Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

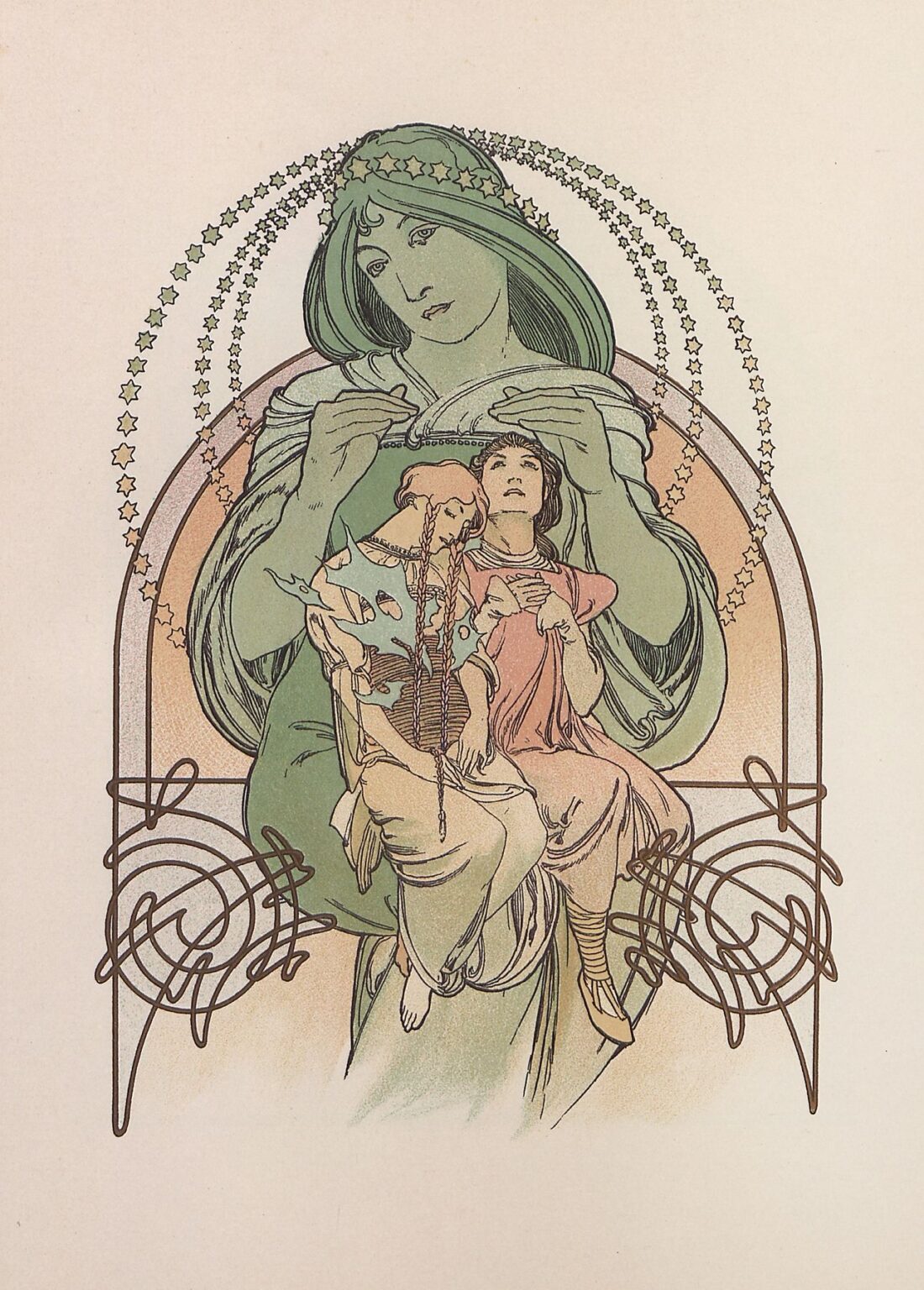

“Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli,” painted by Alphonse Mucha in 1901, exemplifies the artist’s transition from celebrated graphic designer to accomplished easel painter. At first glance, the work reveals Mucha’s signature Art Nouveau style—graceful curves, decorative motifs, and harmonious color relationships. Yet on closer inspection it transcends mere ornamentation, offering a profound exploration of character, narrative, and painterly technique. The princess occupies the center of the composition with serene dignity, her visage framed by an arch of stars that both celebrates her royal status and hints at larger cosmic themes. This painting invites viewers into a rich visual world where legend, symbolism, and human emotion converge beneath the smooth surface of oil paint.

