Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

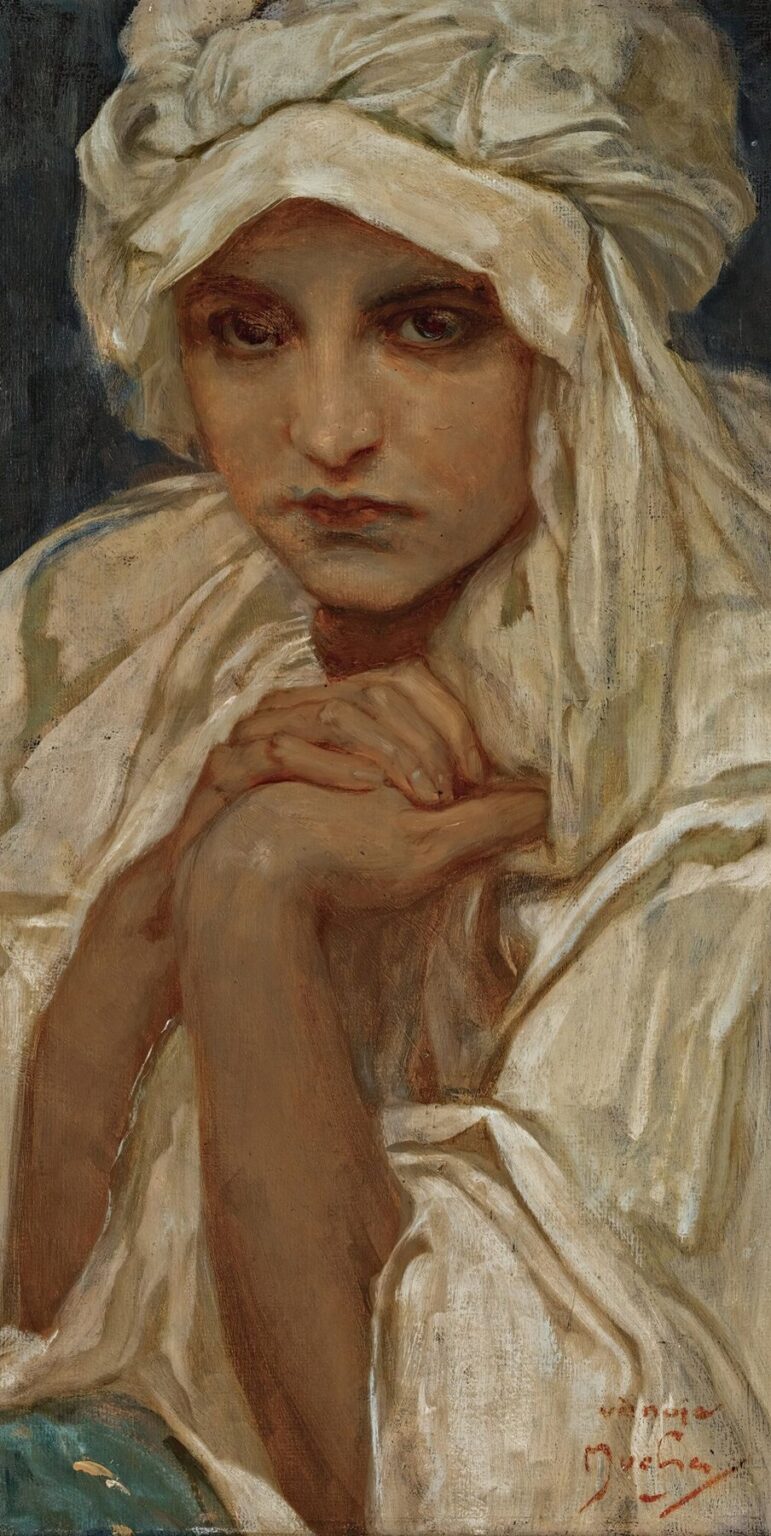

Alphonse Mucha’s Portrait of a Girl exemplifies the artist’s transition from decorative poster-maker to accomplished portraitist, capturing both the aesthetic ideals of the fin de siècle and a deeply personal, psychological intimacy. Painted in the early 20th century, this work departs from the elaborate Art Nouveau ornamentation for which Mucha was renowned, embracing instead a spare, contemplative approach to portraiture. The young woman—her head draped in a white turban, her gaze steady and introspective—occupies nearly the entire vertical plane of the canvas, creating an immediate sense of presence. Mucha’s delicate interplay of light and shadow, combined with his subtle modulation of line and brushwork, transforms a simple likeness into an evocative study of character. In this analysis, we will examine the historical backdrop of the painting, Mucha’s evolving artistic vision, the work’s compositional strategies, its chromatic subtleties, and the psychological resonance that cements its place in the artist’s oeuvre.

