Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

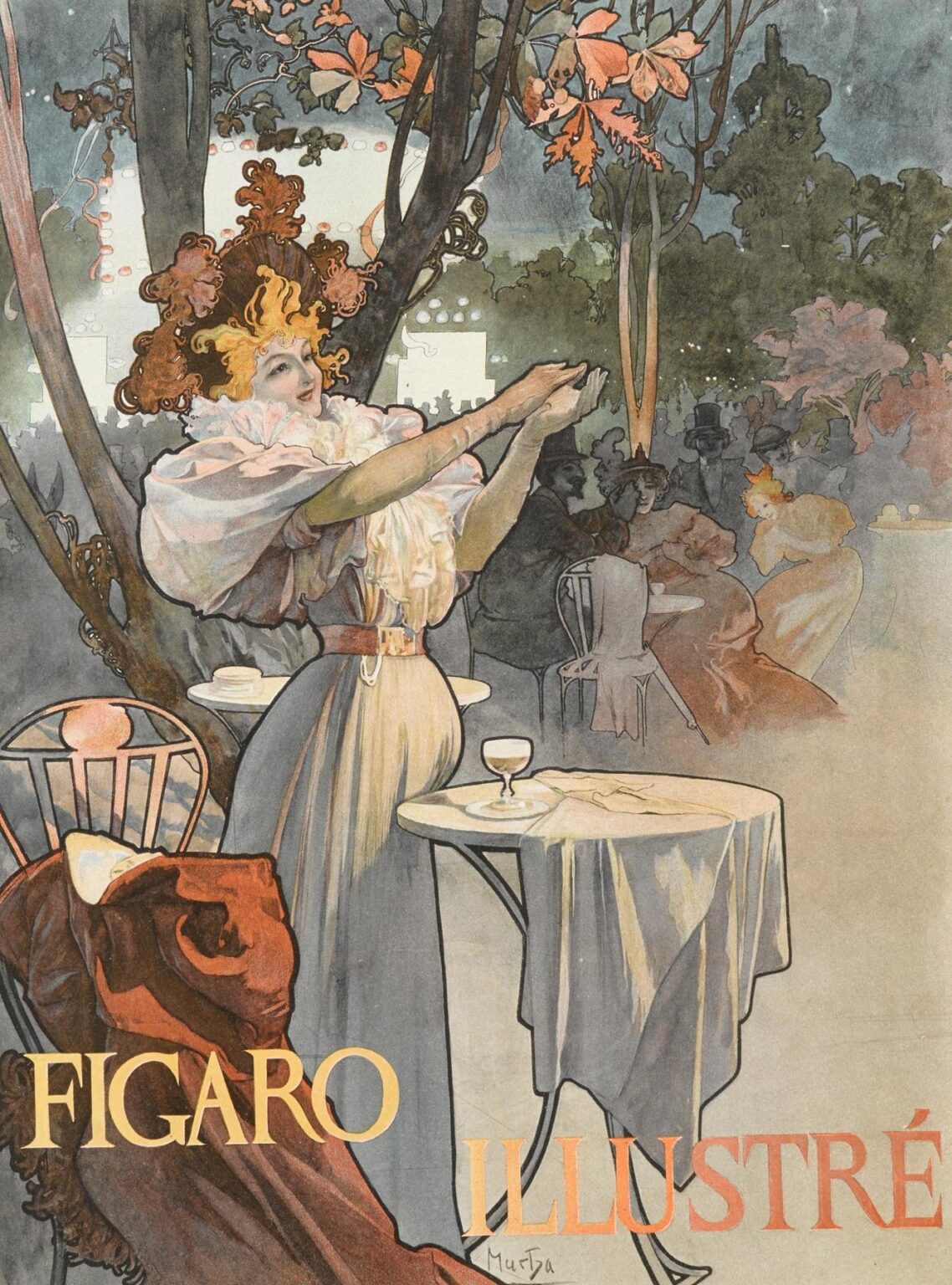

Alphonse Mucha’s “Figaro” (1898) stands among the most celebrated magazine covers of the Belle Époque. Commissioned for Le Figaro Illustré, the poster merges the exuberance of Parisian café life with the refined decorative language of Art Nouveau. At its center is a striking female figure, caught in mid‐toast, her blouse of gossamer ruffles and her coiffure of golden curls illuminated by ambient light. Around her, an animated crowd lounges at wrought‐iron tables beneath swaying trees and glowing globes. Though crafted as a commercial illustration, “Figaro” transcends its magazine‐cover function to become a timeless study in mood, movement, and ornamental harmony. Throughout this analysis, we explore its historical context, compositional mastery, color and technique, symbolic resonance, and lasting influence on graphic design.

