Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

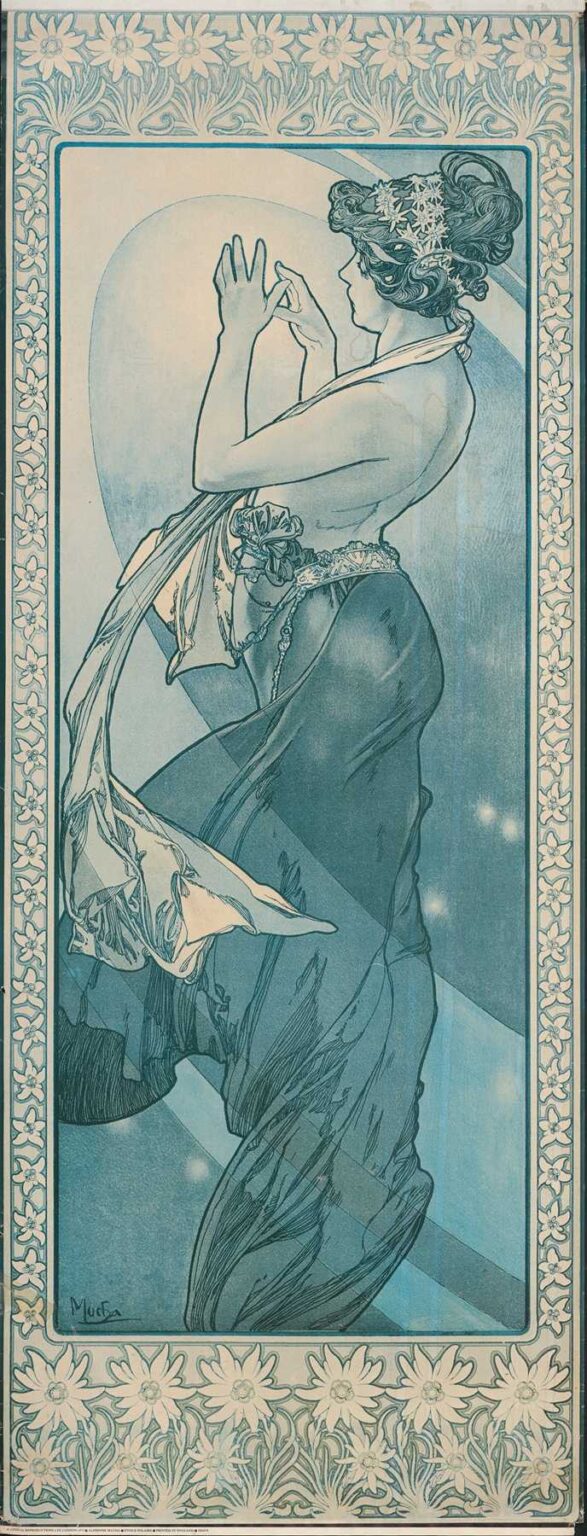

Alphonse Mucha’s “Female figure” is a tall, lyrical panel in which line, light, and ornament move with the ease of breath. A single woman in profile rises within a floral frame, her hands lifted as if shaping air. The color world is limited to cool, aqueous blues modulated from pale mist to deep teal, with accents of white that gleam along fabric folds and flowers. The result is both intimate and architectural: an allegorical presence held in a structure of borders, bands, and ovals that stabilize her dance. This is the Mucha idiom at full clarity—sensuous yet measured, decorative yet deeply attentive to the reality of a body turning through space.

Context and the Art Nouveau Ideal

By the last years of the nineteenth century, Paris had become a city of images. Posters did more than sell; they defined how the modern world should look. Mucha stood at the center of that transformation, creating a language of elongated formats, halo-like backdrops, and “whiplash” contours that turned passersby into spectators. While many of his sheets served opera stars and luxury goods, he also produced self-contained decorative panels that distilled mood without advertising text. “Female figure” belongs to that stream of autonomous images. It is a manifesto for the Art Nouveau belief that beauty arises when nature’s rhythms—growth, bloom, flow—are translated into line and pattern.

