Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

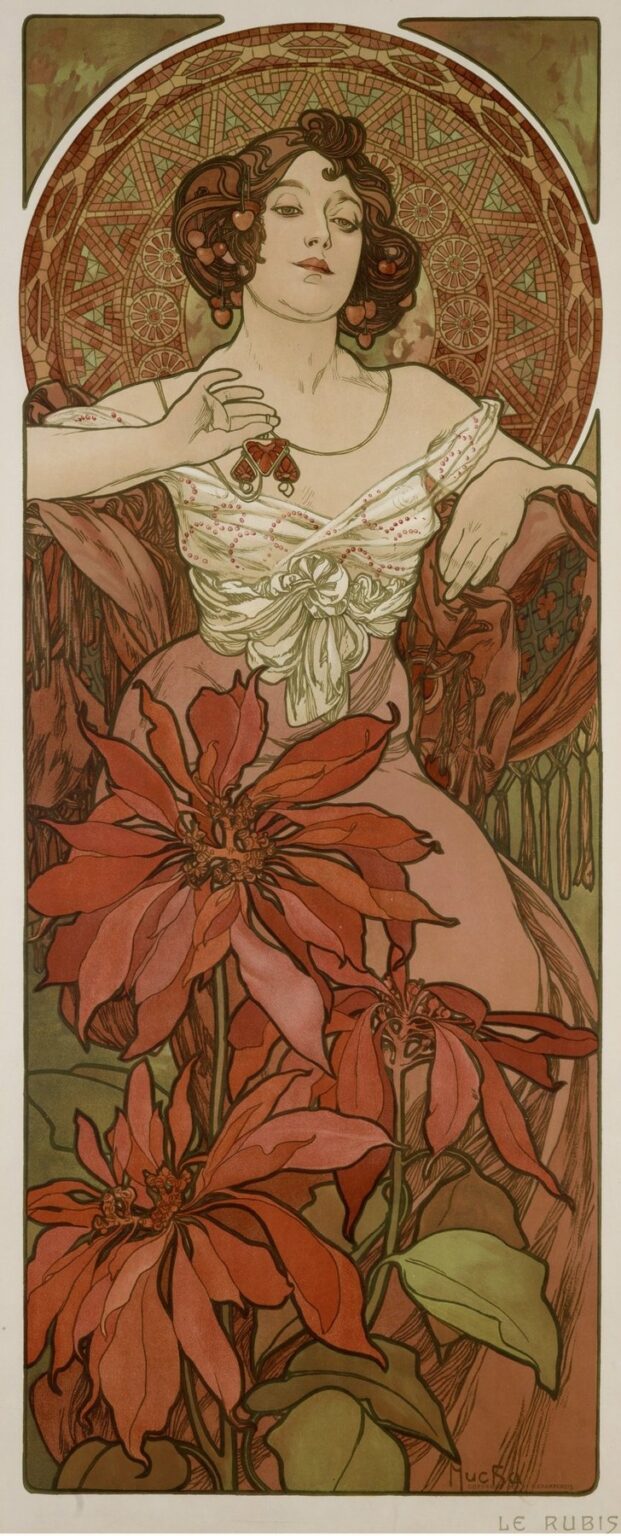

Alphonse Mucha’s The Ruby (Le Rubis), executed in 1900, stands as one of the most iconic manifestations of the Art Nouveau movement. Originally conceived as a decorative panel to illustrate a series celebrating precious gemstones, this work transcends its role as mere ornament to become a profound exploration of beauty, symbolism, and decorative harmony. At its center, a languid female figure embodies the qualities of the ruby—passion, vitality, and regality—while her surrounding environment and ornaments echo the gemstone’s fiery allure. Mucha’s seamless fusion of figure, ornament, and symbolic resonance demonstrates his mastery of line, color, and composition, and illustrates his belief that art should permeate every facet of modern life.

Historical and Cultural Context

The dawn of the twentieth century saw Paris at the epicenter of artistic innovation. The rigid academic traditions of the late nineteenth century were giving way to new currents inspired by Japanese prints, medieval craftwork, and the organic forms of nature. This cultural ferment gave rise to the Art Nouveau movement, which flourished between 1890 and 1910. Artists, architects, and designers sought to dissolve the boundaries between fine art and decorative art, forging a total art experience—Gesamtkunstwerk—that united painting, sculpture, jewelry, interiors, and graphic design. Alphonse Mucha, a Czech émigré who arrived in Paris in 1887, quickly became the poster boy of Art Nouveau through his celebrated designs for theater impresario Sarah Bernhardt. By 1900, Mucha was experimenting with other formats, including decorative panels celebrating gemstones, seasons, and allegorical themes. The Ruby emerges against this backdrop, embodying the era’s aspiration to elevate everyday objects—and even advertising—to the level of high art.

