Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

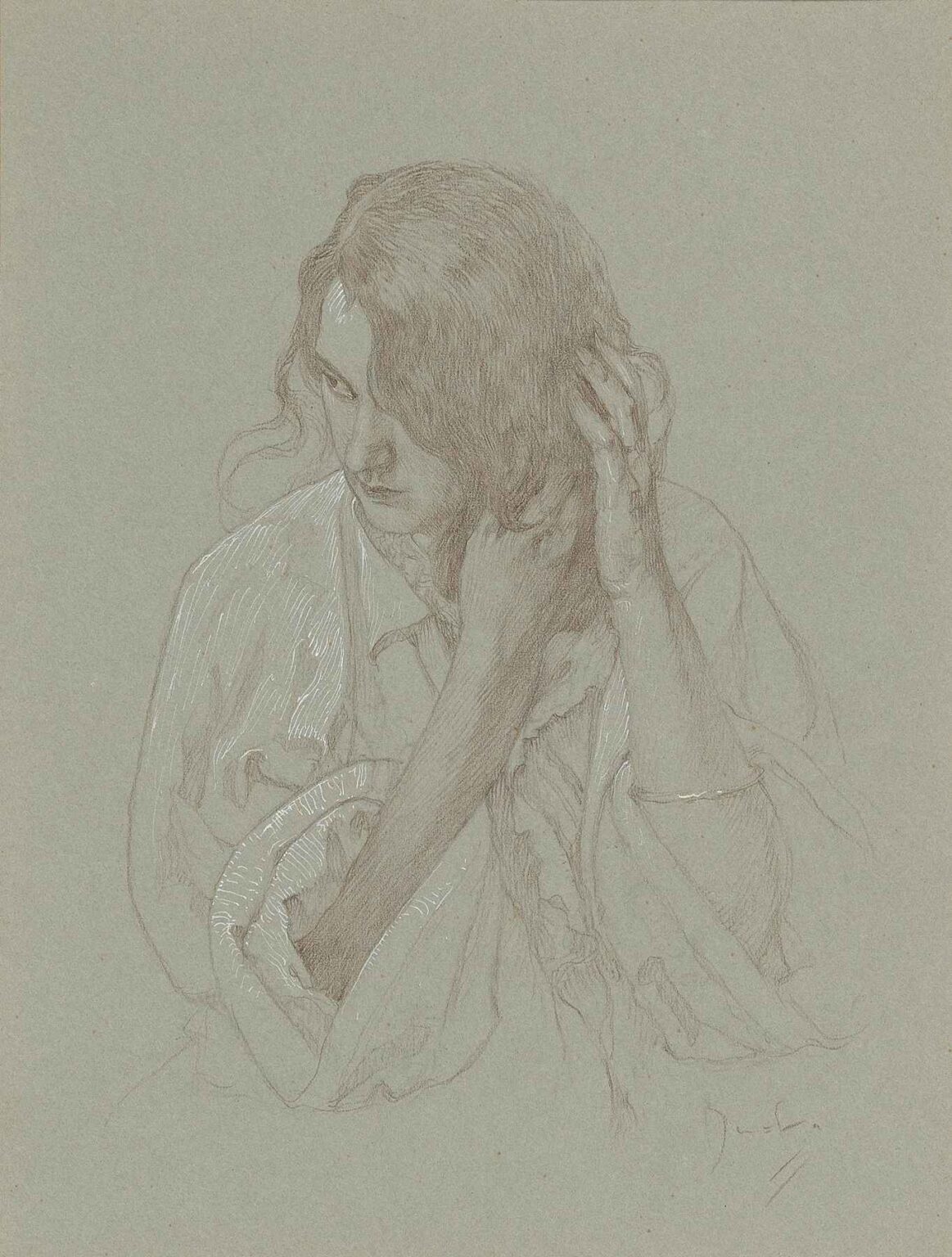

Alphonse Mucha’s “Portrait of a Girl with Hands in Hair” (c. 1898) stands as a testament to the artist’s extraordinary draughtsmanship, his nuanced understanding of feminine poise, and his mastery of tonal subtlety. Unlike the vibrant, fully realized lithographic posters that catapulted him to fame, this intimate drawing reveals Mucha’s skill in capturing a fleeting moment of personal introspection. Executed in graphite and white gouache on mid-tone gray paper, the work depicts a young woman in the simple yet profound act of arranging her hair—an unguarded gesture transformed into a study of grace, quiet concentration, and inner life. This analysis explores the drawing’s historical background, compositional strategies, technical execution, symbolic resonance, and its place within Mucha’s broader artistic trajectory, illuminating how a seemingly modest sketch can embody the highest ambitions of portrait art.