Historical Context

The dawn of the 20th century marked a period of artistic upheaval in Paris, where avant-garde movements challenged academic conventions inherited from the École des Beaux-Arts. Art Nouveau emerged as a counterpoint to academic historicism, drawing inspiration from natural forms, Japanese prints, and medieval craftsmanship. Artists, designers, and architects sought to create Gesamtkunstwerk, or total works of art, unifying fine art, applied arts, and architecture into coherent environments. Alphonse Mucha arrived in Paris in 1887, initially making his mark through lithographic posters that revolutionized commercial advertising. By 1901, he leveraged his decorative expertise to pursue painting commissions that allowed greater narrative depth. “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli” thus reflects both the public appetite for exotic medieval romance and the era’s emphasis on integrating decoration into all aesthetic realms.

Art Nouveau and Mucha’s Artistic Vision

Mucha’s vision was rooted in the belief that art should enrich everyday life, dissolving the boundary between ornament and function. His posters featured haloed female figures surrounded by floral halos and undulating lines, an approach that brought fine art to theater facades, shop windows, and periodicals. In transitioning to canvas, he retained this decorative impulse while expanding his painterly vocabulary. In “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli,” the elaborate linear patterns of vines, stars, and drapery folds testify to his mastery of ornament. Yet the work also displays a refined command of chiaroscuro, atmospheric perspective, and tonal modulation more commonly associated with academic painting. Mucha achieved a synthesis of his graphic stylization and the three-dimensional depth that only oil painting could provide, demonstrating his versatility across media.

Commission and Narrative Origin

Although the precise patron and circumstances of the commission remain undocumented, Mucha’s choice of subject signals his interest in medieval and orientalist themes popular among Parisian audiences at the time. Tripoli, an ancient Mediterranean city, evoked associations of Crusader romances, caravan trade routes, and sumptuous eastern courts. By inventing a princess named Ilsée, Mucha tapped into a fertile vein of storytelling that combined chivalric legend with exotic allure. The princess’s composed expression and lavish attire suggest she belongs to a world of ceremony and destiny, yet her slightly downcast eyes convey introspection and perhaps concealed longing. Mucha granted viewers just enough narrative breadcrumbs—the starry halo, the jeweled clasps on her robe, the throne-like cushion—to spark curiosity without prescribing a specific storyline.

Composition and Design

Mucha’s compositional strategy revolves around a gently rounded arch that frames Ilsée’s head and shoulders, a motif he often used to integrate figures into decorative settings. This arch, composed of concentric lines and punctuated by five-pointed stars, serves both as a visual halo and a structural boundary. Within this space, the princess’s profile tilts subtly to the viewer’s right, introducing a diagonal that energizes the symmetrical framing. Vertical folds of drapery cascade around her torso, their serpentine rhythms echoing the linear grace of her hair and the arabesques below. Mucha balances these dynamic curves with carefully measured negative space at the corners, preventing the design from feeling crowded. The result is an image that feels both expansive and concentrated, drawing the viewer’s gaze toward Ilsée’s contemplative face.

Use of Line and Form

Line functions as the lifeblood of Mucha’s decorative approach. In “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli,” the contours of the princess’s face and hands are defined by confident, unbroken sweeps, while finer hatchings model her cheekbones and chin. Her hair falls in parallel arcs, the individual strands outlined with precision that nonetheless retains an organic fluidity. The stars in the arch are rendered as delicate outlines, their repeated geometry contrasting with the irregular curves of the drapery. Beneath the figure, two swirling arabesques anchor the composition, echoing the S-curves of the princess’s sleeve and skirt hem. These ornamental lines do not merely delineate form; they create a visual rhythm that animates the surface and unites figure and decoration in a seamless whole.

Color Palette and Light Interaction

Mucha’s color choices in this painting demonstrate a mature tonal sensibility. He employs a restrained palette of sage green, dusty coral, warm ochre, and muted gold, evoking both the sands and sunlit waters of the Mediterranean. Ilsée’s skin is rendered in luminous ivory tones, built through thin glazes that allow underlying layers to glow. Shadows along her neckline and beneath her arms carry cool undertones of gray and umber, providing depth without harsh contrast. Highlights on her star halo and the metallic clasps of her robes catch light with an almost sculptural clarity. The background remains intentionally neutral, a subtle gradient that shifts from pale cream at the top to warm beige at the bottom, ensuring that the figure emerges with crisp definition while remaining integrated into the overall harmony of hue.

