure is built by line as much as by paint. Matisse’s contours are firm but elastic: the jaw and shoulders are drawn with decisiveness; the belly and skirt with a gentler, searching hand. The breasts are modeled with swift, confident ovals, their edges softened so that they belong to the body rather than sit on it. Around the plant, the brush switches to long vertical strokes that flare at the tips to suggest leaf volume without laboring over botanical detail. In the screen, dabs and commas of blue create blossoms that cohere only at a distance. Everywhere the line refuses pedantry. It asserts the essential curve, confirms the essential edge, and leaves the rest to the eye.

Light and the Sheer Veil of the Skirt

Light in this painting is not theatrical; it is a condition. We feel it most clearly in the skirt, whose thin whites and pale yellows let the red of the floor and the warm of the legs whisper through. A few blue-gray shadows under the belly and at the inner thighs are enough to declare the body’s roundness. Highlights along the necklace and belt glint to confirm the material difference between skin and ornament. Matisse’s restraint with shadow preserves the painting’s decorative plane while still granting the figure sculptural presence. The transparency of the skirt becomes a subtle demonstration of painterly intelligence: color operates as light, and light as color.

Pattern as Architecture

The screen’s blue flowers and the wall textile’s red arabesques are not mere decoration; they are architectural devices that build the room’s depth and rhythm. The screen’s gold frame sets a clear boundary, and its angled hinge creates a shallow spatial recess. The red textile at left presses forward, flattening the wall and pushing the figure toward us. Matisse uses these patterned fields the way a composer uses accompaniment—sometimes supportive, sometimes contrapuntal, always in relation to the lead voice of the figure. The green leaves supply a vertical accent that cuts through the field of reds and blues, a necessary fresh note that prevents chromatic monotony.

The Gesture of the Hands and the Mask of the Face

Because the hands are hidden, the figure’s expressiveness must rely on posture and face. Standing with feet slightly apart, shoulders squared, and chin lifted, she presents herself openly, even ceremonially. The clasped hands likely draw the shoulder blades together, which subtly lifts the chest and lengthens the torso. The face, small yet insistently frontal, is simplified to a few planes and features: dark hair framing the forehead, almond eyes, a straight nose, and red lips. It reads like a mask, not because it is opaque but because it is emblematic. The neutrality of expression allows the color to carry the emotion and the posture to carry the authority.

Sensuality as Measure, Not Excess

The painting’s sensuality rests on measure. Skin is warm but not slick; curves are generous but not exaggerated. The gold belt sits on the hips like a cadence at the end of a musical phrase—an emphasis that completes rather than overwhelms. The sheer skirt courts eroticism but also introduces modesty through its veil. Matisse refuses the binary of prudishness and provocation. He composes a sensual field whose elegance is inseparable from its structure. One senses that the model is comfortable, that the room’s beauty is a shared condition rather than a gaze imposed upon her.

Economy of Means and Painterly Speed

The surface shows evidence of quick decisions honored as final. The plant’s leaves are executed in a few confident sweeps. The blossoms on the screen are clusters of strokes whose edges remain visible, their underpainting peeking through. The red ground is laid broadly, then modulated with darker and lighter swaths to avoid deadness. This economy does not signal haste but efficiency. Matisse chooses the shortest path that preserves vitality. The viewer perceives both the immediacy of the hand and the calm of the result, a rare compound of energy and repose.

Dialogue with Tradition

Standing odalisques are rarer in nineteenth-century precedent than their reclining sisters, but echoes still sound—from Ingres’s exoticized nudes to Delacroix’s Moroccan scenes. Matisse inherits the permission these images granted to merge decorative splendor with the nude, yet he strips away anecdote. There is no narrative pretext, no architectural specificity beyond screens and textiles, no assertion of elsewhere beyond the studio’s theater of patterns. If the tradition sought to transport the viewer to a fantasy harem, Matisse seeks to transport the viewer to painting itself—to the place where color plays roles and lines set the stage.