Historical and Cultural Context

By the late 1890s, Paris was the epicenter of artistic innovation and social dynamism. The capital’s cafés and terraces teemed with writers, artists, politicians, and the emerging middle class. Le Figaro Illustré, launched in 1897 as an offshoot of the daily newspaper, sought to capture this spirit through richly illustrated issues covering literature, fashion, and society. Mucha, fresh from his success with theatrical posters, was tapped to create the cover for the magazine’s special summer number. His appointment reflected publishers’ growing recognition that visually striking artwork could drive circulation and embody editorial identity. In “Figaro,” Mucha distilled the joie de vivre of Parisian cafés into a single, unforgettable image, aligning his decorative vision with the magazine’s cosmopolitan ethos.

Purpose and Editorial Function

Beyond its surface beauty, the “Figaro” cover functioned as a visual thesis for Le Figaro Illustré’s brand. The image invited readers to partake in the convivial atmosphere that awaited within its pages—reviews of new plays, gossip on fashionable promenades, and glimpses of elegant society. By featuring a glamorous protagonist raising her glass, Mucha signaled that the issue would offer both wit and refinement. The scene’s dusk‐lit tones and atmospheric haze suggested after‐hours indulgence, promising exclusive access to Paris’s cultural nocturne. Thus, the cover performed dual roles: it was an enticement for potential buyers on the newsstand and a thematic overture for subscribers eager to immerse themselves in Belle Époque splendor.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Mucha structures the “Figaro” composition around a central vertical axis anchored by the woman’s poised form and the nearest café table. Her uplifted arm and the wineglass she holds create a diagonal counterpoint that guides the eye across the scene. Behind her, the tree trunk and branches rise, framing the middle ground where clusters of patrons gather in animated conversation. The background dissolves into a tapestry of points of light—gas lamps and strings of bulbs—suggesting the broader cityscape. Mucha balances densely detailed areas (the woman’s blouse, tree bark, café chairs) with more loosely rendered sections (distant figures and foliage), crafting a sense of depth without recourse to strict perspectival accuracy. The interplay of foreground clarity and background suggestion mirrors the way human perception hovers between focus and ambiance in real life.

Mastery of Line and Ornament

At the heart of Mucha’s aesthetic lies his command of sinuous line. In “Figaro,” the ruffles of the woman’s blouse unfurl in graceful arcs, each fold defined by variable line weight that imparts volume without heavy shading. Her hair, a cascade of undulating curls, seems almost alive, echoing the nearby branches. The wrought‐iron chairs and balcony railings exhibit ornamental curves that harmonize with organic forms. Even the contour of a distant figure or a tabletop edge exhibits a calligraphic flourish. Mucha’s lines both delineate figures and morph into decorative motifs, reinforcing Art Nouveau’s principle that ornament and form should emerge from a single, unified gesture.

Color Palette and Watercolor Technique

Unlike his bold, high‐contrast lithographic posters, Mucha employed a subtler watercolor technique for the “Figaro” cover. Muted grays and smoky blues define the evening sky and distant foliage, while warmer pinks, creams, and ochres illuminate the foreground. The woman’s blouse glows with pearlescent highlights, the folds picking up a delicate iridescence. Reds and russets in her hair and the table cloths underline the festive atmosphere. Mucha applied pigments in transparent washes, layering delicate glazes to achieve depth and soft transitions. This painterly approach complements the illustration’s loose handling of detail in the background, enhancing the atmosphere of twilight. The overall palette evokes the sensation of dusk—the moment when daylight’s clarity yields to the soft luminescence of artificial lights.

Symbolism and Narrative Allusion

While on one level “Figaro” simply depicts a café scene, Mucha imbues it with symbolic resonance. The central figure’s lifted glass functions as an emblem of toast and celebration, suggesting camaraderie and shared experience. Her direct gaze invites complicity: she looks out at the viewer as if to include them in the evening’s revelry. The glowing lights overhead nod to modernity and urban progress, while the natural forms of tree branches remind viewers that even in the city, human culture remains rooted in organic rhythms. In the context of a literary magazine, the scene becomes a metaphor for intellectual exchange: ideas passing among animated groups as freely as wine glasses are passed from hand to hand.

Representation of Feminine Sophistication

Mucha’s female protagonists often embodied an ideal of cultivated femininity—both elegant and assertive. In “Figaro,” the woman’s confident posture and direct engagement with the viewer mark her as the locus of the composition and the issue’s thematic focal point. Her off‐the‐shoulder blouse and cinched waist celebrate the latest in Parisian fashion without resorting to excessive eroticism. Her expression—playful yet poised—suggests wit, charm, and a cosmopolitan sensibility. Mucha’s portrayal reflects contemporary aspirations: women of the Belle Époque sought both social freedom and cultural refinement, and the “Figaro” cover offers an image of feminine modernity that resonates with both female and male readers.

