Image source: artvee.com

Overview of “Laurel” by Alphonse Mucha

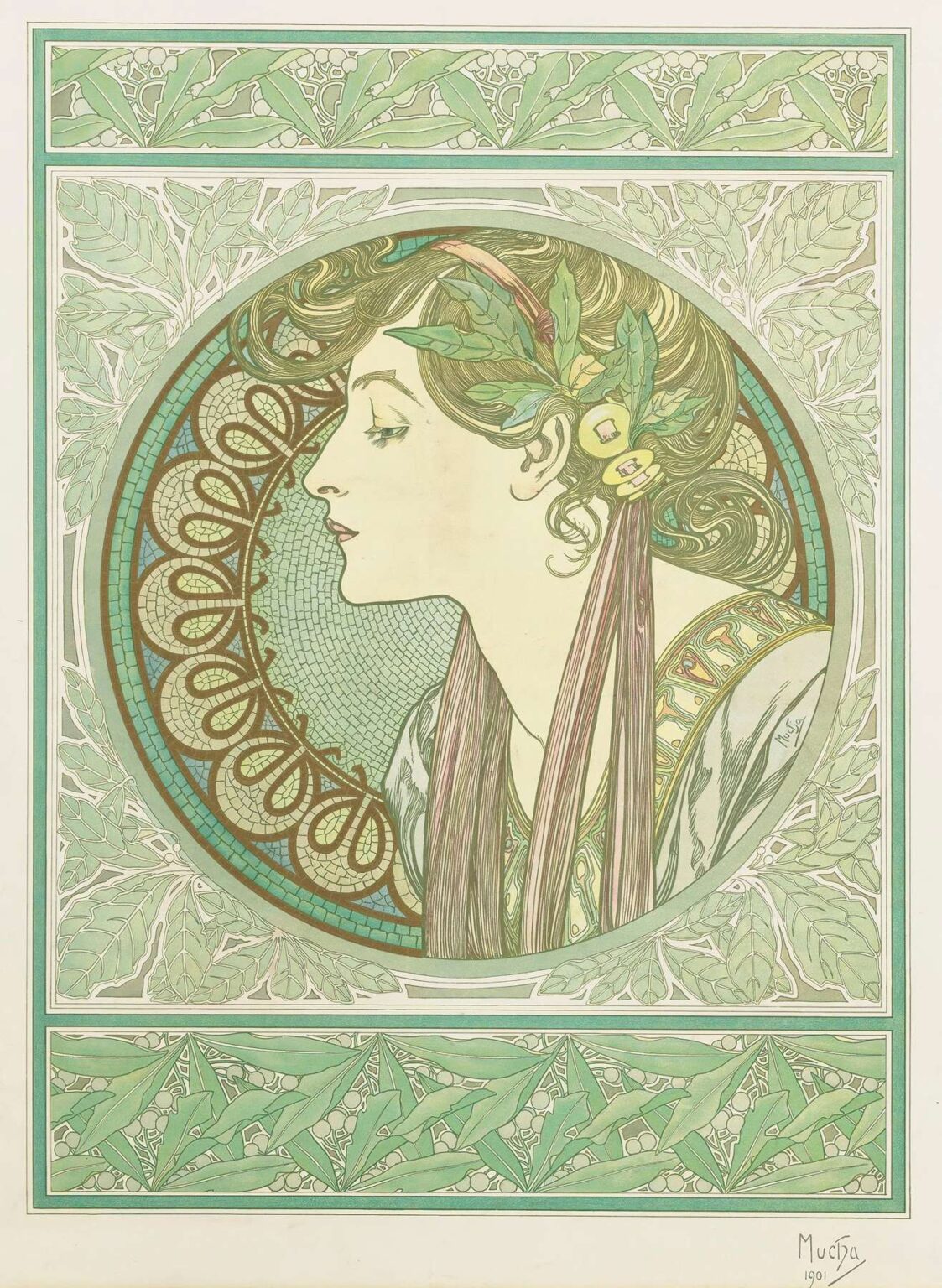

“Laurel” (1901) stands as one of Alphonse Mucha’s most refined decorative panels, epitomizing the harmony of figure, ornament, and allegory that defines his mature Art Nouveau style. Rendered as a limited‑edition lithograph, the work presents a serene female profile encircled by a wreath of laurel leaves, set against a subtly textured circular medallion. Above and below, finely detailed friezes of stylized foliage echo the laurel motif, while geometric corner ornaments mark the transition between the figure and the frame. Mucha’s deft integration of sinuous line, muted color washes, and ornamental geometry transforms a simple botanical symbol into a poetic evocation of victory, peace, and poetic inspiration.

Historical and Cultural Context

At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris was the crucible of Art Nouveau, a movement that sought to unite fine art and applied design through organic forms and a total‑work‑of‑art ethos. Posters, bookplates, and decorative panels proliferated as both commercial advertising and objects of aesthetic contemplation. By 1901, Mucha had achieved international acclaim for his theatrical posters, product advertisements, and decorative cycles. His floral and allegorical panels responded to a growing demand among collectors for art prints that could adorn private interiors. “Laurel” emerges from this milieu as a commission likely intended for refined domestic display, showcasing Mucha’s ability to create imagery that is at once decorative, symbolic, and deeply rooted in the artistic currents of the Belle Époque.