Historical Context

By the turn of the 20th century, Paris had become the epicenter of artistic innovation, with movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau all vying for prominence. Born in 1860 in Moravia, Alphonse Mucha arrived in Paris in 1887 and initially supported himself as a decorative artist and graphic designer. His breakthrough came in 1894 with the celebrated poster of Sarah Bernhardt in Gismonda, which propelled him to the forefront of Art Nouveau. Yet even as he gained fame for his sinuous lines and ornate floral motifs, Mucha remained keenly aware of the evolving currents in European painting. By the 1900s, portraiture and allegorical painting held renewed interest among Symbolist and academic circles. In this climate, Mucha’s Portrait of a Girl emerges as an intriguing synthesis: it retains the decorative sensibility of Art Nouveau while probing more serious, introspective subject matter.

Alphonse Mucha’s Artistic Evolution

Mucha’s early Paris years were marked by an intense focus on lithography and design. His signature style—graceful women crowned by halos of blossoms, rendered in pastel tones—redefined advertising graphics and decorative arts. However, in the first decade of the 20th century, Mucha began to explore more painterly genres, including allegorical canvases and formal portraits. He sought to demonstrate that his talents extended beyond the commercial sphere, aspiring to the grand traditions of history painting and portraiture. Portrait of a Girl thus represents a deliberate pivot. While traces of his linear elegance remain, the emphasis shifts to painterly modulation: the soft rendering of flesh, the nuanced depiction of fabric folds, and the subtle reflections of interior light. In doing so, Mucha aligned himself with contemporaries who valued psychological depth and atmospheric subtlety.

Purpose and Commission

Although the precise circumstances of the commission remain obscure, it is likely that Portrait of a Girl was created for a private patron or family who desired an intimate, timeless likeness of a loved one. Unlike his large-scale decorative panels, this portrait is small enough to hang in a domestic interior, fostering a personal encounter. The lack of overt symbolic attributes—no elaborate jewelry, no overt floral motifs—suggests that Mucha intended to focus attention on the sitter’s face and hands, the primary conveyors of character. The choice of a white turban and draped garment may have been both practical and aesthetic: white reflects ambient light, allowing Mucha to explore tonal variations, while the head covering alludes to Renaissance portraiture, evoking an artistic lineage that transcends contemporary fashion.

Composition and Framing

Mucha composes the portrait vertically, filling nearly the entire frame with the girl’s figure. This close cropping eliminates background distractions and intensifies the viewer’s focus on the sitter’s gaze and gestures. The head wraps toward the left, while the subject’s eyes meet the viewer head-on, creating a gentle tension between sideways inclination and frontal engagement. The hands, clasped lightly beneath the chin, form a triangular axis that anchors the composition and conveys a sense of poised contemplation. Mucha balances this intimate scale with subtle negative space: the dark, undefined backdrop emphasizes the illuminated figure, while the folds of the white fabric create rhythmic vertical and diagonal lines that echo the girl’s long, slender neck.

The Play of Line and Brushwork

Although renowned for his precise, decorative line work, Mucha demonstrates a different approach in Portrait of a Girl. Here, line is subordinated to painterly modeling: the contours of the face and hands emerge from gradations of tone rather than from heavy outlines. In areas such as the hair’s edge and the fabric’s creases, slight lines lend definition, but they never dominate the form. Brushstrokes remain visible, particularly in the white drapery, where loosely applied, translucent layers of paint capture the memory of textile folds. This freer handling contrasts with his poster work, signaling Mucha’s embrace of painterly technique. Yet even as the brush moves more fluidly, his hand remains controlled, ensuring that each stroke contributes to the overall harmony of the image.

