Image source: artvee.com

Overview of the Composition

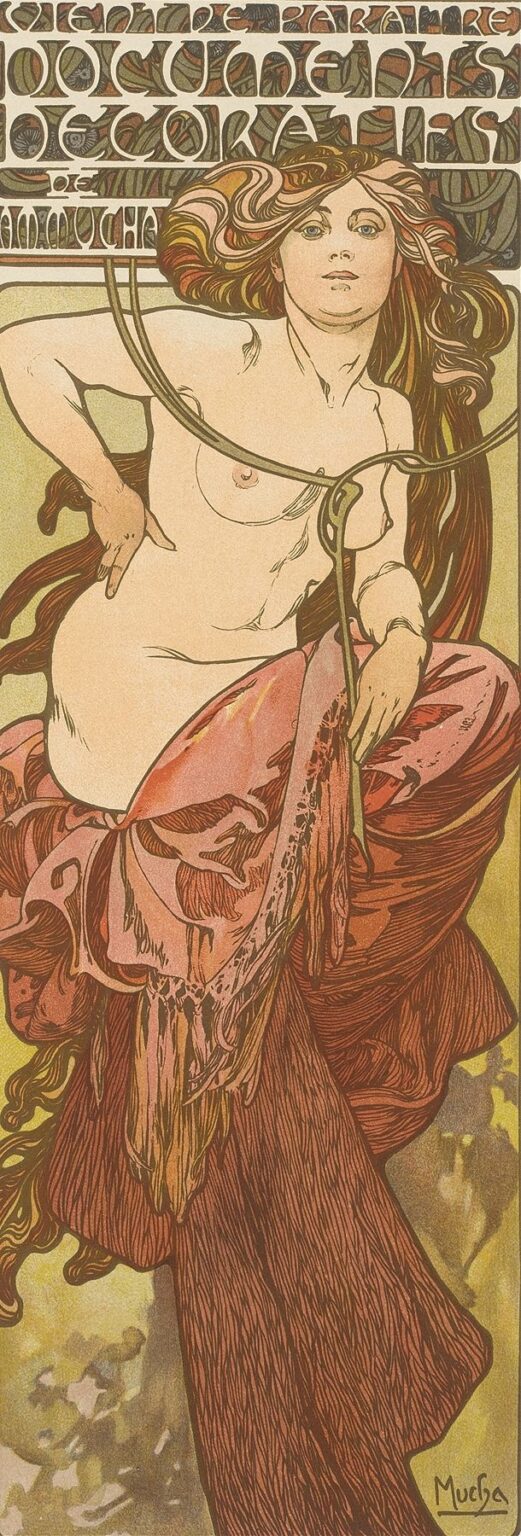

“Untitled Plate 13” (1902) by Alphonse Mucha presents a luminous vision of feminine grace set against a subtly patterned background. The vertical format accentuates the elegant posture of the central figure, whose flowing hair and draped garments create a rhythmic cascade of curving lines. The woman appears to emerge from an organic framework of undulating tendrils, as though part of a living tapestry. Mucha’s mastery of line and form is evident in the seamless transition from figure to decoration; the swirling locks of her hair entwine with the sinuous borders, drawing the viewer’s eye in a graceful spiral. The nude torso, gently modeled, conveys both vulnerability and strength, while the vibrant shawl she holds adds a note of warmth and color. This plate exemplifies Mucha’s belief that art should harmonize human beauty with decorative abstraction, inviting contemplation of both the poetic and the ornamental.

Historical and Cultural Context

Created at the height of the Art Nouveau movement, “Untitled Plate 13” reflects the early twentieth‐century fascination with the unity of fine art and applied design. By 1902, Mucha had already achieved fame through his theatrical posters and decorative panels, inspiring a generation of artists and designers across Europe. This period was marked by rapid industrialization and urban growth, which fostered a yearning for natural forms and aesthetic refinement in everyday life. Mucha responded to this sensibility by producing works that blended classical motifs, Slavic folklore, and modern ornamentation. His decorative plates—often intended for publication in luxury magazines or portfolios—served as artistic explorations free from commercial constraints. “Untitled Plate 13” thus stands as both a summation of Mucha’s decorative vocabulary and a testament to his role in shaping the visual identity of the Belle Époque.