Alphonse Mucha’s Artistic Development to 1901

Mucha’s journey from Bohemian painter to Parisian master navigator of lithography shaped the evolution of his style. Early successes in 1894–1896 with Sarah Bernhardt posters catapulted him into the limelight, leading to commercial commissions for brands like JOB cigarettes and Bénédictine liqueur. By the late 1890s, Mucha was equally invested in private decorative work, producing series such as The Seasons and The Flowers. “Laurel” represents the culmination of his exploration into botanical allegory: the figure is no longer confined by commercial text; instead, she inhabits an ornamental realm where line, form, and meaning coalesce in a quietly triumphant celebration of nature’s beauty.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Mucha frames “Laurel” within a portrait‑orientation rectangle, softened at the top corners by arched transitions into ornamental friezes. The central figure—a young woman in profile—occupies the circular medallion at the composition’s heart. Her placement along the golden vertical axis establishes a sense of balance and poise. Horizontal registers above and below provide decorative counterweights, ensuring the viewer’s eye moves fluidly from the detailed botanical patterns to the figure’s contemplative gaze. Slight overlaps of the circular frame with the ornamental bands blur the boundaries between form and decoration, reflecting Mucha’s belief in the seamless integration of all design elements.

Depiction of the Allegorical Figure

The woman in “Laurel” embodies classical serenity and modern stylization. Her profile recalls ancient medals and cameo portraits, with a straight nose, gently curved lips, and a refined chin. Mucha models her flesh with minimal hatching, relying on the purity of flat ivory washes to suggest smoothness and youth. Her coiffure—loose tendrils counterbalanced by a low chignon—anchors the laurel wreath at her brow. The wreath’s leaves, rendered in varied greens, denote victory, honor, and poetic inspiration. Through her composed expression and classical posture, Mucha individualizes the allegory, inviting the viewer to contemplate the virtues symbolized by laurel rather than the figure’s personal identity.

Symbolism of Laurel in Art and Myth

The laurel leaf has deep roots in Western iconography as a symbol of triumph, poetic genius, and divine favor. In ancient Greece, victorious athletes and poets were crowned with laurel wreaths, honoring excellence and inspiration. By adopting this symbol, Mucha connects his modern decorative art to a venerable lineage of classical allegory. In “Laurel,” the wreath encircles the figure’s head like a halo, suggesting an inner radiance born of creative achievement and moral virtue. The botanical friezes further reinforce this symbolism, with repeated laurel motifs reminding viewers of the cyclical nature of honor and renewal. Mucha thus transforms a simple plant into a potent emblem of artistic aspiration.

Line Quality and Decorative Rhythm

Mucha’s mastery of line permeates every aspect of “Laurel.” Bold contours delineate the figure and frame, while finer, calligraphic strokes articulate hair locks, leaf veins, and ornamental scrolls. The circular wreath behind the figure features a rhythmic repetition of lobed patterns, echoing the organic curves of the laurel leaves and the figure’s flowing hair. Horizontal bands of stylized foliage use precise outlines and minimal shading to create a banded rhythm that complements the circular motif. Through these interconnected curves and angles, Mucha establishes a visual symphony in which each line leads gracefully to the next, guiding the viewer’s gaze in an endless loop of discovery.

Color Palette and Technical Lithographic Process

“Laurel” employs a restrained yet evocative color scheme that underscores its allegorical theme. Soft greens—ranging from pale sage to deeper olive—dominate the wreath and friezes, while warm neutrals and creams accentuate the figure’s skin and background. Wisps of rose and gold highlight her garments and the wreath’s berries, adding gentle vibrancy without disrupting the overall calm. Realizing these subtle gradations and metallic hints required complex multi‑stone lithography. Mucha collaborated closely with the F. Champenois workshop, specifying color separations and transparency values. Each ink layer—line, key tonal fill, halftone washes, and metallic accent—was printed from a dedicated stone, demanding precise registration and expert inking to preserve the design’s delicate integrity.

Background Treatment and Spatial Depth

Unlike many of his commercial posters, where backgrounds often remain flat to emphasize the subject, Mucha introduces a measured sense of depth in “Laurel.” The circular medallion behind the figure features a tessellated mosaic pattern that recedes subtly, suggesting an inlaid architectural element. Beyond this circle, the background is treated with a pale, near‑neutral wash, allowing the central motif to stand forward. The ornamental bands framing the scene float against this neutral field, creating layers that enhance the panel’s three‑dimensional illusion. Through this sparing use of tonality, Mucha balances the flat decorative surface with a gentle spatial structure.

Decorative Borders and Their Significance

Mucha’s belief in the unity of form and decoration is evident in the panel’s meticulously crafted borders. The upper and lower registers display stylized botanical friezes: a repeating pattern of laurel leaves, buds, and blossoms interconnected by sinuous stems. Executed in light green outlines over a cream ground, these friezes bookend the central image, reinforcing the laurel motif while providing visual pauses. The corner ornaments, with their geometric arabesques, transition seamlessly between the friezes and the main frame, underscoring the integrity of the overall design. By weaving decorative borders into the narrative of the piece, Mucha ensures that no element feels superfluous; each part contributes to the allegorical meaning.

