Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

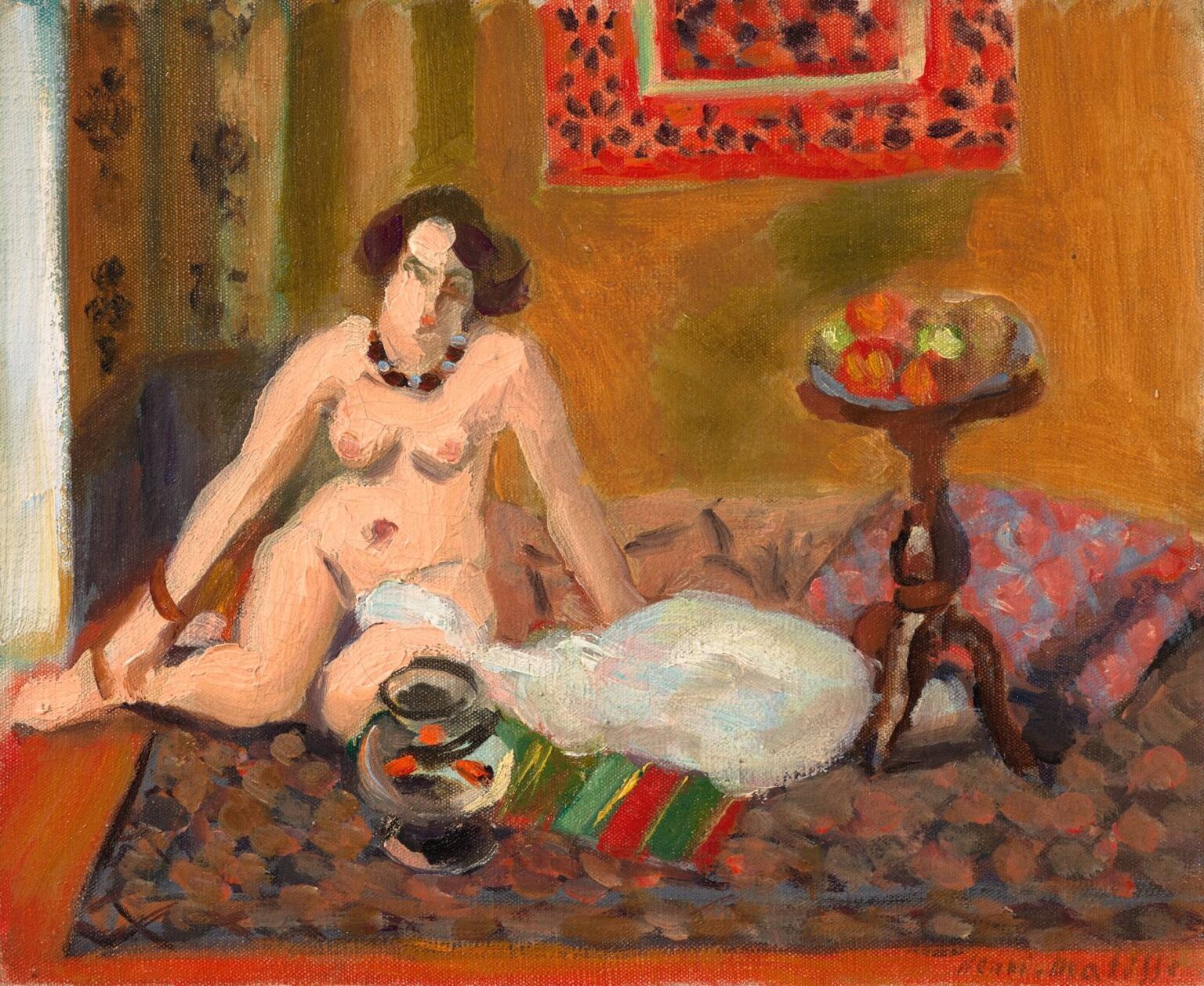

Henri Matisse’s “Nude sitting near an aquarium (Nude with goldfish)” from 1922 compresses an entire world of sensations into a small, intimate interior. A woman sits at ease on layered carpets and cushions; to her left a round glass bowl holds bright flecks of goldfish; to her right a pedestal table supports a heaped dish of fruit; above her hangs a patterned textile that doubles as a window into pure ornament. The ochre wall, the scarlet edge of a rug, the purple-blue drapery, and the rough arabesque of a dark ceramic jar give the room its pulse. This is the Nice period distilled: a nude not as spectacle but as center of gravity, surrounded by objects tuned to the same key. The painting is less a portrait than an orchestration in which figure, pattern, and still life sing the same song.