Historical Context

By the late 1890s, Paris had become the beating heart of the Art Nouveau movement, characterized by sinuous lines, organic motifs, and the fusion of fine art with applied design. Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), a Czech émigré, rose to prominence through his posters for the actress Sarah Bernhardt and various commercial clients, which defined the visual vocabulary of the era. Concurrently, he pursued more private endeavors—watercolors, gouaches, and drawings—showcased in Salon exhibitions and collected by connoisseurs. “Portrait of a Girl with Hands in Hair” emerges from this dual practice, reflecting a period when the advent of photography challenged traditional modes of representation. Mucha’s drawing reaffirmed the unique expressive power of manual draftsmanship, showcasing that the artist’s hand could convey psychological nuance, tactile presence, and decorative economy in ways the camera could not. In this vibrant cultural crucible—marked by Symbolist poetry, philosophical debates on individualism, and the rise of women as subjects rather than mere muses—Mucha’s portrait aligns with contemporary explorations of identity, introspection, and the inner life.

Commission and Purpose

While Mucha’s large-scale posters served commercial and promotional functions, his portrait drawings were often commissioned by private patrons or produced as personal studies. “Portrait of a Girl with Hands in Hair” may have been intended as a gift or a portfolio piece demonstrating his range beyond poster design. These intimate works allowed Mucha to refine his technique in a more leisurely context, free from the deadlines and technical constraints of chromolithography. Whether based on a professional model, a friend, or a family member, the drawing exemplifies Mucha’s belief that the act of drawing was itself a creative discipline—one that demanded acute observation, emotional empathy, and rigorous attention to formal detail. The very informality of the sitter’s gesture suggests that the drawing was executed from life, capturing a spontaneous moment rather than a contrived pose.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Mucha organizes the composition around a central vertical axis defined by the sitter’s posture and downward gaze. The drawing’s rectangular format is enlivened by a subtle triangular structure: the apex formed at the intersection of her elevated right hand and cascading hair, balanced by her left hand grounded at the base of her neck. This gently sloping triangle creates visual tension and guides the viewer’s eye from the top of the head, down the arms, to the folds of the garment. Mucha deliberately omits a detailed background, allowing the gray paper to recede and focus attention squarely on the figure’s form. Negative space surrounds the sitter, imbuing the drawing with an atmosphere of quietude and introspection. Unlike more formal portraiture, where context or props frame the subject, here the simplicity of the setting underscores the universality of the moment—an archetype of self-care and feminine elegance.

Line Quality and Gestural Rhythm

At the core of the drawing’s vitality is Mucha’s masterful modulation of line. He begins with delicate, fluid pencil strokes to map the contours of the face, hands, and shoulders, employing consistent, confident lines that convey both firmness of form and softness of flesh. As the drawing progresses, certain passages—such as the heavy locks of hair and the deep folds of drapery—receive bolder, more layered graphite, emphasizing shadow and volume. In contrast, the white gouache highlights on the hair’s crest, cheekbones, and the garment’s flowing edges create a chiaroscuro effect without resorting to heavy black masses. These highlights, applied with a fine brush, trace the light as it skims across surfaces, lending the figure a three-dimensional presence. Mucha’s lines exhibit a natural rhythm—the sinuous curves in the arms echo those in the hair, while the vertical strokes in the sleeves counterbalance the horizontal sweep of shoulders. This interplay of curve and countercurve produces a visual dance, reflecting both the fluidity of hair and the fluidity of line itself.

Tonal Modulation and the Role of Mid-Tone Paper

Choosing mid-tone gray paper for the portrait served both practical and aesthetic purposes. The paper’s neutral tone provided an immediate middle value, allowing Mucha to work both darker (with graphite) and lighter (with gouache) to achieve a full range of tones. He exploited this by reserving deeper graphite for areas of shadow—the underside of the chin, the recess between the arms, the folds in the garment—while using white gouache to lift highlights on the forehead, collarbone, and the hair’s lustrous strands. The gradual transition between dark and light is smooth, with minimal abrupt shifts, reflecting a sculptural sensibility. Mucha’s tonal gradation suggests subtle planes of form: the roundness of cheeks, the hollow of the neck, the slope of shoulders. The paper’s slight tooth gives texture to the drawing, preventing overly slick surfaces and reinforcing the materiality of the medium. Together, the combination of mid-tone support, graphite, and white pigment yields a harmonious tonal architecture that feels both natural and idealized.

