Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Composition

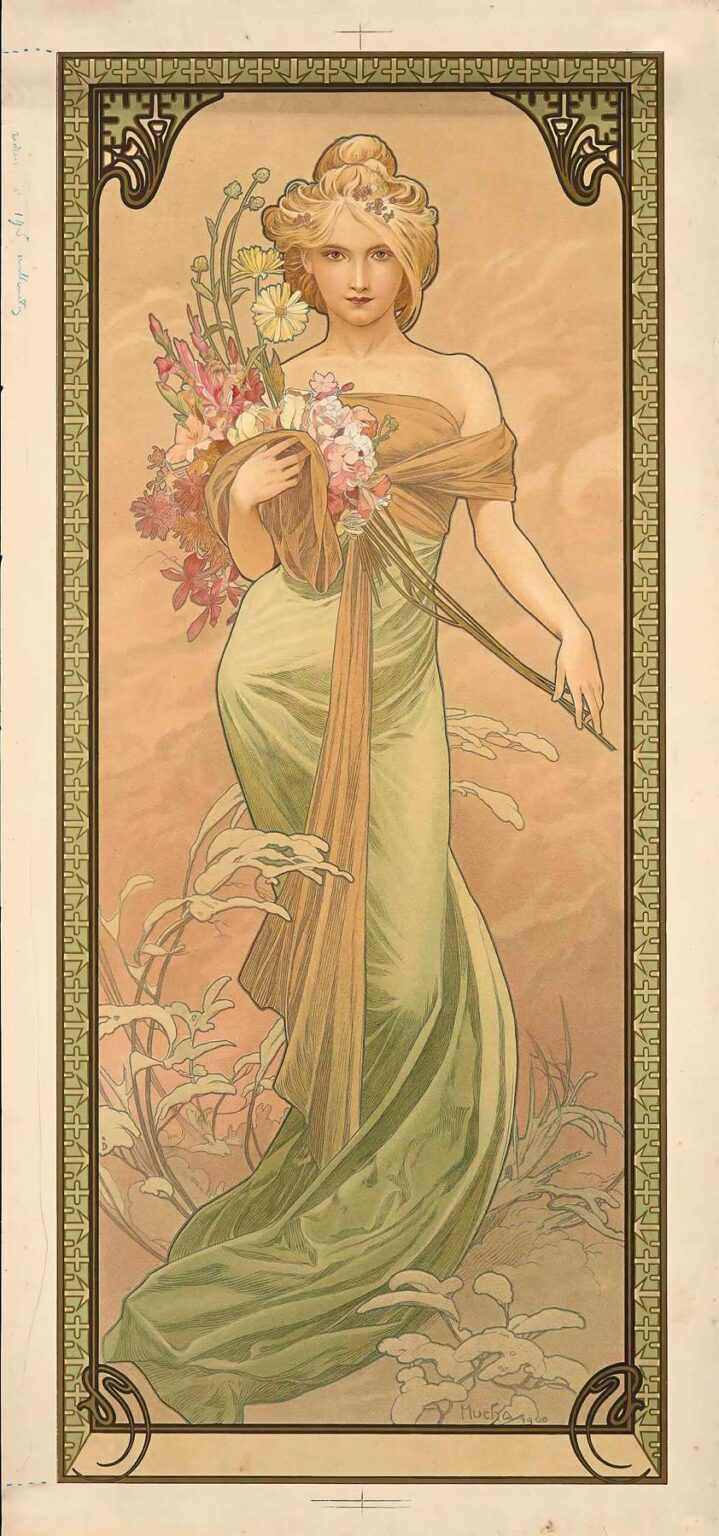

Spring (1900) by Alphonse Mucha epitomizes the artist’s Art Nouveau vision, transforming a simple seasonal theme into an ornate allegory of renewal. Designed as one of six panels personifying the seasons, Spring presents a standing female figure draped in a flowing green gown, her blonde hair crowned with delicate blossoms. She cradles a lush bouquet of buds and flowers in her left arm while her right hand elegantly extends a single stem. Enclosed within a tall, narrow frame adorned with stylized geometric patterns and organic motifs, the figure appears poised between earth and sky. Mucha’s masterful integration of figure, floral symbolism, and decorative framing creates an immersive celebration of nature’s rebirth.