A Nude Reimagined In The Nice Period

By 1922 Matisse was deep into his Nice years, a long chapter in which he rediscovered the pleasures of interiors, models, textiles, and measured light. The odalisque theme—women at leisure in rooms thick with pattern—became his laboratory for rebalancing color and structure after the radical experiments of the 1910s. “Nude sitting near an aquarium” belongs to this arc. Rather than rebel against the long tradition of the reclining or seated nude, Matisse renovates it from within. He rejects academic finish in favor of broad, frank brushwork; he trades studio theatricality for household intimacy; he lets ornament be architecture. The result is neither an academic study nor an exotic fantasy, but a modern domestic oasis where color does the heavy lifting.

The Goldfish Motif Returns

Goldfish were one of Matisse’s touchstones. A decade earlier he painted them as the entire subject—bright, suspended commas in a cylinder of water that became a miniature stage for pure color and calm. Here the motif returns, no longer sovereign but essential. The bowl’s curve anchors the lower foreground; sparks of orange dart within the dark water; a few reflections kiss the glass; a green-and-red striped book or textile slides beneath it like a visual pedestal. The fish animate the still life without noise. They also rhyme with the fruit on the pedestal table—round, edible, luminous spheres—so that water and table speak to each other. In a room built of fabrics and flesh, these little swimmers are a breath of moving light.

Composition: A Triad Of Figure, Fish, And Fruit

The scheme is triangular and stable. The nude, sitting slightly off center, leans back on one arm while the legs bend in an easy zigzag. Her body forms the left side of a triangle whose other vertices are the aquarium and the fruit dish. That triad distributes attention without scattering it. The viewer’s eye travels comfortably from the figure’s head and necklace to the round jar and fishbowl, then upward to the fruit and back to the face. The carpet’s dark disks and the hanging textile’s red spots repeat the circular theme, knitting the whole field together.

Figure As Climate

Matisse paints the model not as an isolated object but as the climate of the room. Flesh tones are warm but restrained—pinks, peaches, and small islands of cool gray for shadow. He articulates the torso and limbs with large, confident planes, letting a single value change turn the abdomen or thigh. The head is simplified into clear planes around the eyes, nose, and mouth; a short necklace punctuates the neck and echoes the fruit’s small orbs. At the wrist a bangle repeats the ceramic jar’s dark ring. Nothing is labored; clarity does the work of detail. The figure could almost be a piece of furniture, not to diminish her but to show that in this interior human and object share a common order.

Pattern As Architecture

No walls or windows are necessary when textile can do the job. The lower carpet’s tessellated disks, the upper hanging’s red-speckled field, and the squarish cushion of mauves and blues do more than decorate; they define space. The carpet is the floor, the hanging is the wall, the cushion is a bench. Because patterns flatten the surface, depth is created by overlaps and shifts of scale rather than by converging lines. The decorative field behind the model gently tilts, the wall is an ochre plane, and the pedestal’s stem pierces them with a firm vertical. Matisse’s rooms feel habitable precisely because their architecture is rhythmic rather than geometric.

Color Architecture: Warm Ochres And Cool Accents

The painting’s climate is set by the ochre walls and the red-orange edges of the rug—warm hues that bring the foreground forward. Against this heat Matisse places cool notes that tether the composition: the violet-blue cushion, the pale green stripe beneath the fishbowl, the faint opal of the cloth heaped beside the figure, and the subtle gray in the shadows of flesh. The palette is neither Fauvist explosion nor dull naturalism. It is a tuned system in which warmth carries hospitality and cools hold the room open. The green inside the fruit, the orange of the fish, the blue touch in the cushion—each is a strategic instrument in the chord.

The Role Of Black And Earth

Earth colors and near-blacks provide the painting’s bass line. The ceramic jar’s body, the table’s sculpted stem, the scattered darks in the carpet, and the hair framing the model’s face keep the warm ochres from floating away. Matisse was always careful to seat bright colors on darker notes; here the near-black is never dead. It holds brush texture, reflecting light like velvet. Because the darkest tones are textured, they remain alive and contribute to the living surface.

The Fruit Stand: A Vertical Counterpoint

If the fishbowl is a low, watery counterpoint to the nude, the fruit stand is its vertical partner. The small table’s turned pedestal and the plate of rounded fruit establish an upward energy that keeps the composition from sliding into the foreground. The stand also pushes the eye back into the space that the cushion suggests. Its upper disk introduces a small horizon line just beneath the hanging textile; that slight spatial cue is enough to tell us the room has depth without a single vanishing point.