Depiction of Fabric and Texture

A hallmark of Mucha’s draftsmanship is his ability to render a wide variety of textures through minimal means. In this portrait, the sitter’s garment—perhaps a loose blouse or wrapper—features billowing sleeves and softly gathered folds. Mucha implies these textures through a few strategic washes of graphite and measured cross-hatching, suggesting the way the fabric drapes across the body. The interplay of thicker graphite lines for deeper folds and lighter strokes for gentle undulations communicates the tactile quality of cloth. By contrast, the skin areas remain largely unmarked, save for the essential contour lines and white highlights, allowing the smoothness of flesh to emerge through the paper itself. Hair, perhaps the most challenging texture, is handled with a combination of fine, directional strokes and subtle smudging to capture both individual strands and overall volume. The drawing thus becomes a study not only of anatomy and gesture but also of material contrasts—between skin, fabric, and hair.

Psychological Presence and Emotional Ambiguity

While the act of arranging one’s hair might seem mundane, Mucha imbues the gesture with psychological depth. The sitter’s slightly furrowed brow and downcast gaze suggest concentration—perhaps self-consciousness, introspection, or even a fleeting moment of melancholy. The sideways glance, with eyes not meeting the viewer, cultivates an aura of private reverie. Her parted lips and the tension in her fingertips hint at an imminent thought or feeling, capturing a transient emotional cusp. Mucha does not impose a narrative; instead, he provides clues—posture, expression, gesture—that invite viewers to project their own interpretations. Is the subject preparing for a social event? Engaged in a moment of self-reflection? Experiencing vulnerability? This open-ended psychological ambiguity elevates the drawing from a mere physical likeness to a poignant exploration of inner life.

Relationship to Mucha’s Decorative and Theatrical Work

Although “Portrait of a Girl with Hands in Hair” differs dramatically in scale and purpose from Mucha’s decorative posters and theatrical lithographs, it shares underlying formal principles. The emphasis on flowing line, harmonious curves, and balanced composition echoes his poster designs for Sarah Bernhardt and commercial clients. However, here the decorative impulse is sublimated in service of character study rather than promotional spectacle. The figure’s posture—graceful, elongated, and framed within an imaginary compositional grid—anticipates the elegant silhouettes of Mucha’s allegorical panels (“Painting,” “Poetry,” “Music”). Simultaneously, the drawing’s focus on a single, isolated figure prefigures Mucha’s theatrical portraiture, where he captured actors in costume with a similar blend of immediacy and idealization. This portrait thus bridges the realms of commercial design, allegorical personification, and intimate gesture drawing.

Influence on Contemporary Draftsmanship and Figurative Art

Mucha’s practice of integrating graphic sensibility with fine-art draftsmanship inspired a generation of illustrators and portrait artists in the early 20th century. His method of combining mid-tone paper with graphite and white gouache became a staple in academic ateliers, prized for teaching students how to achieve full tonal ranges without heavy reliance on black. The psychological subtlety he achieved through minimal gestures—gestural hair arrangement, lowered gaze—offered a model for capturing character with economy. In contemporary art education, Mucha’s drawings are studied alongside Old Master preparatory sketches, demonstrating their technical rigor and expressive power. Graphic novelists and concept artists continue to draw upon Mucha’s synthesis of line rhythm and tonal modulation, adapting his techniques for digital mediums. The lasting legacy of “Portrait of a Girl with Hands in Hair” lies in its demonstration that draftsmanship can be both technically exacting and emotionally eloquent.

Conservation, Provenance, and Exhibition History

Many of Mucha’s original drawings, including intimate portraits like this, passed into private European collections or the holdings of the Mucha Foundation. Conservation of works on paper demands careful control of humidity, light exposure, and acid-free mounting. Recent exhibitions of Mucha’s drawings—such as the 2018 retrospective in Prague—have helped reintroduce these lesser-known pieces to broader audiences. Museum catalogues and scholarly publications have traced the portrait’s provenance, underscoring its importance in understanding Mucha’s oeuvre beyond his iconic posters. When displayed alongside his graphic and painted works, the drawing offers viewers a fuller picture of Mucha’s range, illuminating the continuity between his decorative and deeply personal art.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Portrait of a Girl with Hands in Hair” exemplifies the artist’s dual mastery of decorative line and human psychology. Through a harmonious interplay of fine graphite strokes, white gouache highlights, and the subtle embrace of mid-tone paper, Mucha captures a fleeting moment of introspection and poised grace. The portrait stands at the confluence of several artistic currents—Art Nouveau ornament, Salon draftsmanship, Symbolist emphasis on inner life—while pointing forward to modern explorations of gesture and character. Its influence resonates in the continued value placed on hand-drawn portraiture, teaching generations of artists to see the extraordinary in simple human acts. More than a technical showcase, the drawing invites viewers into a private reverie, reminding us that art’s deepest power lies in its ability to render the invisible contours of thought and feeling.