Commission and Series

Much of Mucha’s work on gemstone panels was undertaken for gift books, decorative portfolios, and exhibitions. The Ruby formed part of a series in which each painting personified a different precious stone—emerald, amethyst, topaz, and so forth—through allegorical figures set amidst complementary botanical and ornamental motifs. While details of the original commission remain somewhat obscure, surviving preparatory sketches and print editions suggest that Mucha intended these panels for display in private salons or as illustrations in limited-edition art books. The series allowed him to explore the unique symbolic and chromatic properties of each stone, applying his graphic sensibility to the realm of decorative painting. The Ruby therefore belongs to a larger constellation of works in which Mucha translated the intrinsic character of gemstones into human form and decorative composition.

Composition and Form

The Ruby is organized as a tall, vertical panel that seamlessly blends figure and ornament. The lower two-thirds of the composition is dominated by a cluster of large, stylized flowers—possibly poinsettias or clematis—rendered in ruby-red tones. Their sweeping petals and broad leaves anchor the viewer’s gaze and convey a sense of lush abundance. Above this floral foreground sits the central figure, a woman clad in diaphanous, off-the-shoulder drapery. Her pose is at once relaxed and assertive: one arm rests behind her, while the other gracefully traces a pendant at her throat. Above her head, a circular mandorla motifs a mosaic pattern in muted gold and green that evokes stained glass or a jewel’s faceted surface. The mandorla frames her head like a halo, emphasizing her embodiment of the gemstone’s qualities. The panel’s upper corners feature irregular, painterly washes in earthy tones, offering a subtle counterpoint to the graphic precision of the figure and flowers.

Line as Structural Principle

Line is the foundational element in Mucha’s visual language, and in The Ruby it functions both structurally and decoratively. The figure’s contours—her shoulders, neckline, and arms—are defined by bold, unbroken strokes that give solidity to her form. Within these outlines, secondary lines articulate the folds of her drapery and the curl of her hair, varying in weight to suggest depth and movement. The floral petals are carved with a combination of sweeping curves and angular accents, their edges outlined in dark strokes that separate them from the background. In the mosaic mandorla, geometric lines interlock to create stars and polygons, introducing a layer of precise linear ornamentation. Mucha’s modulation of line weight—heavy contours balanced by delicate hatchings—imbues the image with rhythmic vitality, as if the very essence of the ruby is pulsing through every curve.

Color and Light

Although Mucha’s palette often favored pastel hues, The Ruby embraces a warmer, richer spectrum to capture the gemstone’s fiery spirit. The dominant reds of the floral foreground range from deep carmine at the petal bases to brighter crimson at the edges, mirroring the gradations of a polished ruby. These reds contrast vividly with the pale ivory of the figure’s drapery, which carries subtle pink undertones. Her skin is rendered in delicate peach and cream tones, allowing the ruby accents—the floral jewels in her hair and necklace—to stand out even more brilliantly. The mandorla’s mosaic employs muted gold and olive green tesserae, whose reflective quality suggests the internal glow of a gemstone’s facets. Soft shadows under the figure’s chin and within the floral petals lend three-dimensional modeling, while highlights on the necklace and the folds of cloth capture the play of light across smooth surfaces.

Symbolism and Allegory

In The Ruby, Mucha weaves multiple layers of symbolism. Rubies have long symbolized passion, vitality, and protection, and these qualities are personified in the figure’s poised yet languorous stance. Her direct gaze, slightly tilted head, and half-smile convey both confidence and allure, suggesting the stone’s associations with love and desire. The large red flowers at her feet evoke the ruby’s origins in alluvial deposits—nature’s hidden treasures borne to the surface by geological forces. In her hair and necklace, smaller ruby-like gems dangle like fruits, reinforcing the notion of generosity and abundance. The mosaic mandorla overhead functions as a sacred emblem, linking the earthly bounty below with a transcendent realm above. Through this rich symbolism, Mucha transforms the gemstone’s physical properties into a complex allegory of human emotion and cosmic harmony.

Ornamental Motifs and Decorative Integration

Much of The Ruby’s visual impact comes from its intricate decorative motifs. The stylized flowers combine naturalistic veining with abstracted shapes, their petals almost rhythmic in their repetition. The drapery knots at the figure’s waist echo the flower petals’ folds, creating a visual resonance between human attire and botanical form. The mosaic-inspired halo introduces radial symmetry and reinforces the theme of polished facets. In the panel’s upper corners, painterly washes break the geometric precision, incorporating an Art Nouveau tension between controlled ornament and spontaneous gesture. This juxtaposition of precise linework and free-form brushwork showcases Mucha’s ability to balance graphic clarity with painterly nuance, ensuring that the rhetoric of decoration never overwhelms the central figure’s presence.