A Composition Built for Poise and Motion

The sheet is a column, proportioned like a door into a private theatre. Mucha sets a narrow inner frame with rounded corners just inside the floral border, then lets the woman expand to fill the interior. She is placed slightly right of center, moving left, which gives the composition a forward lean. A wide oval floats behind her like a plume of light, while diagonal bands cross the field, countering her turn with structural calm. The rhythm is simple and effective. Curves of hair, shoulder, hip, and scarf advance; geometry steadies them. The viewer senses both the freedom of movement and the order that contains it.

The Figure and the Psychology of Gesture

Mucha’s figures rarely shout; they shape. Here the woman raises both hands, thumbs touching, forefingers extended, the remaining fingers relaxed. The small triangle between the tips becomes a point of focus. She seems to study it, or perhaps to frame something at a distance. The gesture is deliberate but not stiff, a choreographed pause in which thought and movement coincide. It is tempting to read this as the creative act embodied: hands summon a form, mind attends, beauty precipitates. The calm profile contributes to that interpretation. Neither ecstatic nor melancholic, the face shows concentration softened by pleasure, the look of someone who knows that grace arrives through attention.

Drapery as the Language of Light

No one drew fabric like Mucha. In “Female figure” the long skirt and flowing sash are the visual score. Transparent layers slip over one another, catching the cool palette in different registers: smoky shadows at the knee, moonlit highlights along the hem, a breath of white at the trailing scarf that flares like a note at the end of a phrase. The contour never loses touch with gravity. Even the delicate ribbons have weight; they curve because they fall. This fidelity to physics allows stylization to feel true. The eye accepts the arabesque because it recognizes the tug of fabric and the shape of the body beneath.

Hair, Flowers, and the Crown of Spring

The coiffure is a small landscape of scrolls and waves, bound by a wreath of white blossoms. The flowers echo the border’s blooms and supply a crown without pomposity. Their whiteness is crucial in the restrained palette; they gather light around the face, where the viewer instinctively looks first. Mucha often used floral headpieces to fuse woman and season. Here the effect is less allegorical and more immediate: petals as cooled sparks lodging in hair, proof that the air itself is fresh.

The Border as Architecture and Garden

Acanthus-like stems and starry flowers run along the outer frame, at top and bottom in broad beds and at the sides in slender strips. This border does more than decorate; it builds. It acts like a carved portal through which the viewer peers. The organic forms are orderly, tap-rooted into a repeating rhythm that reinforces the panel’s vertical lift. Mucha’s genius lies in how that outer order makes inner freedom possible. The woman may sway and turn, scarves may fly, but the garden holds firm, the way a trellis allows a vine to flourish.

Geometry Behind the Dance

Two devices stabilize the moving figure: the big, soft oval and the muted diagonal beams in the background. The oval reads as a diffusion of light or a halo grown modern; the diagonals read as stage flats or beams of illumination. Together they create a shallow stage on which the woman’s silhouette reads crisply from a distance. They also provide an abstract rhythm within the color field, so that even the empty space carries meaning. In many posters Mucha used a circle to sanctify a performer’s status; here the geometry sanctifies an act of pure presence.

The Monochrome Palette and its Atmosphere

Limiting the sheet to blues and blue-greens, with white for brilliance, gives the image a unity very different from the warm abundance of Mucha’s champagne and theatre advertisements. The temperature is cool, which turns the slightest highlight into a gleam and keeps the whole from becoming sugary. The mood feels nocturne—moonlight more than sunlight—without narrative detail. This restraint opens the image to multiple readings: a memory, a reverie, a breath held before music begins. The palette also reveals the lithographic skill behind the print. With few stones to register, the printer could modulate tone subtly, letting thin veils of color pool and lighten like watercolor.

Line: The Calligraphy of the Body

Mucha’s contour has authority. It is neither a hard outline that cages form nor a timid thread that evaporates under pressure. It is calligraphy—thickening at the hip’s shadow, thinning at the wrist where light grazes the skin, quickening around folds where fabric doubles back. The face is built with a few decisive strokes; the hands, notoriously difficult to draw, are articulated with quiet confidence so that each knuckle reads, each nail gleams, and the little triangle of air between the fingertips vibrates with life. The entire panel could be stripped of color and it would still sing.

Reading Path and Visual Time

A well-designed panel controls how long the eye lingers. Here the journey begins at the bright flowers in the hair, slides to the profile, follows the line of the neck to the lifted hands, and then spirals down the sash, skirt, and trailing scarf before returning to the border blooms. The inner oval catches the gaze midway, keeping it from leaking off the sheet. This route turns viewing into a loop; by the time we reach the bottom border, we feel invited to travel back up along the opposite edge. The panel therefore supplies not only an image but a tempo—slow, circular, unhurried.

