Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

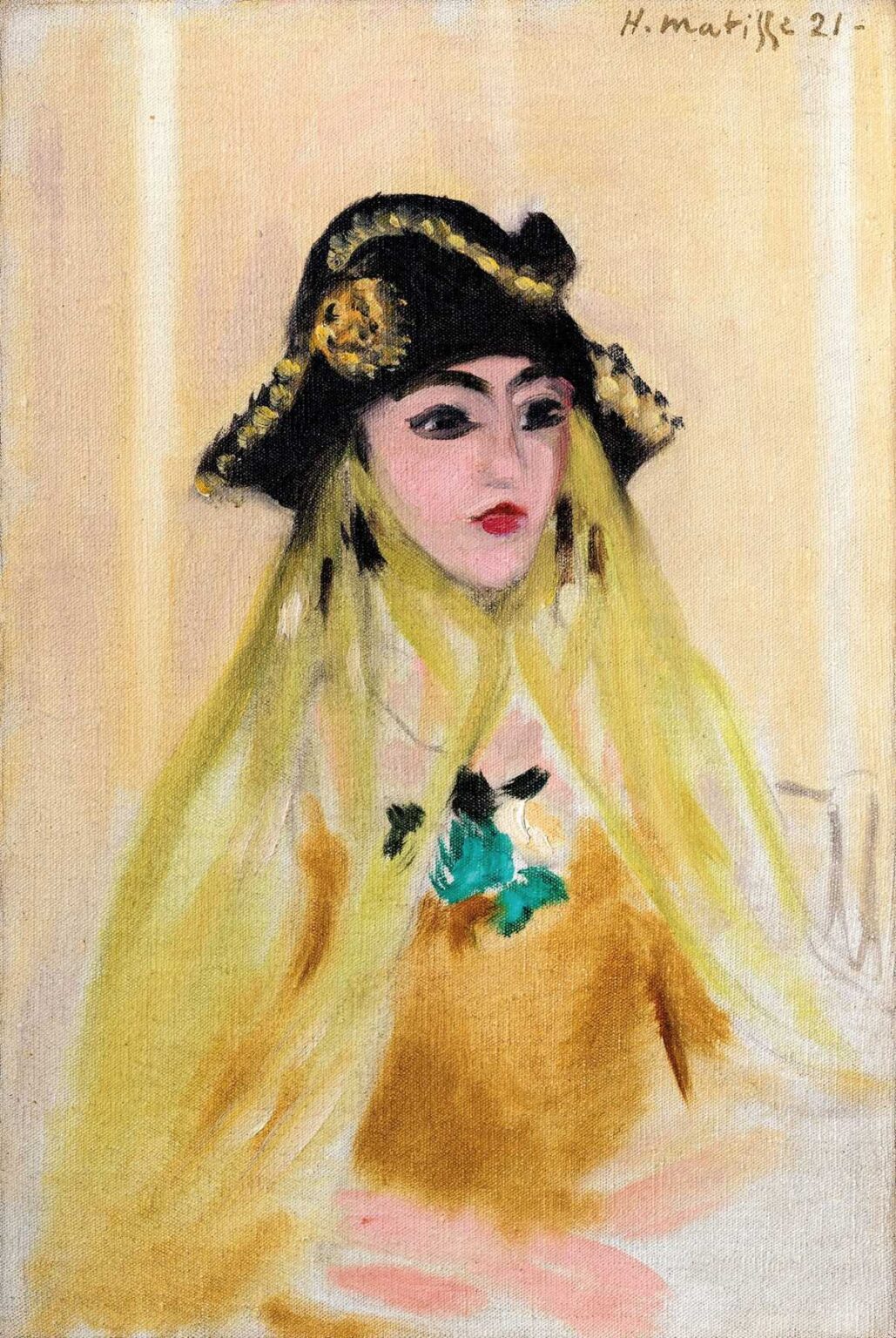

Henri Matisse’s “Ancilla” (1921) is a compact, radiant demonstration of how the artist could distill a portrait to its most telling relations of color and edge. A young woman in a dark hat trimmed with gold faces us three-quarters, her red mouth and arched brows set within a masklike oval. Long, lemon-blond strokes cascade over her shoulders like a shawl of light. A quick turquoise flourish at the neckline jolts the warm harmony, while the creamy background, barely articulated, lets the figure bloom forward. The canvas feels spontaneous, even improvised, yet its informality is the result of a veteran painter’s ruthless selectivity. In this small painting, Matisse turns costume, complexion, and background into one orchestration that describes presence without heavy detail.