Historical and Cultural Context

At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris was the epicenter of avant‑garde art and design. The Belle Époque era celebrated progress, leisure, and aesthetic innovation. Art Nouveau, with its emphasis on natural forms and sinuous lines, emerged as a reaction against industrial mass production and historicist revivalism. Mucha’s work captured this spirit by elevating everyday objects and commercial posters into high art infused with organic ornament. His seasonal panels, created in 1900 for private collectors, extended the reach of Art Nouveau into decorative interiors. Spring, in particular, resonated with contemporary fascination for symbolism, the cycle of nature, and the feminine ideal as bearer of renewal.

Alphonse Mucha’s Career in 1900

By 1900, Alphonse Mucha had become synonymous with the Art Nouveau movement. His breakthrough 1894 poster for Sarah Bernhardt led to commissions for theater, luxury brands, and publications. Over the next six years, his Paris studio produced iconic works for JOB cigarettes, Moët & Chandon, and Bénédictine. Simultaneously, Mucha developed his personal decorative projects—flower panels, allegorical series, and interiors for wealthy patrons. Spring marked the culmination of his experimentation with seasonal personifications, in which he combined classical allegory with modern graphic style. His technical command of multi‑stone lithography and his conviction that art should permeate all aspects of life made Spring a hallmark of his mature period.

Commission, Purpose, and Publication

Spring was commissioned by an affluent Parisian collector seeking a decorative suite for a private salon. Mucha envisioned the four‑panel set (Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter) as freestanding lithographs to be framed and displayed together. Unlike his commercial posters, these panels bore minimal text—Spring carries only the season’s name at the bottom—allowing the imagery to speak purely through form and color. Lithographic proofs were produced by F. Champenois, Mucha’s trusted Parisian printer, known for precise color registration and high‑quality pigments. Subscribers and design enthusiasts acquired the prints, which quickly became coveted examples of Art Nouveau’s decorative potential within domestic interiors.

Composition and Framing

Mucha structures Spring around a vertical format that emphasizes the figure’s elegant elongation. The tall arch frame, with its crisp corners softened by subtle curves, echoes medieval stained‑glass windows and classical niche sculpture. Within this architectural shell, the figure stands centrally, her upward gaze and extended arm creating a gentle diagonal that animates the composition. Surrounding her, the background is sparsely treated—hints of foliage and softly graded washes suggest early morning light. The frame’s border features a repeated motif of interlocking forms reminiscent of budding leaves, reinforcing the seasonal theme. This interplay of rigid geometry and organic line defines Mucha’s balanced aesthetic.

Depiction of the Female Figure

The woman in Spring embodies both ideal beauty and natural vitality. Mucha exaggerates her proportions—elongating the neck and limbs—to evoke Gothic statuary and Renaissance personifications of virtues. Yet he retains naturalistic modeling in her facial features: softly arched brows, a dignified nose, and a calm yet penetrating gaze. Her hair, arranged in an elaborate updo, is crowned with tiny blossoms that mirror those in her bouquet. The draped green gown clings and folds around her form, its fabric rendered with delicate hatch lines that suggest both texture and diaphanous lightness. Through this fusion of realism and idealization, Mucha creates an allegory of springtime’s gentle power.

Symbolism of Spring

As an allegorical personification, Spring carries rich symbolism. The green gown and floral crown signify growth, fertility, and the earth’s awakening after winter. The bouquet contains early blooms—possibly narcissus, primrose, and iris—that symbolize new beginnings and hope. The single stem she offers may represent the fragile promise of life’s renewal. The sparsely indicated foliage in the background serves as a reminder that the natural world stirs back to life at this season. By weaving these botanical references into the figure’s attire and gesture, Mucha transforms the panel into a visual poem about nature’s cyclical rebirth and the promise of warmer days.

Use of Line and Form

Line is central to Mucha’s Art Nouveau language, and Spring displays his mastery of calligraphic contour. Bold outlines define the figure’s silhouette and the architectural frame, while finer interior lines articulate drapery folds, hair curls, and petals’ veins. The botanical elements share the same rhythmic curves as the figure’s hair and gown, creating a unified visual cadence. Diagonal swaths of fabric and the bouquet’s stems counterbalance the vertical axis, injecting dynamism. Mucha’s sinuous line guides the viewer’s eye through the composition, accentuating the figure’s gentle movement and reinforcing the sense of organic growth.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s color scheme for Spring is both harmonious and evocative of the season. The dominant green of the gown shifts from pale mint to deeper olive, suggesting the variety of fresh foliage. Warm flesh tones and golden hair hues create visual warmth, while subtle touches of pink and cream in the blossoms add delicate highlights. The background gradient—from soft apricot near the horizon to a pale sky tone above—evokes dawn light. Achieving these nuanced effects required multi‐stone lithography: each hue, plus metallic accents, was printed from a separate stone. Translucent inks overlap to produce gentle gradations, and precise registration preserves the crispness of Mucha’s intricate line work.

