Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

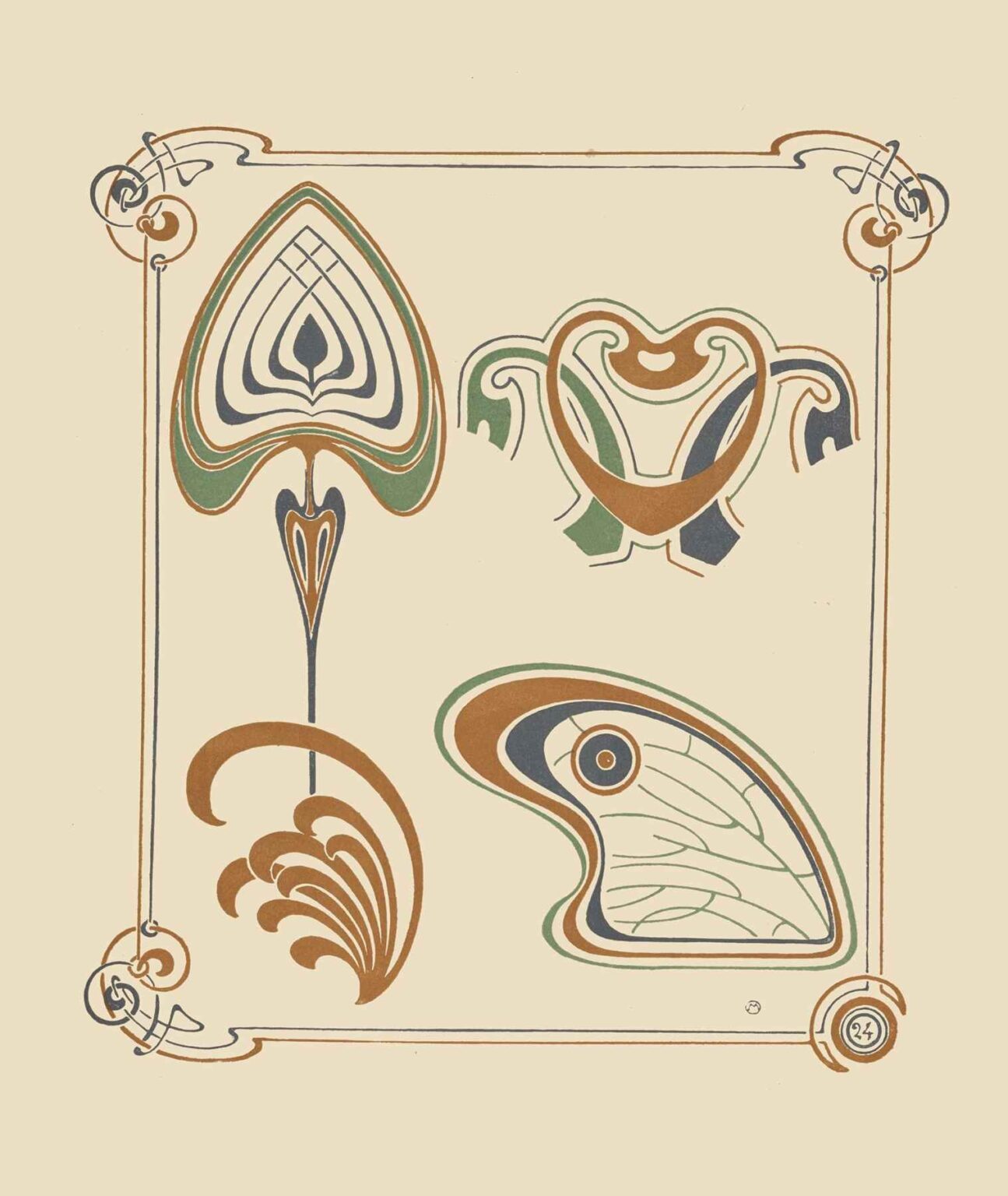

At the turn of the 20th century, Alphonse Mucha expanded his celebrated poster art into a realm of pure ornamental abstraction. His 1900 work, “Abstract design based on wings and leaf shapes,” exemplifies this exploration, distilling natural motifs into a harmonious interplay of form, line, and color. Rather than depicting a narrative or human subject, Mucha elevates the decorative principle itself, treating wings and foliage as graphic elements that dance across the surface. The composition, rendered in a limited yet rich palette, unfolds within a slender border punctuated by signature corner knots. Each motif—whether a stylized wing or a curling leaf form—functions both as an independent study and as part of a cohesive visual whole. By examining this work through historical, formal, chromatic, symbolic, and technical lenses, we can appreciate how Mucha transformed botanical and avian references into an autonomous language of ornament, bridging the gap between fine art and applied design.

