Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

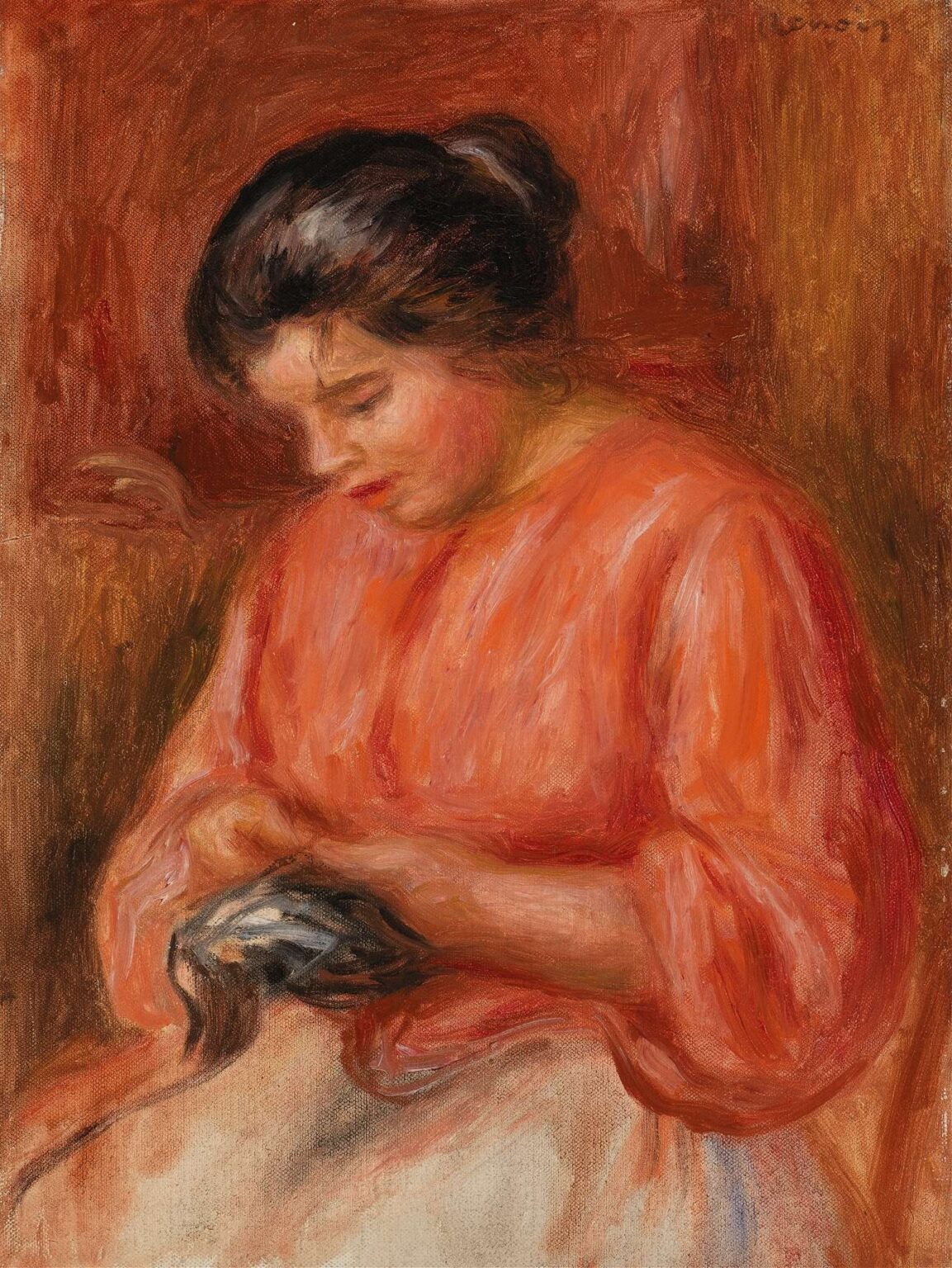

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Girl Darning (Femme reprisant), painted in 1909, stands as a luminous testament to the artist’s enduring fascination with the female figure and the quiet poetry of everyday life. Executed during Renoir’s late period—when severe rheumatoid arthritis limited his mobility yet invigorated his brushwork with tender deliberation—this intimate portrait captures a young woman absorbed in the humble yet essential task of mending fabric. Through shimmering broken color, warm tonal harmonies, and a composition that balances stillness with organic movement, Renoir transforms a commonplace domestic activity into a celebration of tactile beauty and human devotion. In what follows, we will embark on a detailed exploration of the painting’s historical context, formal design, chromatic strategy, brush technique, anatomical modeling, psychological resonance, thematic significance, technical execution, provenance, and critical legacy, thereby illuminating how Girl Darning encapsulates the mature synthesis of Renoir’s Impressionist beginnings and Classical aspirations.

Historical Context and Renoir’s Late Style

By 1909, Renoir had traversed the full arc of his artistic journey. In the 1860s and 1870s, he pioneered the radical plein‑air practice of Impressionism alongside Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley, painting ephemeral effects of light on water, foliage, and social gatherings. The 1880s saw a temporary turn toward structural clarity under the influence of Ingres and Venetian masters, as he sought greater solidity in form. Returning to a fluid, color‑driven approach in the 1890s, Renoir began integrating vibrant chromaticism with subtly modeled anatomy—a hybrid style that defined his final decades. Despite debilitating arthritis, by the early 1900s he continued to paint prolifically, sometimes strapped to his easel or working on canvases laid flat. Girl Darning emerges from this period as a prime example of Renoir’s late style: the paint surface is alive with broken strokes, yet the figure remains firmly anchored in volumetric space, embodying the artist’s lifelong commitment to the human form bathed in light.