Color Harmony and Light

Mucha employs a restrained palette in this portrait, centered on warm flesh tones, creamy whites, and muted earth colors. The white turban and drapery serve as both a reflective surface and a unifying element, bouncing soft light onto the subject’s features. Shadows are rendered in cool grays and umbers, creating a subtle chromatic contrast that models the face and hands in three dimensions. The eyes, regions of deepest tone, draw attention with their dark intensity, while the lips—a muted rose—provide a gentle focal point within the pale face. This careful orchestration of warm and cool hues enhances the sitter’s naturalistic presence without resorting to overt coloristic effects. The overall harmony evokes a quiet luminosity, as if the portrait were bathed in diffused, interior sunlight.

Symbolism and Iconography

Unlike Mucha’s allegorical panels, Portrait of a Girl offers no overt symbols to decode. Instead, the portrait invites reflection on the universality of youth, introspection, and quiet dignity. The white turban may hint at themes of purity or rebirth, echoing the iconography of medieval and Renaissance portraiture, but it remains ambiguous enough to avoid didactic readings. The sitter’s direct gaze and slightly furrowed brows convey both confidence and vulnerability, suggesting an inner life that extends beyond the canvas. By eschewing elaborate props or backgrounds, Mucha relies solely on the subject’s expression and posture to convey meaning, trusting the viewer to find resonance in the subtle interplay of form and feeling.

Technical Execution and Medium

Executed in oil on canvas (or panel), Portrait of a Girl showcases Mucha’s mastery of traditional painting techniques. He likely began with an underdrawing to establish major forms, then applied a transparent ground layer to unify the surface. Flesh tones were built through successive glazes, allowing light to penetrate and reflect back through the paint, creating a glowing effect. The white fabrics were painted with mixtures of lead white and a small amount of umber to avoid harsh brilliance, while shadows incorporated blue and gray pigments to maintain tonal unity. Mucha’s delicate handling of edges—softening transitions in facial planes while preserving sharper demarcations at the turban’s border—demonstrates his deep understanding of optical effects. The resulting surface balances smooth modeling with visible painterly gesture.

Psychological Presence and Emotional Depth

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of Portrait of a Girl is its psychological immediacy. The sitter’s open, slightly melancholic eyes seem to hold secrets, engaging the viewer in an unspoken dialogue. Her hands—fingers gently interlaced—suggest a moment of quiet reflection or hesitant anticipation. Mucha’s sensitive rendering of these gestures conveys a gentle tension: poised but not rigid, reserved yet open to engagement. The absence of a narrative context amplifies this psychological depth, as the viewer is invited to project their own emotions onto the portrait. In this way, the painting transcends mere likeness to become a mirror of universal human introspection, a hallmark of effective portraiture.

Comparative Analysis with Mucha’s Other Works

When compared to Mucha’s flamboyant poster compositions—brimming with elaborate borders, floral halos, and vivid color contrasts—Portrait of a Girl feels refreshingly understated. Yet it shares the same devotion to the female gaze and to the elevation of women as subjects of beauty and contemplation. Unlike his large allegorical panels, which often portray mythic or symbolic figures, this portrait emphasizes realism and personal presence. In this respect, the work aligns more closely with the academic portraits of his era, while still retaining a trace of his decorative lineage in the treatment of hair and drapery. The transition between these genres illustrates Mucha’s versatility and his ambition to be recognized beyond the confines of commercial art.

Reception and Legacy

Although Portrait of a Girl did not achieve the wide public exposure of Mucha’s posters, it garnered praise in academic and private circles for its refined skill and emotive power. Collectors admired the painting’s blend of decorative elegance and personal intimacy, viewing it as evidence of Mucha’s broader artistic range. In subsequent decades, art historians have cited the work as a key example of the artist’s foray into traditional painting genres. Exhibitions that focus on Mucha’s lesser-known canvases often include this portrait to illustrate his dual identity as both decorative designer and serious painter. Its quiet charisma continues to captivate modern audiences, inspiring contemporary artists who seek to combine graphic sensibility with psychological portraiture.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Portrait of a Girl stands as a testament to the artist’s evolution from Art Nouveau luminary to accomplished portraitist. Through its harmonious composition, painterly delicacy, and psychological immediacy, the work transcends simple representation to become a profound meditation on presence and introspection. Mucha’s restrained palette and subtle modulation of light underscore the sitter’s individuality, while the absence of overt symbolism invites viewers to engage their own emotions. In embracing the challenges of traditional portraiture, Mucha demonstrated the breadth of his artistic vision and secured a lasting legacy in the history of early 20th-century art.