Historical Context

Created at the height of the Art Nouveau movement, “Abstract design based on wings and leaf shapes” reflects the era’s rejection of academic historicism in favor of organic inspiration. Mucha, born in 1860 in Moravia, had gained international acclaim in Paris with his posters for Sarah Bernhardt and commercial clients during the 1890s. Simultaneously, Europe experienced a flourishing interest in decorative traditions from diverse cultures—Islamic arabesques, Japanese woodblock prints, medieval illuminated manuscripts—all sources that fueled the Art Nouveau ethos. In Mucha’s workshop, ornamental studies served as prototypes for wallpapers, textiles, and book illustrations, underscoring the movement’s goal to integrate art into everyday life. This particular design belongs to a series of abstract panels he produced around 1900, each exploring different facets of nature’s forms. By combining wings—symbols of flight, aspiration, and transformation—with leaf shapes—emblems of growth, renewal, and organic vitality—Mucha synthesized motifs that resonated with contemporary tastes and spiritual yearnings.

Formal Structure and Composition

The painting is enclosed by a narrow rectangular border composed of two parallel lines that flow into intricate corner knots, framing the central motifs without confining them too tightly. Within this boundary, four primary studies occupy the quadrants: two wing-inspired forms at top left and top right, and two leaf-derived shapes at bottom left and bottom right. The upper left motif resembles a stylized bird’s wing, composed of interlocking curved segments that fan outward from a central axis. Opposite, the upper right design echoes this structure but inverts the curvature and alters the arrangement of segments, creating a visual counterpoint. Below, the bottom left motif mimics a cluster of elongated leaves radiating from a slender stem, its sinuous lines curling into a scroll. The bottom right motif presents a single leaf abstracted into concentric arcs and feather-like veins, combining the wing’s rhythmic layering with the leaf’s internal structure. Negative space—unpainted background—plays a crucial role, allowing each form to breathe and reinforcing the flatness of the surface. The asymmetry of the four motifs is balanced by their shared geometric language: curves, rhythmic repetition, and mirrored echoes that guide the viewer’s eye in a circular journey around the composition.

Color and Line Dynamics

Mucha’s palette in this work is notably restrained, deploying only three principal colors—deep olive green, warm ochre, and muted slate blue—against a neutral beige ground. Each hue corresponds to specific motifs: the olive green predominates in one wing form and the leaf cluster, suggesting verdant vitality; the ochre emphasizes the opposing wing and the veined leaf, imbuing them with warmth; the slate blue appears in minor accents, reinforcing structural lines and adding depth. The careful balance of warm and cool tones creates a visual tension that energizes rather than overwhelms. Line is the work’s driving force: Mucha employs varied line weights, using thicker strokes to define main outlines and finer, pen-like lines for interior detailing such as vein patterns and segment separations. The junctions where bold and delicate lines meet generate a sense of relief, as if the motifs hover slightly above the surface. Furthermore, slight irregularities—incomplete outlines or gentle waviness—lend a human touch, reminding viewers of the handcrafted process behind the apparent precision.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Although abstracted, the motifs in “Abstract design based on wings and leaf shapes” carry symbolic resonances that deepen the painting’s impact. Wings are universal emblems of freedom, transcendence, and spiritual aspiration; their stylized depiction here suggests both the structural elegance of a bird’s wing and the ethereal sweep of an angel’s feather. Leaves, by contrast, recall earthly growth, regeneration, and the cyclical rhythms of nature. By placing these two symbolic families in dialogue, Mucha invites viewers to contemplate the interplay between material and spiritual realms. The repeating segments within each motif evoke ideas of unity through multiplicity—individual feathers forming a wing, individual veins nurturing a leaf—underscoring that strength and beauty emerge from collective harmony. The flat background and absence of contextual clues free the symbols from literal narrative, allowing each viewer to project personal associations, be they flights of imagination or meditative reflections on growth and renewal.