Depiction of Urban Entertainment

The café‐terrace setting, with its proliferation of chairs, tables, and well‐dressed figures, captures a quintessential feature of Parisian life at the turn of the century. Cafés served as hubs of artistic and intellectual activity, where writers drafted works by gaslight and actors dined in gauzy gowns between rehearsals. Mucha’s scene, though idealized, conveys the social density and relaxed elegance of such gatherings. Figures in the middle ground appear in mid‐conversation, their gestures and hats outlined with economy—just enough detail to convey individuality without distracting from the lady in front. The interplay of seated groups, standing figures, and receding silhouettes evokes the dynamic ebb and flow of public life.

Integration of Text and Image

Typography in the “Figaro” cover adheres to Mucha’s principle that words and image should form a cohesive whole. The magazine title “FIGARO ILLUSTRÉ” appears in a bold, slightly condensed serif typeface that balances weight and elegance. Its warm apricot tones echo the luminous highlights in the woman’s hair and the reflected glow of lamps. Placed across the lower section, the lettering unifies foreground and mid-ground, while avoiding direct overlap with critical visual elements. Mucha’s approach ensures that the title is legible at a distance—crucial for newsstand display—without disrupting the illustration’s atmospheric integrity.

Influence of Japonisme and Eclectic Ornament

Mucha drew inspiration from Japanese woodblock prints, particularly in his use of flattened color areas and decorative borders. Though the “Figaro” cover lacks a strict rectangular frame, the trellis‐like lines of café chairs and the repeated forms of tablecloths and foliage reveal Japonisme’s emphasis on pattern and surface. At the same time, Mucha’s eclectic blending of classical drapery, medieval‐inspired ruffs, and contemporary couture exemplifies the era’s tendency to mix historical references into a fresh modern style. This synthesis creates a decorative vocabulary uniquely suited to Paris’s cosmopolitan tastes.

Technical Collaboration and Print Production

Though Mucha’s watercolors served as the model, the final magazine cover was reproduced via photomechanical processes available in the late 19th century. Mucha’s originals informed the engraving plates and color separations, requiring skilled technicians to translate brushwork and delicate washes into printable dots or stipples. The reproduction needed to preserve the soft tonal transitions and the crisp lines of his drawing, demanding meticulous calibration of inks, plates, and press runs. The success of this process contributed to the cover’s impact, ensuring that the magazine hit newsstands with a visual fidelity that conveyed both Mucha’s artistry and the publication’s premium quality.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its appearance, the “Figaro” cover drew immediate attention from readers and fellow artists. Collectors prized early issues for their sumptuous imagery, and competing magazines sought to emulate Mucha’s blend of elegance and modernity. In subsequent decades, Mucha’s café scenes—including “Figaro” and his images for La Plume—became icons of turn‐of‐the‐century graphic design. The opening of Musée Mucha in Prague and major Museum exhibitions across Europe rekindled interest in these works, influencing 20th‐century pioneers from Art Deco designers to mid‐century illustrators. Today, “Figaro” cover reproductions adorn cafés, galleries, and boutique hotels, continuing to evoke the allure of Belle Époque conviviality.

Preservation and Modern Resonance

Original Le Figaro Illustré issues with Mucha covers are delicate artifacts, susceptible to paper acidity and light damage. Archival framing, deacidification treatments, and controlled display conditions help preserve their luminosity for future generations. Digital archives have made high‐resolution scans available to scholars and enthusiasts, facilitating detailed study of Mucha’s technique and compositional choices. Contemporary graphic designers and illustrators often cite the “Figaro” cover as a touchstone, drawing on its principles of integrated typography, harmonious palette, and narrative ambiance. Its enduring appeal underscores the notion that great design—grounded in narrative and technical mastery—remains perennially relevant.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s “Figaro” cover exemplifies the union of artistry and editorial purpose that defines Art Nouveau’s greatest achievements. Through sinuous line, atmospheric color, and engaging allegory, Mucha captured the spirit of Parisian café culture and translated it into an image of unforgettable elegance. The cover’s narrative of toast and conviviality resonates with readers across time, symbolizing the universal allure of shared laughter under glowing lights. More than a magazine illustration, “Figaro” stands as a testament to the power of design to shape cultural identity—an invitation to partake in beauty, conversation, and the sensual pleasures of modern life.