Image source: artvee.com

Overview of the Artwork

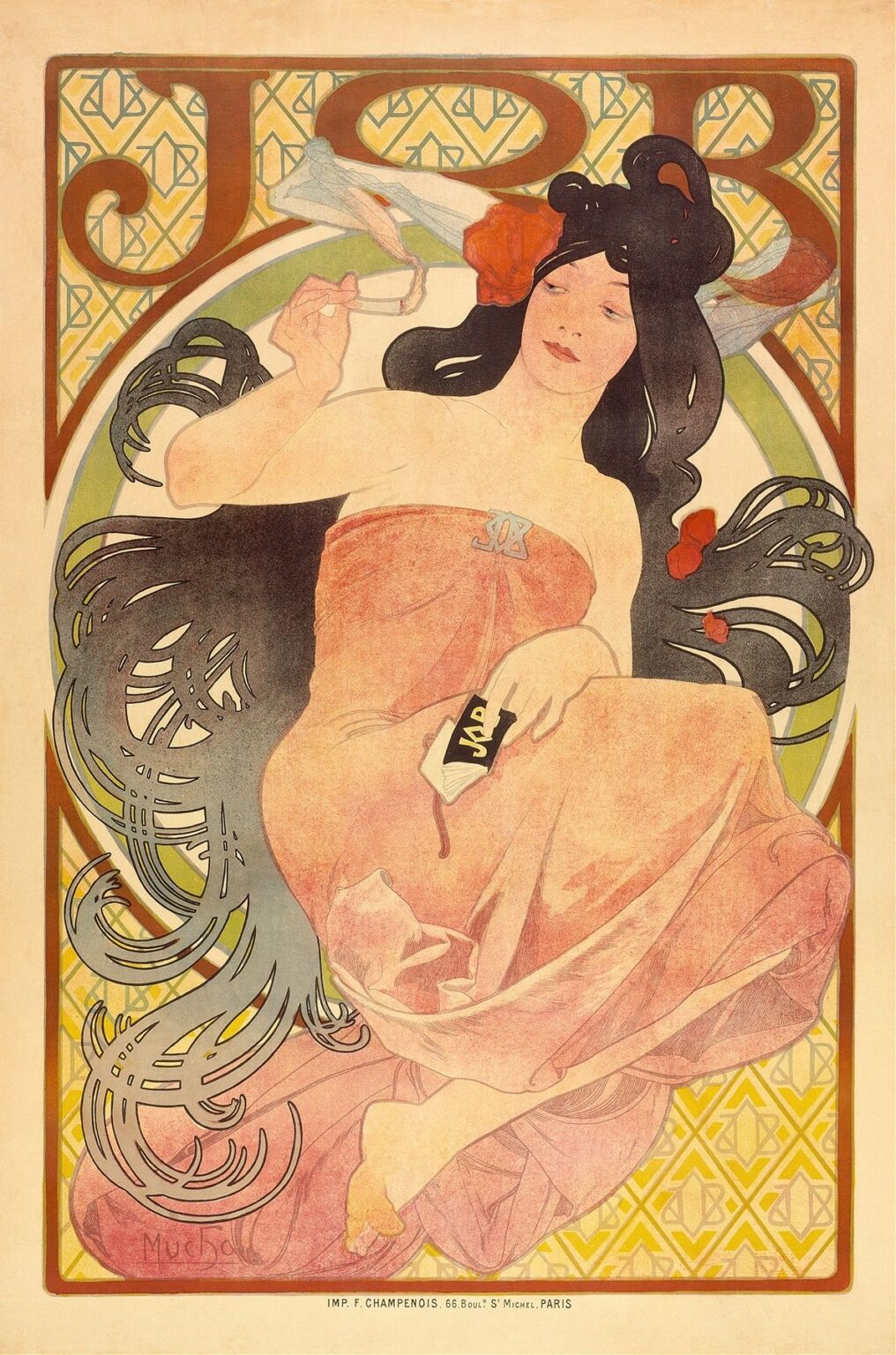

“Job” is a celebrated 1898 lithographic poster by Alphonse Mucha, commissioned to advertise Job cigarette papers. In this masterpiece of Art Nouveau, Mucha presents a graceful female figure reclining against a circular backdrop, her elongated form draped in flowing, translucent fabric. The sinuous curves of her hair, the undulating folds of her gown, and the delicate tendrils of smoke rising from the paper in her hand all converge to create a harmonious visual rhythm. Above her, the word “JOB” is rendered in bold, stylized lettering that echoes the organic loops of the decorative frame. Every element—from the patterned ground to the subtle interplay of light and shade—has been carefully orchestrated to evoke luxury, elegance, and the allure of modern leisure. The poster transcends mere advertisement, standing as a testament to Mucha’s belief in the unity of fine art and commercial design.