The Nice Period’s Ethics of Pleasure

Pleasure in these interiors is not an evasion but an ethic. After years of turmoil across Europe, Matisse proposed that clarity, comfort, and beauty could be earnest aims. The odalisque theme gave him a laboratory for working those aims into paint. The works do not apologize for delight; they refine it. In “Odalisque, Hands Behind the Back,” the refinement shows in the restraint of palette, the equilibrium of decoration and form, and the quiet dignity of the model’s stance. Pleasure is shaped, balanced, and offered as a complete aesthetic experience.

Psychological Distance and Viewer Position

The frontal pose and the symmetrical placement place the viewer as a respectful interlocutor rather than a covert observer. We are not peeking into a private boudoir; we are admitted to a staged encounter. The model looks out without imploring or rejecting. The hands behind the back close the body’s gesture inward, reducing any sense of invitation and strengthening a sense of self-contained presence. This distance is paradoxically intimate. We see plainly and we are seen, but a decorous margin is maintained, the same margin that separates painting from life and makes contemplation possible.

Materiality and the Craft of Edges

Edges do much of the painting’s quiet work. Where the red ground meets the skirt, Matisse softens the boundary so the color seems to breathe through the gauze. Where the figure meets the screen, he sharpens the outline to keep the body forward. Around the leaves, he allows small halos of ground to remain, an effect of speed that also reads as light bleed. These craft choices guide the eye without fanfare. They reveal a painter who trusts that the smallest adjustments—thickening a contour, letting a red underglow through a white veil—can carry entire emotional weights.

Comparisons with Other Odalisques

Compared with the more luxuriant odalisques sprawled across couches and daybeds, this upright version is spare. The floor is not strewn with props; the textiles are limited to two zones; the model’s jewelry is minimal. That spareness makes the picture feel almost emblematic, a condensed statement of the theme’s essentials: skin, pattern, and poise. In some near contemporaries, Matisse multiplies patterns to dazzling density; here he concentrates them, heightening each one’s structural role. The result is a canvas that reads quickly at a distance and deepens under close attention.

Modernity Without Aggression

The painting is modern not because it breaks decorum but because it redefines it. Flattened space, deliberate patterning, color as architecture, and visible brushwork all refuse academic illusionism. Yet nothing is abrasive. Modernity here is a calm conviction that painting can be an independent order with its own rules of harmony. In this sense, “Odalisque, Hands Behind the Back” offers a useful counterpoint to the vanguard of the early 1920s, which often equated innovation with fracture. Matisse’s innovation is synthesis: disparate sensations—red heat, blue coolness, gold sparkle, skin warmth—brought to equilibrium.

What the Painting Teaches About Looking

To linger with this canvas is to discover how attentiveness transforms simplicity into richness. At first glance one sees a figure against décor. With time, the décor reveals itself as a system of gentle forces that stabilize the figure; the figure reveals herself as a sequence of curvatures that rhyme with leaves and blossoms; the color fields reveal their micro-variegations, from the brownish blush under the navel to the flickers of citron in the skirt hem. The painting trains the eye to respect small changes and to accept that clarity can be as engaging as complexity.

Legacy and Continuing Appeal

“Odalisque, Hands Behind the Back” continues to speak because it gives shape to a universal human wish: to experience calm without dullness. The poised figure, the steady frontality, the measured hues—all offer assurance. At the same time, the visible stroke, the vibrating patterns, and the ombré transitions maintain liveliness. Viewers return to it not to decode a story but to recalibrate their senses. In that recalibration lies the legacy of Matisse’s Nice period and of this painting in particular: a demonstration that painting can construct a pocket of order in which the eye and mind find rest.

Conclusion: The Elegance of Composure

The canvas stages an encounter between a self-possessed body and a room tuned to receive it. Nothing in it is accidental. Red sets the tone; blue and green cool it; gold punctuates; line clarifies; pattern supports; transparency breathes. The hands behind the back gather the body’s energies inward so that color and posture can project outward. In a few square feet, Matisse articulates an ethic of composure, proof that modern painting can be both sensuous and exact, hospitable and rigorous. “Odalisque, Hands Behind the Back” is not a spectacle but a sustained chord—one that continues to resonate long after the first glance.