The Nice Period And Why 1921 Matters

Matisse had settled into the Mediterranean rhythm of Nice by the early 1920s. Sun-struck interiors, patterned floors, screens, and models in robes or hats provided a steady vocabulary. The heat and shock of Fauvism were behind him; in their place came a classical ease—clean drawing, luminous color, and a preference for shallow, decorative space. “Ancilla” sits near the beginning of that maturity. Its scale and sketchlike directness align with the small, nimble portraits Matisse made between larger interiors, using them as laboratories to test how little was needed to conjure a person. The painting condenses the Nice ethos: intimacy, theatrical accessories, and color that acts as climate rather than costume.

First Impressions And Reading Path

At first glance the eye lands on the hat: a dark, tricorne-like shape capped with gold medallions. From that bold silhouette, attention drops to the face—pale, oval, decisively drawn eyes and brows, a mouth in a clean crimson note. Then the gaze spills into the yellow cascade of hair and the tawny garment, pausing at the cool turquoise knot near the chest before dissolving into the light field of the background. The route is deliberately simple. Matisse sets one high-contrast element (the hat) to hook the eye, one warm field (hair and dress) to sustain it, and a cool accent (turquoise) to keep the harmony from closing in on itself.

Color As Climate

The palette is spare but strategic. Creamy beige, honeyed yellow, and tawny ochre build a warm atmosphere that supports the complexion and hair. Against that warmth, the deep black of the hat does more than describe a material; it sets the pitch of the painting, a bass note that makes the surrounding colors ring. Gold touches laced through the hat flicker like sunlight and connect to the skin’s warmer notes. The turquoise bow or corsage is the single cool chord. It jolts the harmony, prevents monotony, and subtly echoes the hat’s ornament by offering a different kind of brightness—light through water rather than light across metal. Because values stay mostly mid-range, temperature carries the picture’s structure: heat gathers at the center; a refreshing cool interrupts it; the blacks frame and stabilize.

The Hat As Stage And Frame

Matisse often used headgear not as ethnographic detail but as a device to stage a face. Here the hat functions as a portable proscenium. Its crisp edges articulate the top and sides of the head, while its gold rosettes supply punctuation that echoes the sitter’s jewelry in other Nice portraits. The hat’s dark mass also makes the cheek and forehead luminous by contrast; the face appears to light up simply because it is placed under a dark canopy. By keeping the hat’s form simple—two or three decisive arcs—Matisse lets it behave like a graphic frame. It is not a still-life object perched on the sitter; it is architecture for the portrait.

The Face Between Mask And Presence

The facial description is minimal: heavy, arched brows; almond eyes set with a few black strokes; a straight nose described by a single shadow; a small, emphatic red mouth. The simplicity pushes the head toward a mask, but not a cold one. Subtle shifts in pink and beige on the cheeks and chin, and a slight retreat into gray at the eye sockets, keep the face alive. The balance is delicate and intentional. Matisse refuses fussy modeling because he wants the head to coexist with the decorative order of hat, hair, and background. Yet he grants just enough interior modulation for the viewer to meet a person rather than a mere emblem.

Hair As Color Field

The blond hair in “Ancilla” is treated like a veil of light. Long, transparent strokes spill down in lemon and straw notes, animated by a few darker accents near the hat to mark roots and depth. The hair’s treatment is less descriptive than atmospheric; it increases the amount of warm, radiant color in the painting, turning the sitter into a lamp that warms the whole canvas. Those soft bands also mediate between the hard graphic of the hat and the soft wash of the background, bridging edge and field.

Brushwork And The Pleasure Of Speed

One of the painting’s charms lies in its visible speed. You can feel the brush slide thinly over the primed canvas, leaving the weave apparent in paler passages. The garment is indicated with broad, tawny scrubs; the hands and shoulders are specters made of pink smears; the turquoise bow is a fast, loaded stroke that breaks at its edges. This speed is not bravado; it is economy. By moving quickly, Matisse avoids overstatement and preserves a sense of air. The picture looks breathed rather than built, which suits a portrait about presence more than likeness.

Background As Quiet Architecture

The background is a pale, vertical rhythm—creamy stripes with the faintest shadowing. These barely-there bands stand in for wall panels or drapery and provide just enough structure to situate the sitter without pinning her to a specific place. Their verticality answers the hat’s lateral curves and the downward fall of the hair. Because they are close in value to the ground, they feel like light rather than wall, letting the figure float forward. The background’s restraint is crucial: too much information would drag the picture toward anecdote; too little would rob the head of a stage.