Symbolism and Allegory

The painting’s symbolism operates on multiple levels, blending historical romance with universal themes. The arch of stars suggests divine sanction, implying that Ilsée’s rule and destiny are written in the heavens. Stars have long served as metaphors for guidance, aspiration, and the impermanence of human endeavors; their presence here may hint at the princess’s hope or the cosmic forces that shape her fate. The princess’s elaborate robes, fastened by jewel-like buttons and metal clasps, signify aristocratic privilege and the weight of ceremonial duty. Yet her gentle expression and downcast eyes hint at inner vulnerability, suggesting that her regal poise conceals personal doubts or desires. Mucha deftly embeds these layers of meaning without resorting to overt narrative props, trusting viewers to engage actively with the work’s enigmatic undertones.

Technical Process and Materials

Executed in oil on canvas, “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli” likely began with a detailed underdrawing in charcoal or thin paint, establishing the principal contours and proportions. Mucha then applied a neutral imprimatura layer to unify the surface tone and lend warmth to subsequent glazes. Flesh tones were developed through multiple thin layers of pigment mixed with medium, allowing light to penetrate and reflect from within. Drapery and decorative elements were painted over these groundwork layers, using a combination of soft brushes for smooth transitions and firmer brushes for crisp outlines. Minimal impasto—limited to the brightest highlights on stars and jewelry—ensures that the overall finish remains smooth and decorative, in keeping with Mucha’s graphic roots. A final varnish would have deepened shadow passages and saturated the color harmonies.

Interaction with Architecture and Display

Though painted as an easel work, the composition of “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli” reveals Mucha’s sensitivity to architectural context. The arch framing device echoes the windows and doorways of medieval and Islamic architecture, suggesting that the painting could have been designed for integration into a decorative panel or mural scheme. In salon or gallery settings, the work’s vertical format and ornamental margins would complement carved wood panels, stained glass windows, or mosaic friezes. Mucha’s experience designing interiors and decorative objects likely informed his approach, ensuring that the painting could function as both a standalone image and part of a larger decorative ensemble. The seamless blend of figuration and ornament demonstrates Mucha’s holistic vision of art as an environment-enhancing force.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Central to the painting’s impact is Ilsée’s direct yet introspective gaze. While her profile positions her within a mythic framework, her eyes engage the viewer with a hint of human vulnerability. The slight downturn of her mouth and the subtle tension in her eyebrows suggest contemplation or melancholy, inviting viewers to speculate on her inner life. Mucha’s balanced composition and harmonious palette create a soothing visual experience, yet the underlying emotional complexity adds a layer of depth that rewards sustained observation. Viewers find themselves oscillating between admiration of decorative beauty and empathy with the princess’s concealed feelings, forging an intimate artistic dialogue across time and context.

Comparative Analysis with Mucha’s Other Works

When contrasted with Mucha’s iconic posters—where bold outlines and vibrant color contrasts serve commercial aims—“Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli” reveals a different facet of his artistry. The painting privileges tonal subtlety over graphic immediacy, chiaroscuro modeling over flat color fields. Yet decorative motifs—arches, haloed heads, trailing arabesques—remain consistent across both genres. In comparison to his stained glass designs, which rely on lead cames and colored glass to articulate line and hue, the canvas version substitutes pigment and brushwork to achieve a similar ornamental integration. By examining these works together, one appreciates Mucha’s capacity to translate his decorative imagination across diverse media, adapting his core aesthetic principles to the unique demands of each form.

Conservation and Influence

Over a century after its creation, “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli” continues to resonate with audiences and artists interested in the synthesis of narrative and ornament. Conservation efforts have stabilized its delicate glazes and prevented darkening of varnish layers, ensuring that the original color relationships remain visible. The painting’s influence extends beyond Art Nouveau revivalists to contemporary illustrators and designers who seek to merge figure drawing with decorative patterning. Its legacy also informs academic discourse on the relationship between popular graphic art and so-called “fine” art, challenging strict hierarchies by demonstrating how commercial and decorative impulses can enrich traditional painting.

Conclusion

In “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli,” Alphonse Mucha achieves a masterful balance of decoration, narrative, and painterly finesse. The painting’s harmonious composition, refined color palette, and sinuous lines embody the ideals of Art Nouveau while offering a deeply human portrayal of a fictional princess. Through her serene yet introspective gaze, viewers are drawn into a timeless story of duty, destiny, and personal longing. Mucha’s seamless integration of ornamental and pictorial elements testifies to his lifelong commitment to unifying art and life. As both a stunning decorative panel and an evocative portrait, “Ilsée, Princess of Tripoli” remains a testament to the enduring power of beauty, symbolism, and craftsmanship.