Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

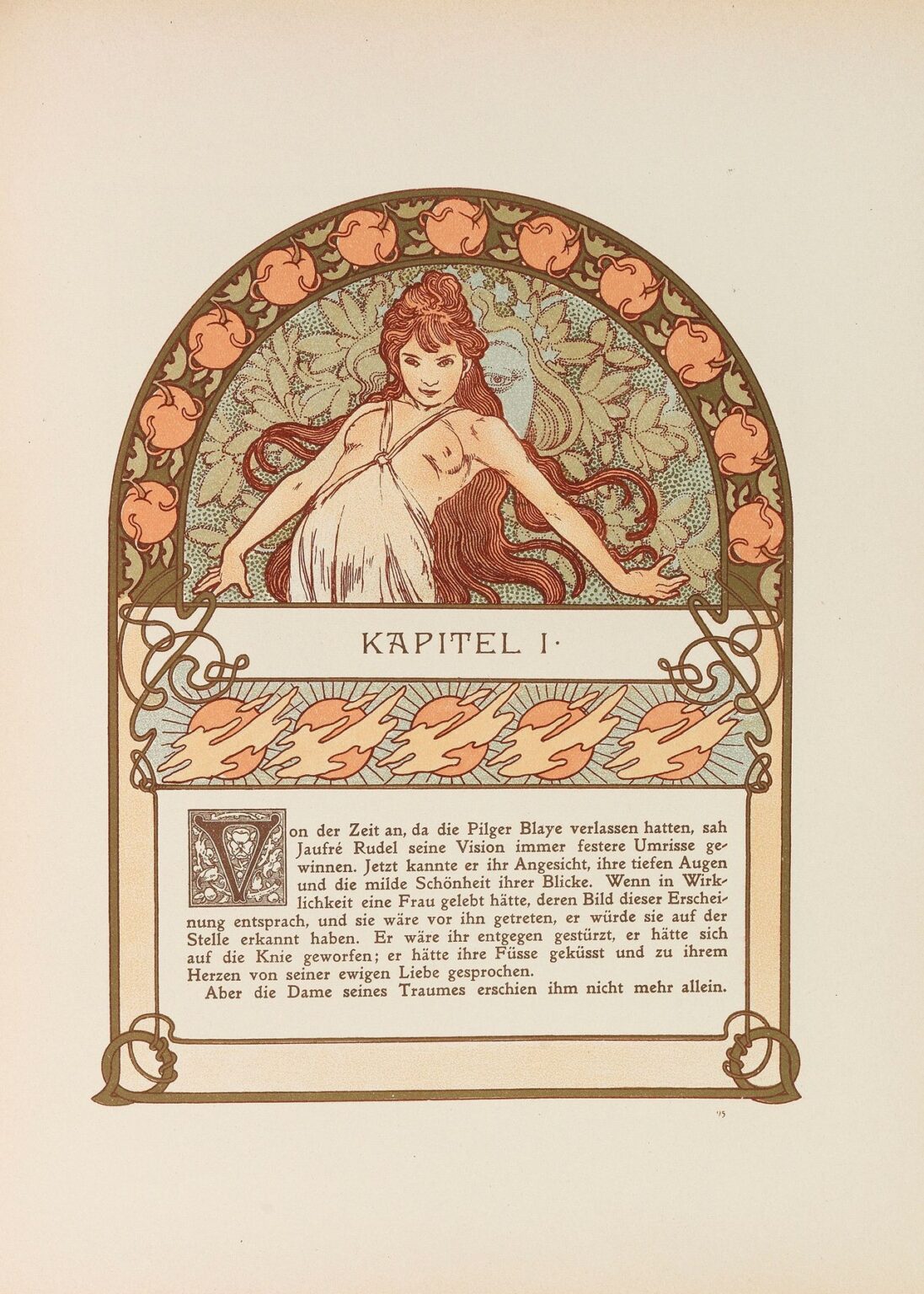

Alphonse Mucha’s Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli (1901) stands as an emblematic synthesis of medieval romance and Art Nouveau elegance. In this oval-format composition, Mucha casts a luminous young woman at the forefront, her visage framed by flowering motifs and ornamental drapery. The princess’s serene countenance and flowing hair evoke tales of chivalric devotion and exotic courts, while the sinuous lines and pastel palette reflect Mucha’s signature decorative vocabulary. As both a narrative portrait and a decorative panel, Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli invites viewers into a mythic realm where legend and ornament intertwine seamlessly.

Historical Context

At the turn of the twentieth century, European art was in flux. The academic academies still celebrated historicist painting and grand religious subjects, yet the avant-garde embraced new influences from Japanese prints, medieval craftsmanship, and nature’s organic forms. Paris, where Mucha achieved early fame through theatrical posters, served as a nexus for this transition. His breakthrough came in 1894 with the lithograph Gismonda, after which he became a leading figure in the Art Nouveau movement. By 1901, the demand for decorative art had grown to encompass everything from jewelry to wallpaper. Within this context, Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli reflects both the period’s fascination with romantic medievalism and Mucha’s commitment to infusing fine art with ornamental beauty.

Mucha’s Artistic Evolution

Although Mucha is best remembered for his poster work, he continuously sought to expand his practice into painting, illustration, and design. His posters showcased elongated female figures set against floral halos and curving arabesques. In the early 1890s, he began to transpose these stylistic hallmarks onto easel paintings, experimenting with oil and pastel. Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli represents a mature instance of this crossover. The work retains the rhythmic contours and decorative borders of his graphic pieces while employing painterly modulation in flesh tones and atmospheric backgrounds. Mucha’s ability to navigate between commercial commission and personal artistic vision is evident in the way this painting balances narrative depth with ornamental composition.