Costume, Ornament, and the Body Beneath

The belt of beads and the rosette at the hip articulate anatomy while avoiding vulgarity. The beads mark the turn of the waist and the pull of the abdomen beneath drapery; the rosette breaks the sweep of the sash into measured steps, like a metronome for the fabric. Mucha’s respect for the body is evident. He exalts its curves without denying bone and muscle. The result is sensual, not merely pretty, because it acknowledges how a living form supports the performance of cloth and gesture.

The Panel as Autonomous Object

Unlike Mucha’s famous posters, this composition carries no product name, star billing, or theatrical address. Its message is the pleasure of form itself. That autonomy matters historically. Art Nouveau sought to bring art into everyday life not only by beautifying advertisements but by offering panels that could hang in homes like tapestries. “Female figure” fits that domestic ambition. It would fill a narrow wall or door recess with tranquility, performing daily where grand canvases could not.

Echoes and Dialogues within Mucha’s Oeuvre

The panel converses with Mucha’s other series—his Arts, Seasons, and Precious Stones—without repeating a specific icon. The lifted hands recall the communicative choreography of his allegories of Music and Poetry; the cool palette nods to his zodiacal and calendar designs where blue connotes thought and evening. The floral border anticipates the frame-as-garden that often encircles his heroines. Seeing this panel among those cycles clarifies how Mucha built a vocabulary: floral crowns, elongated proportions, geometric haloes, and fabrics that behave like music.

Lithography and the Craft of Printing

Behind the elegance lies equipment, paper, and ink. Mucha designed for chromolithography, a process that lays color in layers from separate stones. The clear key drawing provided the spine; transparent blues and blue-greens supplied flesh, fabric, and backdrop; opaque white added sparks. The slight grain in the flats, visible as faint speckle, is a gift of the printing stone and the paper’s tooth. Rather than fight that texture, the artist uses it to suggest atmospheric depth. Register is precise, as seen in the clean separation of line and tone around the profile and fingers. It is a reminder that Art Nouveau’s grace is also a matter of craft discipline.

Nature Patterned, Not Imitated

The border flowers look like stylized edelweiss or starry daisies, but they are not botanical portraits. Mucha abstracts their structure—radial petals, tight centers, alternation of leaf and bloom—to create a repeat that never feels mechanical. That approach mirrors what he does with the figure. He does not mimic a snapshot; he distills a movement. In both frame and subject, nature is honored through pattern, which is how the eye remembers the world when it is at rest.

The Viewer’s Place

Standing before the panel, the viewer is gently elevated. The woman’s level is slightly above ours; her hands, poised to shape invisible air, suggest an art to which we bear witness. The border’s garden presents itself like a threshold. We are not asked to step through, only to linger and look. The image therefore operates like music heard from an adjacent room—clear enough to move us, distant enough to preserve its privacy. That balance of invitation and reserve is a Mucha hallmark.

Gender, Strength, and Grace

Mucha has often been praised and criticized for idealizing women. In this panel the idealization is respectful. The figure’s stance carries weight through the feet, hip, and shoulder; she is not a decorative doll but a body with momentum. Strength appears as poise rather than strain. The raised hands do not flutter; they think. In a culture that frequently used female figures as symbols without agency, this is not trivial. The woman here is the author of the panel’s central action: the making of form from air.

Why This Image Endures

More than a century on, “Female figure” feels contemporary because its essentials bypass fashion. The palette is modern in its restraint; the geometry could belong to a present-day brand system; the floral frame anticipates wallpaper and screen patterns still in use. But beyond those affinities lies a deeper reason: the image dramatizes the experience of creative attention. To watch the figure shape space with her hands is to be reminded of how ideas become visible—slowly, patiently, through care.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Female figure” is an object lesson in how an artist can choreograph seeing. A garden-like frame sets the stage; a cool palette calms the room; an oval of light and diagonal beams establish architectural order; a woman turns within that order, drapery spiraling as her hands compose a small triangle of air. Every element contributes to a single mood of poised invention. The panel neither advertises nor narrates. It simply presents a presence, proof that line and light, when attended with love and discipline, can sustain a world.