Alphonse Mucha’s Artistic Evolution in 1902

By the turn of the century, Mucha had moved beyond purely commercial posters to create standalone decorative panels and book illustrations. His style matured into a synthesis of soft, naturalistic modeling and linear abstraction. In 1900, he completed his celebrated “The Seasons” series, demonstrating his skill in allegorical representation. Two years later, “Untitled Plate 13” reveals a heightened subtlety: the figure is less a theatrical emblem and more an icon of serene beauty. Mucha’s palette shifted toward earthier tones, and his line work grew more intricate, reflecting his deepening interest in Byzantine and folk art patterns. This plate exemplifies his transition from overt Art Nouveau flamboyance to a more refined decorative aesthetic, where every curling motif and chromatic choice serves the composition’s poetic unity.

Formal Analysis: Composition and Design

The composition of “Untitled Plate 13” is anchored by a central vertical axis, along which the figure’s spine, lifted arm, and cascading hair align. Mucha uses a looping elliptical band that encircles the figure’s upper body, creating a dynamic interplay between containment and expansion. This band, drawn with fluid precision, echoes the curves of her hair and the folds of her drapery. The background is treated as a shallow plane decorated with pale, mottled textures that resemble fresco or marbled plaster. This textured ground provides a stage for the figure without receding into deep perspective, keeping the focus on the ornamental interplay of line and form. The absence of sharp spatial recession reinforces the decorative flatness prized by Art Nouveau artists, while the carefully balanced proportions impart a sense of harmonious stability.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s color scheme in this plate centers on muted sepias, soft rose pinks, and olive greens, punctuated by richer ochres in the draped cloth. These subdued earth tones create a sense of timelessness, as though the image has been gently weathered by age. The subtle gradations in skin tone and the delicate blush on the cheeks reveal Mucha’s command of the multi‑stone lithographic process. Each hue was applied with precise registration, allowing fine filigree details to retain their sharpness against broad color fields. The artist likely used metallic mica or interference inks sparingly for highlights in the hair, lending a faint iridescence under changing light. This technical mastery ensures that the plate functions equally well as a printed collectible and as a blueprint for decorative panels or book illustrations.

Depiction of the Female Figure

The woman in “Untitled Plate 13” embodies the Art Nouveau ideal of ethereal femininity. Her posture—one arm outstretched and the other resting on her thigh—conveys both movement and repose. Mucha renders her anatomy with a delicate balance of naturalism and idealization: softly modeled shoulders and a gently arched neck suggest flesh and bone beneath the stylized surface. The slight parting of her lips and the directness of her gaze create an intimate connection with the viewer, as though she invites us into her world of quiet contemplation. Her long hair, a profusion of interwoven strands, functions almost as a living garment, trailing behind her like a river of molten bronze. This hair becomes decorative architecture, framing her face and integrating her presence into the larger ornamental scheme.

Symbolism and Iconography

While “Untitled Plate 13” lacks explicit narrative elements, its iconography speaks to universal themes of transformation and renewal. The circular band around the figure’s torso may allude to the ouroboros or the cyclical nature of life, while the entwined tendrils suggest organic growth and regenerative vitality. The minimal background evokes a liminal space—neither sky nor ground—underscoring the timeless, archetypal quality of the image. Mucha’s decorative vocabulary often drew upon Slavic folklore and Byzantine mosaics; here, the patterned textile she holds could reference traditional folk embroidery, signaling cultural continuity. The figure’s partial nudity, combined with the protective embrace of her shawl, evokes the interplay of vulnerability and shelter, suggesting a meditation on the human condition that transcends specific mythologies.