Commission and Subject

Although documentation of the original commission is sparse, Mucha’s choice of subject aligns with the era’s revived interest in chivalric and orientalist themes. Tripoli—an ancient Mediterranean port—evoked images of Crusader romances, Ottoman intrigue, and the fertile lands of the Near East. By inventing a character named Ilsée, Mucha tapped into the popular taste for medieval allegory. The princess appears both regal and vulnerable: her rich white robe and floral wreath signal aristocratic privilege, yet her slightly downcast gaze and relaxed posture humanize her. In this way, Mucha offers not a static emblem but a living persona whose story unfolds through subtle narrative cues.

Composition and Framing

Mucha employs a gently rounded arch to frame Ilsée, drawing directly from medieval architectural motifs and his own poster designs. This arch, bordered by a ring of pomegranate-like blossoms against olive foliage, functions as a halo of nature, elevating the princess to an almost sacred status. Within this frame, the central figure leans forward, her arms extending beyond the lower boundary, breaking the picture plane and creating a sense of immediacy. Negative space above her head provides balance, while the dense cluster of blooms behind her reinforces the protective enclosure. The careful calibration of symmetry and dynamism imbues the composition with both stability and movement.

Use of Line and Ornament

Line serves as the structural backbone of Mucha’s decorative art. In Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli, every contour—from the princess’s jawline to the curling tendrils of her hair—is defined with precise, flowing strokes. The pomegranate blossoms and their curling vines mirror the S-curves of her drapery, creating a visual echo that unifies background and figure. Fine hatching in the foliage and the soft stippling behind the blossoms lend textural richness without detracting from the overall clarity. The ornamental filigree in the lower corners frames the narrative text—if this painting were part of an illustrated tale—pointing to Mucha’s interest in book design and integrating illustration.

Color and Light

Mucha’s palette in this work combines warm earth tones with cool accents. The princess’s pale flesh glows against the warmer ivory of her robe, while her auburn hair and the peach-toned fruits in the border lend warmth. Subtle green-blue shadows in the foliage and the lightly glazed background suggest ambient daylight filtered through leaves. Mucha applied thin glazes of oil to achieve transparent luminosity in the robes, contrasting with opaque passages in the blossoms and vines. Highlights on petal edges and the princess’s cheek capture hints of reflective light, creating a gentle three-dimensionality that complements the flat decorative planes.

Symbolism and Allegory

Behind its decorative veneer, Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli is rich in symbolic reference. Pomegranates symbolize fertility and prosperity and were often associated with royal iconography, hinting at Ilsée’s dynastic role. The wreath of white blossoms she wears may allude to purity and virtue, echoing medieval crowns of innocence. Her half-profile suggests contemplation rather than confrontation, implying introspection or longing. The floral arch functions as both garden and protective emblem, evoking the hortus conclusus motif of medieval Marian imagery. By weaving these symbols into a secular portrait, Mucha invites viewers to reflect on themes of duty, desire, and the intertwining of personal and collective histories.

Technical Execution

Executed in oil on board, the painting likely began with a full-scale cartoon, followed by an underpainting to establish major color zones. Mucha used sable and hog-hair brushes to alternate between broad washes in the background and fine detail in the border. He built up flesh tones through multiple glazes of lead white mixed with small amounts of ochre and red, allowing the inner layers to glow. The minute stippling in the background involved a fine chisel brush, capturing a sense of depth without resorting to heavy chiaroscuro. Throughout, Mucha maintained a smooth surface, avoiding pronounced impasto so that the decorative motifs remained crisp and clear.

Integration with Decorative Arts

Mucha’s painting extends beyond the canvas to influence decorative art in multiple disciplines. The pomegranate and vine motif seen here appears in his designs for jewelry, textiles, and ceramics. Interior decorators in Central Europe adopted these patterns for wallpapers and friezes, integrating Mucha’s iconic style into domestic spaces. Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli thus exemplifies how his painted panels could inform broader design vocabularies, reinforcing his vision of total art that encompassed architecture, furniture, and even stage design.

Emotional Resonance

Central to the painting’s impact is the princess’s blend of poise and introspection. Her gentle lean, downcast gaze, and slightly pursed lips suggest a moment of personal reflection amid the splendor of her courtly surroundings. Viewers sense her awareness of duties unspoken—perhaps the pressures of alliance, the pangs of forbidden love, or the weight of dynastic expectation. Mucha’s refined handling of expression—achieved through subtle modeling around the eyes and mouth—imbues Ilsée with a psychological depth that transcends her decorative context.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its unveiling, Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli found favor among collectors of Art Nouveau and enthusiasts of medieval revival. Critics noted Mucha’s skill in harmonizing narrative content with pure decoration, praising the painting’s seamless integration of allegory and aesthetic beauty. In the decades that followed, the panel inspired book illustrators and poster artists who sought to emulate its melodic lines and symbolic richness. Today, it remains a touchstone in studies of Mucha’s mature style, exemplifying his capacity to infuse fine art with the ornamental vitality he pioneered in commercial graphics.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli stands as a testament to his ability to unite narrative portraiture with the flourishes of Art Nouveau ornament. Through its harmonious composition, refined handling of line and color, and layered symbolism, the painting transports viewers into a mythic world of medieval romance and exotic allure. Ilsée herself emerges as a figure of grace and mystery, embodying both personal introspection and the grandeur of her imagined court. This panel not only enriches our understanding of Mucha’s artistic evolution but also reaffirms the power of decorative art to convey profound emotional and cultural narratives.