Technical Execution and Medium

Executed in color lithography, The Ruby demonstrates Mucha’s command of both draftsmanship and printmaking processes. His studio prepared full-scale cartoons, indicating color separations for each lithographic stone—reds for the flowers and gems, pale flesh tones for the figure, and muted greens and golds for the mosaic halo and background washes. Skilled lithographers transferred these separations onto limestone or metal plates, requiring precise registration to align the multiple layers. The stippled skin tones and delicate cross-hatching in the drapery demanded fine gradations that lithography could accommodate when expertly handled. The final prints retained both the brightness of the reds and the subtle translucency of the figure’s garb. Mucha’s attention to technical detail ensured that each printed edition would carry the same vibrancy and decorative richness as the original design.

Interaction of Figure and Environment

A hallmark of Mucha’s work is the seamless integration of figure and environment, and in The Ruby this interplay adds narrative depth. The figure emerges from the floral foreground as if rising from the earth itself, her dress and hair intertwining with the vines and blossoms. The mosaic halo, while symbolic, also serves as a decorative backdrop that anchors the figure within a defined space. The upper painterly areas—tinted in ochre and sienna—suggest natural settings such as rustling leaves or a sunlit sky at dusk, reinforcing the figure’s connection to elemental forces. This dynamic interaction—where human form, decorative pattern, and suggested landscape converge—immerses the viewer in an all-encompassing world of Art Nouveau beauty.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Beyond its decorative allure, The Ruby possesses a potent emotional resonance. The figure’s direct, almost challenging gaze invites a personal encounter: the viewer becomes an active participant, drawn into her world of passion and mystery. The warm color palette evokes feelings of comfort and intensity in equal measure, while the rhythmic lines and floral motifs create a gentle visual melody that soothes the eye. Mucha understood the psychological power of decorative art: by engaging viewers on a sensory level—through color, pattern, and symbolic imagery—he elicited a deeper emotional response than mere entertainment. In The Ruby, art and emotion coalesce, offering an experience that feels both sensuous and spiritually uplifting.

Comparative Analysis with Mucha’s Other Gemstone Panels

When compared to Mucha’s other gemstone panels—such as Emerald or Amethyst—The Ruby stands out for its bold embrace of warm hues and its emphasis on floral dynamics. While Emerald employs cooler greens and leafy motifs, and Amethyst uses violet tones with crystalline shapes, Ruby’s red palette and filamentous flower forms convey heat and movement. Each panel in the series maintains Mucha’s characteristic figure-or-ornament integration, yet The Ruby pushes the decorative rhetoric further by featuring oversized petals that almost break the panel’s lower boundary. This comparative perspective highlights Mucha’s ability to adapt his formal vocabulary to the specific qualities of each gemstone, ensuring that every panel feels both unique and part of a cohesive whole.

Reception and Exhibitions

Contemporary audiences greeted The Ruby and its companion panels with enthusiasm. Exhibitions of Mucha’s decorative works attracted both art connoisseurs and the broader public eager for the latest Art Nouveau sensations. Critics praised the series for its innovative fusion of allegory and ornament, noting how Mucha’s designs elevated decorative panels to the status of narrative painting. Collectors sought out printed editions, while the original lithographs became fixtures in salons and parlors. Over time, the gemstone series solidified Mucha’s reputation not only as a poster artist but also as a versatile decorative painter whose influence extended across multiple genres.

Influence on Decorative Arts and Modern Design

The legacy of The Ruby and Mucha’s gemstone panels can be traced through subsequent developments in decorative arts, graphic design, and even branding. Designers of the early twentieth century drew upon his integration of figure and ornament, and manufacturers commissioned similar allegorical imagery to promote luxury goods. In the mid-century revival of Art Nouveau motifs, Mucha’s work experienced renewed appreciation, influencing typography, interior design, and fashion prints. Today’s graphic designers and illustrators continue to study The Ruby for its masterful use of line, color harmony, and ornamental balance, adapting its principles to digital media and contemporary branding projects.

Preservation and Scholarly Study

Original prints and preparatory sketches for The Ruby are held in museums and private collections worldwide. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing lithographic inks and preventing paper degradation. Scholars analyze Mucha’s technique through archival research, microscopic pigment analysis, and digital imaging, uncovering insights into his studio methods and his collaborations with lithographic workshops. Exhibitions on Art Nouveau, decorative painting, and Mucha’s oeuvre consistently feature The Ruby, recognizing it as a touchstone for understanding the movement’s central tenets and the artist’s transformative impact on early twentieth-century visual culture.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s The Ruby stands as a paragon of Art Nouveau decorative art—an image in which allegory, symbolism, and ornamental mastery coalesce into a transcendent whole. Through its dynamic composition, masterful line work, rich color palette, and layered symbolism, the panel not only celebrates the ruby’s passionate vitality but also embodies Mucha’s belief in art’s capacity to enrich daily life. More than a decorative panel, The Ruby offers an immersive experience—a sensuous interplay of figure and flower, of light and line—that continues to captivate viewers more than a century after its creation. In this work, Mucha proves that even the most luxurious ornament can bear profound emotional and cultural significance, affirming art’s enduring power to inspire wonder and delight.