Historical and Cultural Context

At the fin de siècle moment when “Job” first appeared on Parisian walls, Europe was immersed in the Belle Époque—an era of optimism, technological innovation, and artistic flourishing. Public spaces had become open‑air galleries, thanks to the proliferation of color lithography, and posters were a primary means of visual communication. Mucha arrived in Paris in 1892 and quickly distinguished himself with posters for Sarah Bernhardt, but by 1898 he was equally sought after by commercial clients eager to associate their products with refined taste. The Job cigarette paper company, aiming to reposition its brand as sophisticated and modern, entrusted Mucha with the task of creating a visual identity that would captivate a discerning urban audience. In doing so, Mucha tapped into contemporary fascinations with the exotic and the ephemeral—cigarette smoke as a sensuous curl through the air, a fleeting embodiment of pleasure. The poster thus reflects both the consumer culture of its time and the aesthetic revolution that sought to dissolve boundaries between art and everyday life.

Alphonse Mucha’s Artistic Trajectory in 1898

By the time Mucha designed “Job,” he was at the height of his creative powers. Having won acclaim for his Sarah Bernhardt series (1894–1896), he developed a signature vocabulary of sinuous lines, pastel hues, and stylized natural motifs. His collaboration with printer F. Champenois enabled him to push the limits of the multi‑stone lithographic process—experimenting with metallic inks and layered transparencies to achieve unprecedented subtlety. Mucha’s work was characterized by an obsessive attention to detail: from the placement of each floral ornament to the precision of hair strands cascading across the composition. “Job” stands as a paradigmatic example of his mature style, in which the decorative and the representational coalesce seamlessly. Rather than relegating the commercial message to a small corner, he integrates brand name, product imagery, and figure into a single, cohesive tapestry—an approach that would influence poster design for decades to come.

Composition and Layout

The spatial structure of “Job” is built around a large circular motif that encloses the central figure and functions both as a halo and a decorative anchor. The reclining woman stretches diagonally from the lower left toward the upper right, guiding the viewer’s gaze along the length of her form and the curling ribbon of smoke. Her flowing hair extends beyond the circle’s boundary, creating a dynamic tension between containment and freedom. The three letters of the brand name are arrayed along the top edge, each character forming an arc that mirrors the circular frame below. This interplay of curves, arcs, and diagonals generates a sense of movement and continuity, inviting the eye to glide effortlessly from the product name to the sensual figure and back again. The composition thus balances stability with fluidity, ensuring that both the advertisement’s message and its aesthetic appeals are delivered in equal measure.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s palette for “Job” is dominated by warm apricot tones, soft rose pinks, and muted greens, set against a pale, parchment‑like ground. These hues evoke refinement and subtlety, qualities associated with the ritual of cigarette rolling and consumption. The translucent quality of the gown and the veil is achieved through successive printing of semi‑opaque inks, each layer carefully registered to avoid blurring the delicate line work. Metallic gold or mica may have been used for highlights in the jewelry and hair ornament, catching the light and lending a tactile shimmer to the image. Mucha’s multi‑stone lithography required not only artistic vision but technical mastery: each color demanded its own stone, each registration mark its own painstaking alignment. The result is a visual symphony in which color and line conspire to create depth, texture, and luminous warmth.

The Feminine Figure: Pose and Expression

The central woman in “Job” embodies the Art Nouveau ideal of feminine beauty—elongated yet sensuous, serene yet intriguing. Her eyes are half‑closed, her lips parted slightly in a moment of languid indulgence. She holds a lit cigarette paper between slender fingers, as though caught in a private reverie. The tilt of her head, the gentle flex of her wrist, and the relaxed bend of her knee convey an air of effortless elegance. Despite the stylization, Mucha’s rendering captures a believable sense of weight and gravity: the way fabric gathers at her waist, the soft transitions of light across her skin, the subtle indentation where her body meets the ground. This careful blend of naturalism and decorative abstraction allows viewers to project both desire and aspiration onto the figure, aligning the allure of the product with the timeless appeal of feminine grace.

Symbolism and Iconography

Beyond mere sensuality, “Job” is rich in symbolic resonance. The curling plume of smoke unites the figure and the product, transforming the cigarette paper into an instrument of imagination—an ephemeral medium through which the user might experience luxury and escape. The circular frame suggests a medallion or jewel, reinforcing associations with preciousness. Floral patterns woven into the border and background evoke fertility and renewal, subtly referencing the transformative act of creation—rolling one’s own cigarette paper as a ritual of personal craftsmanship. Even the brand monogram, often integrated into the woman’s jewelry or belt clasp in other works, appears here as a discreet nod to identity and exclusivity. Through these layered symbols, Mucha elevates a functional item into a talisman of modern sophistication.