Decorative Motifs and Ornamentation

Ornamental line is the lifeblood of this composition. From the wisps of hair that spiral like tendrils to the fringe of the shawl rendered in intricate loops, every curve reinforces the work’s organic unity. Mucha’s decorative motifs—stylized leaves, curling arabesques, and concentric rings—derive from medieval manuscripts and Islamic tilework, filtered through his Romantic sensibility. These patterns do more than embellish; they structure the composition, guiding the viewer’s gaze from the figure outward and back again. Even the negative spaces between loops and locks become active participants, forming counter‑rhythms that enliven the overall design. This approach exemplifies Mucha’s credo that decoration should not be an afterthought but an integral expression of meaning and beauty.

Integration of Line and Form

Mucha’s line work in “Untitled Plate 13” demonstrates a singular fluidity. He varies line weight to suggest depth and emphasis: thicker contours define the silhouette, while hair strands and decorative filigree are drawn with fine, delicate strokes. This modulation creates a subtle hierarchy of shapes, ensuring that the viewer reads the figure first before exploring the ornament. The looping band around her midsection is executed in a continuous, unbroken line—a visual metaphor for the uninterrupted flow of natural energy. Mucha’s mastery of contour line transforms a two‑dimensional surface into a tapestry of interwoven rhythms, where delineation and decoration are indistinguishable.

Light, Shadow, and Texture

Although the plate embraces flatness, Mucha employs tonal variations to imply volume. Soft shadows along the figure’s left side and below her arm ground her form against the surface. The rendering of fabric folds incorporates both flat color fields and linear hatching, suggesting the weight and movement of cloth. The shawl’s fringe, depicted with a combination of stippling and short line marks, takes on a tactile quality. The background’s mottled texture, achieved through aquatint‑like lithographic techniques, contrasts with the crispness of the foreground, adding a painterly atmosphere. These textural contrasts enhance the sensory richness of the image, inviting viewers to imagine the touch of skin, silk, and hair.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

“Untitled Plate 13” captivates by melding sensuality with serenity. The figure’s poised yet relaxed demeanor evokes a sense of inner calm, while the surrounding ornamentation radiates subtle energy. Viewers are drawn into a contemplative space, where the boundary between subject and decoration dissolves. This immersive quality encourages repeated viewings; each encounter reveals new nuances in line, color, or pattern. Mucha’s achievement lies in creating an image that feels both personal—through the direct gaze—and universal—through the archetypal curves and symbols. The plate thus functions as a vehicle for emotional reflection, offering a moment of aesthetic escape in an increasingly industrial world.

Influence on Art Nouveau and Decorative Arts

While Mucha’s theatrical posters garnered public acclaim, plates like “Untitled Plate 13” influenced designers working in textiles, ceramics, and interior decoration. The plate’s harmonious integration of figure and ornament inspired Art Nouveau interiors, where murals and stained glass incorporated similar motifs. Graphic designers adopted Mucha’s approach to bespoke lettering and fluid line for magazine covers and bookplates. The emphasis on holistic decoration—where every surface becomes an opportunity for artistic expression—prefigured modern notions of design unity. Even today, echoes of this aesthetics appear in contemporary branding and digital illustration, testifying to the enduring power of Mucha’s decorative vision.

Conservation and Legacy

Original prints of “Untitled Plate 13” are prized by collectors and museums, yet the delicate paper and subtle inks require careful preservation. Institutions often employ low-light conditions and climate control to prevent fading and degradation. Modern reproductions in art books and digital galleries have democratized access, allowing new generations to encounter Mucha’s artistry. Scholars value the plate for its demonstration of lithographic innovation and decorative mastery at the fin de siècle. Its legacy endures not only in print collections but also in design curricula, where it exemplifies the marriage of craft and aesthetic philosophy that defined an era.

Conclusion

“Untitled Plate 13” stands as a testament to Alphonse Mucha’s conviction that art and decoration are inseparable. Through fluid lines, harmonious color, and intricate ornament, he elevates a single figure into an emblem of organic beauty and timeless allure. The plate’s balance of vulnerability and strength, its integration of ancient motifs with modern sensibility, and its mastery of lithographic technique make it a crowning achievement of Art Nouveau. Over a century later, the work continues to inspire admiration and study, reminding us that the deepest resonance of art lies in its ability to unite form and feeling in a single, radiant vision.