Touch And Material Candor

One reason the interior feels relaxed is that the paint handling is candid. The brushstrokes on the wall are visible, the carpet is handled in dots and commas, and the hanging’s edge is laid with quick, confident lines. Flesh is constructed in broad, warm planes, with a few sharper accents at the elbow, breast, and knees. Matisse does not fuss over transitions; he composes them. Where many painters would have filled every space, he leaves a few areas semi-raw so the canvas can breathe. That breath is the painting’s time signature: we sense the model’s repose and the painter’s steady, unhurried hand.

Ornament And The Ethics Of Pleasure

Critics sometimes mistake these Nice interiors for decoration in the pejorative sense. In fact, they embody a disciplined ethic of pleasure. Pattern is not sugar; it’s the grammar that permits calm. The repeated circles in carpet and fruit organize the field; the bands of color under the fishbowl stabilize the lower edge; the hanging’s frame contains the upper third. Every decorative decision carries a structural consequence. Pleasure here is not indulgence but order you can feel in your body, like a well-tuned musical ensemble.

The Nude As Participant, Not Muse

One of the subtle shifts Matisse achieves in this period is to let the model belong to the room instead of being its spectacle. The woman looks down and inward; her posture is relaxed but alive; she is neither coy nor confrontational. The bangle at the wrist, the necklace, the soft hair, and the easy bend of the knees all speak of comfort rather than display. She is not trapped by the gaze. She is part of the climate that the painter is composing, and the painting respects her presence by letting her be at ease.

Echoes Of Travel And Memory

The patterned hanging and the coppery wall inevitably recall the North African and Middle Eastern textiles that fascinated Matisse during his travels earlier in the century. Rather than quote a specific source or degrade the object into a mere sign of the exotic, he abstracts what he loves: the shallow space, the intense yet contained color, the way ornament can stand in for architecture. The aquarium itself, a domestic vessel of a portable nature, becomes a reminder that the faraway can live quietly in a room at hand.

Light Measured, Not Dramatic

The light in the painting does not descend from a single source. It is embedded in the color relations themselves. Warm ochre acts as light against the cooler carpet; a pale ridge of paint on the thigh becomes a highlight because it meets a slightly darker plane beside it; the fish glow because their orange is set against a deep gray-green. This measured light avoids theatre in favor of clarity. The room glows rather than glares.

Scale And Intimacy

Everything about the image argues for intimacy—the close cropping, the way the bowl and jar approach the very bottom edge, the low angle that puts the viewer on the carpet with the model. Even the hanging textile has been cropped to a square so that it behaves like another participant in the room rather than a distant mural. That closeness makes the painting feel habitable. You don’t stand before it as at a spectacle; you sit with it like company.

Movement Without Motion

Although the model is still, the painting is not static. The circular motifs quietly rotate; the fish circle within their bowl; the painted weave of the carpet encourages a subtle drift of the eye; the fruit’s rounded profiles turn. The viewer’s gaze never hits a wall; it moves in looping paths among round forms and returns to the face. This is how Matisse sustains looking. Movement is designed into the relations of shapes rather than into action.

From Odalisque To Living Room

Compared with later, more elaborate Nice interiors, “Nude sitting near an aquarium” is modest in its props. Its economy sharpens our sense of what matters to Matisse: a human presence, a few rhythmic objects, a strong wall of color, and a carpet that can carry movement. He reduces the odalisque fantasy to the bones of a good room. That reduction is not a retreat; it is the foundation of the amplitude he will later unfold with screens, tapestries, and mirrors. Here we have the essential sentence; later he writes the novel.

What The Painting Teaches

For painters and designers, the canvas is a practical manual. Let a few shapes do the work and repeat their echoes across the field. Use warm grounds to house a figure, and drop cool counters in strategic places to release the air. Treat pattern as a structural device, not as embellishment. Accept visible touch as part of the room’s voice. And, if you want a painting to feel inhabited, give viewers a place to sit—an area of carpet, a low horizon, a table edge—so they can imagine occupying the scene.

Conclusion

“Nude sitting near an aquarium (Nude with goldfish)” is a gentle summit of Matisse’s art of domestic harmony. It turns an everyday arrangement—woman, carpet, bowl, fruit—into a complete ecosystem where color is climate, pattern is architecture, and objects are companions. The goldfish do not merely decorate; they speak to fruit and flesh, turning the still room into a living circuit of rounded light. The painting shows how, in 1922, Matisse’s pursuit of “balance, purity, and calm” was not an escape from modern life but a way of organizing it—room by room, color by color, until a viewer could step in, breathe, and stay.