Decorative Motifs and Ornamental Frame

Mucha’s genius lies in his ability to fuse figure and ornament into an indivisible whole. In “Job,” the decorative frame is not a mere border but an active visual element: its curling vines and stylized blossoms echo the arc of the woman’s hair and the spirals of smoke. The background pattern, composed of interlocking diamonds and organic forms, creates a rhythmic texture that contrasts with the figure’s soft contours. Every flourish of the filigree is drawn with the same care as the folds of fabric, blurring the distinction between decoration and depiction. This approach exemplifies Mucha’s credo of “total decoration,” in which art permeates every surface and commercial illustration aspires to the dignity of fine art. The poster thus operates on multiple levels: an advertisement, a decorative panel, and a self‑contained work of art.

Integration of Text and Image

Unlike earlier advertising posters that separated brand name from imagery, Mucha weaves “JOB” into the visual fabric of the composition. Each letter curves in harmony with the circular motif below, as though part of the same organic growth. The bold, blocky forms of the letters contrast with the sinuous lines of the figure, creating visual tension while maintaining unity through shared color accents. The typography itself is bespoke, designed specifically for this commission, and becomes as memorable as the image it crowns. This integration ensures that the poster functions on both intellectual and aesthetic levels: viewers instantly recognize the brand, yet remain enchanted by the beauty of the scene. Mucha’s pioneering method would become a hallmark of modern graphic design, where text and image operate in symbiotic relationship.

Light, Shadow, and Texture

Though essentially a flat medium, lithography can suggest three‑dimensionality through subtle gradations of tone. In “Job,” Mucha uses delicate shading to model the woman’s form: a soft shadow beneath her cheekbone, a tender highlight on her collarbone, and gentle transitions across the drapery’s folds. The fabric’s translucency—especially in the veil fluttering behind her—relies on precise control of ink density, permitting glimpses of the patterned background to show through. The luminous quality of her skin contrasts with the matte textures of the gown and the glossy sheen of her dark hair. This interplay between light and shadow not only animates the figure but also enhances the sensorial appeal of the scene, inviting viewers to imagine the tactile pleasure of soft fabric and warm skin.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

“Job” captivates not simply through technical virtuosity but by evoking an emotional narrative. Viewers are drawn into the woman’s moment of quiet indulgence, imagining themselves as confidants or witnesses to her private reverie. The ritual of cigarette rolling becomes a metaphor for leisure, self‑possession, and the small luxuries of urban life. Mucha’s image offers both aspiration and consolation: a glamorous escape from the everyday, delivered at the cost of a small piece of paper. The poster’s enduring popularity testifies to its ability to balance commercial appeal with genuine poetic allure. It invites repeated viewing, each encounter revealing new subtleties in line, color, and detail—an immersive experience that rewards both casual observers and connoisseurs.

Influence on Art Nouveau and Graphic Design

As one of the defining images of late‑nineteenth‑century poster art, “Job” shaped the trajectory of Art Nouveau and the broader field of graphic design. Its seamless integration of figure, ornament, and typography established a template for visual communication that would reverberate through the twentieth century. Designers from Vienna to New York adapted Mucha’s principles—organic forms, custom lettering, and unity of composition—to applications as diverse as magazine covers, product labels, and architectural ornamentation. The poster’s blend of craftsmanship and mass distribution anticipated later developments in branding and marketing, proving that commercial illustration could achieve the status of high art. Even today, echoes of Mucha’s style can be found in advertising, packaging, and digital media, attesting to the poster’s lasting legacy.

Conservation and Legacy

Original prints of “Job” are prized by collectors and museums, valued not only for their aesthetic beauty but also for their historical significance. Early lithographs are vulnerable to light‑induced fading, making careful preservation essential. Institutions employ specialized framing, UV‑filtered glazing, and climate‑controlled display cases to protect the delicate inks and paper substrate. Modern reproductions, in print and digital form, have democratized access to Mucha’s work, ensuring that new audiences can appreciate the poster’s elegance. “Job” continues to inspire contemporary artists and designers, who reinterpret its motifs in contexts ranging from fashion photography to digital illustration. The poster endures as a symbol of the transformative potential of graphic art—a reminder that beauty and utility need not be opposed, but can be woven together in the service of both commerce and creativity.