The Turquoise Corsage As Chromatic Pivot

The little knot of turquoise near the neckline is the painting’s hinge. It speaks with a different light—cool, aquatic, quick—than the rest. Its shape is more ragged, its paint more piled, so it catches the eye not only as a color but as a texture. The accent ties together several needs at once: it anchors the lower half of the portrait; it repeats, in reverse temperature, the hat’s gold spark; it prevents the warm ochres from becoming syrupy; and it adds an oblique suggestion of fashion and ornament appropriate to the Nice studio theater. Without that cool strike, the image would be softer but flatter; with it, the portrait gains snap.

Drawing With The Brush

Matisse’s line in this period is rarely a separate contour; it is the meeting of two colors or the edge of a loaded stroke. The hat’s silhouette is drawn by the collision of black and cream. The brows and eyes are placed with single gestures that bring calligraphic authority; the mouth is a compact, two-stroke decision. Even the suggestion of shoulders, hand, and garment hem are formed as edges of color rather than lines drawn on top. This approach fuses drawing and painting, so the portrait keeps unity in spite of its improvisatory look.

Light And The Illusion Of Modeling

There are no modeled shadows cast by hat or hair across the face, yet we accept light’s presence. Matisse creates the illusion by temperature shifts within areas—cooler touches at the eye sockets, warmer blushes at cheek and chin—and by value relations between large zones. The black hat makes the forehead luminous; the pale background makes the hair read as solid. The method is synthetic and modern: instead of imitating natural light, he constructs a convincing light through calibrated interactions.

Portrait Or Type?

The title “Ancilla” points to a role more than a specific individual; it means “handmaiden” in Latin and sounds, in several Romance languages, like a woman’s name. Matisse often oscillated between portrait and type. In the Nice years, models served as actors in a decorative theatre. He was less concerned with biographical likeness than with the degree to which a sitter could carry the orchestration of color and pattern he sought. In this sense “Ancilla” is a portrait of a mood—poised, slightly theatrical, warmly lit—more than of a single person’s identity.

Relation To Earlier Fauvism And Later Cut-Outs

Compared with the ferocity of 1905, this picture is restrained. Yet it relies on the same principles that made Fauvism radical: color used independently of description, contours that behave like graphic boundaries, and a belief that a few strong notes can carry an image. At the same time, the broad, simplified shapes and reliance on silhouette anticipate Matisse’s cut-paper decade to come. The hat could be a cut-out form; the hair reads like overlapping paper veils. “Ancilla” thus sits at a crossroads—oil behaving as if it already knew scissors.

The Psychology Of Reserve

Although the face is masklike, the portrait is not cold. The head’s soft tilt, the slight swell of the cheek against the lip’s decisive red, and the halo of blond strokes all generate a mood of quiet attention. The sitter is neither engaged nor aloof; she is held in a private temper, as if paused between movements in a small domestic theatre. That reserve is characteristic of Matisse’s Nice portraits. He wanted not confessional drama but a sustained chord of presence, something a viewer could live with rather than merely admire.

Material Candor And The Modern Portrait

Matisse leaves his methods in plain view: visible canvas, thin paint in some areas, richer pigment in accents, and edges that announce their making. This candor is part of the portrait’s modernity. Rather than build a polished surface that erases time and touch, he offers an object that shows its birth. The viewer recognizes the portrait not as an illusion captured once and for all but as a moment of seeing resolved into relationships that still breathe.

How The Parts Hold Together

Why does such a seemingly slight painting hold our attention? Because each part is tuned to a role in a compact structure. The hat establishes value contrast and graphic strength. The face offers a small theatre of red, black, and soft pinks. The hair expands warmth and introduces movement. The turquoise knot adds counter-temperature and texture. The background anchors the figure with gentle verticals while maintaining air. Nothing is redundant; each element earns its place.

Influence And Afterlife

Small portraits like “Ancilla” were admired by later painters and designers for their economy. Fashion photographers, poster artists, and illustrators learned from Matisse how a hat’s silhouette or a single accent color could do the work of pages of detail. Within Matisse’s own oeuvre, the portrait foreshadows the late paper cut-outs of faces and masks, where a handful of shapes and colors become fully human. It also keeps alive the connection to the theatrical—costume as pictorial architecture—that animates so many Nice interiors.

Conclusion

“Ancilla” proves that intimacy and authority can coexist. With a few strokes, a handful of hues, and the quiet confidence of a painter who knows what to leave out, Matisse builds a portrait that is both decorative and alive. The hat frames a face that hovers between mask and person; the blond hair turns into a field of light; a turquoise spark keeps the warmth alert; the background breathes. Nothing loud happens, and yet everything necessary occurs. The painting offers the pleasure of clarity—presence arranged by color.