Decorative Border and Ornamentation

Mucha’s belief in total decoration extends to Spring’s ornate border. A stylized foliate pattern—abstracted into repeating geometric modules—runs along the frame’s inner edge. This pattern, rendered in muted green and taupe, recalls both budding vines and the interlinked motifs of medieval panels. Corner embellishments, where the straight edge softens into curved filigree, echo the design’s more naturalistic elements. Mucha integrates the border seamlessly with the central image: the gown’s folds seem to sweep into the frame, and the bouquet’s stems overlap slightly with the arch, blurring the line between figure and ornament in a hallmark of his decorative method.

Light, Shadow, and Spatial Depth

Although primarily decorative, Spring suggests spatial depth through subtle tonal modeling. The figure’s torso and arms exhibit gentle shading, creating a sense of volume against the flat background. The drapery’s folds—accentuated by hatching—imply layers of translucent fabric. Background foliage is simplified into silhouette washes, receding behind the figure to enhance her prominence. The frame’s inner shadow, lightly tinted, gives the impression of a shallow niche. These selective modeling techniques lend the panel a three‐dimensional feel while preserving the graphic clarity characteristic of Mucha’s lithographs.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Mucha’s Spring invites both aesthetic delight and emotional reflection. The figure’s calm confidence—embodied in her steady gaze and graceful posture—offers reassurance of nature’s dependable cycles. The fresh green palette and floral accents evoke optimism and renewal, resonating with viewers seeking solace after winter’s gloom. Mucha’s integration of form, ornament, and symbol fosters a contemplative mood: every viewing reveals new details—the subtle texture of petals, the flow of fabric, the interplay of line and color. In this way, Spring transcends mere decoration to become a meditative celebration of life’s continual rebirth.

Influence on Decorative Arts and Poster Design

Spring contributed to the broader acceptance of Art Nouveau in decorative and commercial contexts. Its success demonstrated that lithographic prints could serve as both affordable art objects and interior adornment. Designers in textile, wallpaper, and furniture incorporated Mucha‑inspired vegetal motifs and architectural framing into their work. The approach of personifying abstract concepts—seasons, flowers, celestial bodies—in elegant female forms influenced poster art well into the early 20th century. Spring’s blend of poetic allegory and decorative precision remains a model for integrating fine art sensibility into applied design.

Conservation and Modern Reception

Original lithographs of Spring are prized by museums and collectors, yet their delicate papers and early 20th‑century inks require careful preservation. UV‐filtered lighting, controlled humidity, and acid‑free framing protect the subtle color washes and fine line work from fading or deterioration. High‐resolution digital archives and published monographs have made Spring accessible to scholars and design enthusiasts worldwide. Retrospectives on Mucha and Belle Époque graphics consistently feature this panel as a quintessential example of the era’s decorative ambitions. Its enduring popularity attests to Mucha’s achievement in creating timeless visual poetry.

Technical Mastery of Lithography

Realizing Spring demanded close collaboration between Mucha and the F. Champenois printing workshop in Paris. Color lithography at the time involved multiple limestone plates—one for each hue plus metallic pigments—and exacting registration to align them perfectly. Mucha’s original drawings included annotations for color separation and density, guiding the lithographers in achieving the delicate pastel harmonies and metallic highlights. The workshop’s technical expertise preserved the integrity of Mucha’s calligraphic lines and translucent washes, resulting in prints that rival the subtlety of watercolor paintings while offering the reproducibility of commercial printing.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Spring (1900) stands as a crowning achievement of Art Nouveau decorative artistry. Through harmonious composition, lyrical line, and a refreshing color palette, Mucha crafts an allegory of renewal that resonates across a century. The panel’s seamless integration of figure, symbol, and ornament transforms a seasonal theme into a universal celebration of life’s cycles. More than a decorative print, Spring invites us to experience the gentle promise of warmer days and the enduring beauty of nature’s rebirth—an invitation as compelling today as it was at the dawn of the twentieth century.