Technical Execution and Medium

Executed likely in gouache or tempera on a rigid paper or board support, the painting reveals Mucha’s mastery of both graphic and painterly techniques. The smooth surface facilitated the crisp application of opaque pigments, while the medium’s matte quality avoided glare and foregrounded form. Mucha’s process probably began with light pencil or ink underdrawings to position the four motifs and establish proportional relationships. For the curved segments and concentric arcs, he may have used compass or French curve tools, whereas the more organic leaf shapes and vein details were drawn freehand with a fine brush or pen. The uniformity of the border lines and corner knots indicates careful measurement and planning, yet the occasional pooling of pigment at stroke ends betrays a living hand behind the precision. The interplay of wet-into-wet brushwork for smooth color transitions and dry brush or pen work for crisp contours exemplifies Mucha’s fluid command of diverse techniques.

Relation to Art Nouveau Philosophy

“Abstract design based on wings and leaf shapes” embodies Art Nouveau’s core principle: the synthesis of art and life through organic forms. Rejecting rigid historicist styles, artists and designers of the movement drew inspiration directly from flora, fauna, and natural patterns, integrating them into architecture, furniture, jewelry, and graphic arts. Mucha’s ornamental panels served as reference models for applied projects, demonstrating how decorative motifs could be both aesthetically compelling and functionally adaptable. The painting’s seamless curves and rhythmic repetitions echo the flowing ironwork of Hector Guimard’s Paris Métro entrances and the luminous glass artworks of Émile Gallé. Yet Mucha’s unique contribution lies in his ability to distill these inspirations into a purely graphic language, one that celebrates the line as a living entity and ornament as an autonomous art form. In doing so, he helped blur the boundaries between fine art and design, a legacy that resonates strongly in 20th-century modernism.

Position within Mucha’s Oeuvre

While Mucha’s figurative posters—such as “The Seasons,” “Gismonda,” and “The Slav Epic”—remain his best-known works, his decorative studies represent a parallel vein of innovation. Between 1897 and 1902, he published several albums of ornamental designs, exploring arabesques, floral patterns, and abstract motifs. “Abstract design based on wings and leaf shapes” occupies a distinctive place in this corpus, uniting avian and botanical references in a graphic synthesis. Unlike designs intended solely for repeat patterns, this panel functions equally as an autonomous artwork and as a potential template for applied projects. The painting’s combination of structured geometry and fluid spontaneity reflects Mucha’s dual identity as both graphic designer and fine artist. By experimenting with abstraction at this early stage, he prefigured aspects of later 20th-century movements—Art Deco’s stylized motifs, Bauhaus pattern books, and even mid-century modern textile designs.

Influence and Legacy

Although overshadowed by his poster fame, Mucha’s ornamental abstractions have exerted a lasting influence on decorative arts and graphic design. Pattern books featuring his designs circulated widely among craftspeople, textile manufacturers, and print publishers, who adapted his motifs for wallpaper, fabric, ceramics, and metalwork. The revival of Art Nouveau in the 1960s and ’70s prompted renewed interest in his lesser-known works, leading to exhibitions and reprints of his design portfolios. Today, digital designers draw upon Mucha’s principles—curve modulation, line weight variation, and balanced asymmetry—when creating vector-based patterns and interfaces. Art historians recognize these ornamental studies as parallel origins of abstraction in Western art, challenging nostalgia narratives that confine modernism’s birth to avant-garde painters. The interplay of structural clarity and organic fluidity in this painting continues to inspire artists and designers who seek to merge precision with expressive freedom.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Abstract design based on wings and leaf shapes” stands as a testament to the transformative power of ornament. Through the alchemy of line, color, and symbolic suggestion, he elevates natural motifs into a self-contained visual language that transcends function. The painting embodies Art Nouveau’s rejection of academic art, its embrace of organic inspiration, and its ambition to fuse art with everyday life. At the same time, it anticipates modern design’s quest for abstraction, modularity, and integrated form. Revisiting this work today offers a rich source of insight for artists, designers, and admirers alike, reminding us that the simplest curves and silhouettes can convey profound ideas about freedom, growth, and unity.