Light, Shadow, and the Illusion of Form

While “Laurel” is primarily decorative, Mucha employs delicate shading to suggest form and movement. The figure’s shoulder, neck, and collarbone receive faint tonal modeling—achieved through sparing crosshatching and halftone lithographic plates—that lends sculptural solidity. The laurel leaves display subtle gradients from mid‑green to pale highlights, implying curvature and light reflection. The robe’s fabric, rendered in soft washes of cream and gold, shows gentle folds and translucency. These touches of chiaroscuro enrich the panel’s tactile presence without undermining its graphic clarity, allowing the viewer to appreciate both the decorative pattern and the figure’s dimensionality.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Mucha’s “Laurel” invites contemplative engagement through its serene beauty and layered symbolism. The figure’s composed profile and the wreath’s timeless emblem speak of dignity, poetic inspiration, and triumph of the human spirit. The harmonious color palette and rhythmic ornament foster a sense of calm and balance. Viewers are drawn into the quiet world of the early spring goddess, invited to reflect on the ideals of excellence and creative renewal that the laurel represents. Each viewing reveals new visual pleasures—the subtle interplay of line and color, the delicate texture of the lithographic surface, the echoing patterns of leaf and curl—ensuring that the work retains its power to enchant.

Influence on Later Decorative Arts

Though one of Mucha’s less commercial panels, “Laurel” had a lasting impact on decorative arts and graphic design. Its integration of allegory, botanical motif, and border ornament inspired textile designers to adopt laurel‑leaf patterns in lace and embroidery. Architects and interior decorators echoed its medallion framing in mosaic inlays and stained‑glass windows. Graphic designers looked to its fusion of figure and ornament when creating bookplates, journal covers, and product labels in the Art Nouveau and subsequent Art Déco periods. Mucha’s approach—elevating a single botanical symbol to universal metaphor—continues to inform the work of illustrators and brand designers seeking to evoke heritage and refinement.

Conservation and Modern Reception

Original prints of “Laurel” are considered rare treasures within Belle Époque collections. Their early lithographic papers and ink layers require specialized care—UV‑filtered lighting, stable humidity, and acid‑free mounting—to prevent fading and brittleness. High‑resolution digital reproductions have broadened access for scholars and design students, while museum exhibitions on Art Nouveau regularly feature “Laurel” to illustrate Mucha’s decorative mastery. Contemporary retrospectives emphasize its role in bridging fine art and commercial design, reaffirming its status as more than a decorative print but as a pivotal expression of turn‑of‑the‑century aesthetics.

Technical Collaboration and Mastery

The realization of “Laurel” demanded precise collaboration between Mucha and the lithographers at F. Champenois. Multi‑stone lithography was a painstaking process: line work, key tonal plates, color overlays, and metallic accents each required separate stones and careful registration. Mucha’s detailed drawings specified color tints and shading values, guiding printers in matching the subtle gradations of his original watercolors. The workshop’s skill ensured that the final print retained the crispness of Mucha’s contours and the luminosity of his washes. This technical mastery produced a finish that balanced painterly effects with the graphic boldness essential to Art Nouveau design.

The Role of Typography

In contrast to his commercial posters, Mucha includes minimal text in “Laurel”—only his signature and the date discreetly placed in the lower right corner. This restraint underscores the panel’s decorative purpose. Elsewhere in his career, Mucha had experimented with integrating elaborate custom letterforms into his compositions. Here, the absence of dominant typography allows the imagery to speak for itself. The result is a work that functions as pure visual poetry, free from promotional copy, reinforcing Mucha’s conviction that art should uplift the everyday viewer without the baggage of overt commercial messaging.

Legacy and Continuing Influence

Over a century after its creation, “Laurel” remains a touchstone for designers and art historians exploring the interplay of nature, allegory, and ornament. Its themes of inspiration, achievement, and renewal resonate in contemporary branding—where laurel wreaths still symbolize excellence—and in editorial illustration that seeks to fuse classical references with modern aesthetics. The panel’s formal innovations in framing and background treatment continue to inspire illustration classes and design studios. As both a decorative object and a work of enduring poetic power, Mucha’s “Laurel” exemplifies the timeless appeal of Art Nouveau’s union of beauty and meaning.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Laurel (1901) stands as a radiant embodiment of Art Nouveau’s decorative heights. Through the poised profile of an allegorical figure, the sacred symbolism of the laurel wreath, and the seamless integration of botanical ornament and geometric framing, Mucha crafts a work of serene power. Its harmonious palette, fluid line, and subtle spatial depth invite sustained contemplation, while its technical virtuosity in multi‑stone lithography affirms the artist’s mastery. More than a decorative panel, “Laurel” celebrates the ideals of victory, creative inspiration, and the quiet majesty of nature’s cycles—an invitation to marvel at beauty’s many facets.