Subject Matter and Domestic Ritual

Darning—mending holes in cloth through careful stitching—was traditionally considered both a practical necessity and a feminine rite of passage in late 19th‑ and early 20th‑century France. As mass‑produced garments became commonplace, the skill of repair took on added cultural weight, symbolizing thrift, resourcefulness, and familial care. In choosing a woman at her darning work, Renoir honors this domestic craft as an act of devotion toward sustaining the integrity of daily life. The subject’s intense focus, her hands poised above the hole in the fabric, underscores the meditative concentration and fine motor skill required. Rather than a passive, idealized beauty, the sitter is presented as active, engaged, and dignified in her labor—an homage to the quiet artistry inherent in sustaining home and family.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Renoir composes the canvas around a gently curving diagonal formed by the woman’s upper arms, shoulders, and torso. The tableau is tightly framed: the sitter nearly fills the picture plane, with the viewer’s eye drawn first to her softly bowed head, then to the flowing line of her arms as they descend to the languid folds of her coral blouse. The background dissolves into a warm, ochre‑tinged field of broken strokes, suggesting wood paneling or a sunlit interior wall, yet never specifying exact details. This ambiguity frees the figure to exist in both a particular domestic setting and a timeless realm of light and color. The diagonal axis establishes a dynamic tension between the sitter’s composed posture and the organic flow of paint across the canvas, rendering a sense of both stability and painterly vitality.

Color Palette and Light Treatment

At the heart of Girl Darning lies a harmonious interplay of warm and cool tones. The dominant hue is a coral‑rosy orange—used for the sitter’s loose‐fitting blouse—which resonates throughout the canvas in reflections on skin and background. Renoir leverages this warmth to unify figure and setting. Flesh tones are crafted from layered glazes of rose madder, Naples yellow, and zinc white, with subtle undertones of cool lavender in the shadowed recesses beneath chin and elbow. Highlights on the blouse’s creases and the sitter’s knuckles use nearly pure lead white, capturing the glint of ambient light. The background intermingles sienna, raw umber, and hints of viridian, whose muted coolness enhances the warmth of the foreground. By using complementary stretches—small dabs of pale blue beside orange, violet against yellow—Renoir achieves a vibrant scintillation that evokes sun‑riffracted interiors or the glow of a fading afternoon.

Brushwork and Surface Modeling

Renoir’s brushwork in this late portrait displays a masterful balance between controlled precision and liberating spontaneity. The woman’s face and hands—the focal points of the composition—are built through small, controlled strokes that blend softly, conveying the delicate textures of skin and bone. In contrast, her blouse is articulated through sweeping, feathered gestures that suggest the diaphanous quality of the fabric and the casual ease of her posture. The background fields are formed by energetic, curved strokes that hover between representation and abstraction. Each brushstroke remains visible, contributing to a surface texture that feels alive under shifting light. This dynamic surface invites viewers to sense the tactile quality of thread, cloth, and skin, mirroring the tactile intimacy of the act of darning itself.

Modeling of Form and Anatomical Precision

While Renoir’s technique may appear casual, his understanding of anatomy remains scrupulous. The curvature of the sitter’s shoulder, the taper of her upper arm into the subtle bend of her elbow, and the flexed tendons of her fingers all reflect careful study. Light and shadow gently define the hollow beneath the clavicle and the slight dip between arm and torso. The seated posture—leaning slightly forward—requires balance, achieved through accurate depiction of weight distribution on the hips and lower back. Renoir sculpts these volumes not with harsh outlines but through soft transitions of color: warm highlights on the collarbone and the back of the hand fade into cooler, shadowed passage along the underside of the arm. This approach yields a figure that is both tangible and suffused with the painting’s radiant atmosphere.

Psychological Nuance and Emotional Resonance

Despite the absence of direct eye contact, Girl Darning resonates with emotional depth. The sitter’s downcast gaze and slight smile—or perhaps a relaxed neutrality—suggests contentment and focus rather than introspection or melancholy. Her engagement in a purposeful task creates a quiet bond with the viewer: we, too, become witnesses to the serene concentration inherent in skilled handiwork. The restful pose and the soft luminescence of her surroundings evoke a sanctuary of domestic calm. In elevating an everyday chore to the subject of fine art, Renoir invites reflection on the dignity of labor and the meditative qualities of craft, suggesting that even the most ordinary moments possess intrinsic grace and significance.

Domestic Labor, Gender, and Social Commentary

At the turn of the century, women’s roles in the domestic sphere were both celebrated and constrained by societal expectations. Renoir’s choice to depict a woman engaged in darning both acknowledges traditional female responsibilities and subtly honors the artistry involved. The painting neither exoticizes nor sentimentalizes the sitter; instead, it accords her dignity through direct, empathetic observation. In a period when women’s labor was often undervalued, Girl Darning becomes a gentle social commentary—affirming that domestic skills deserve the same artistic consideration as leisure activities or classical themes. By focusing on a single figure and her quiet dedication, Renoir aligns himself with a democratic vision of art that finds beauty and worth in the everyday lives of ordinary people.

Relation to Renoir’s Broader Oeuvre

Girl Darning resonates with a series of domestic interiors and portrait studies that Renoir produced in the early 20th century, including Young Woman Seated at a Table (1900) and Dance at Bougival (1883) in its focus on female subjects in private settings. However, its singular focus on a solitary figure performing a domestic task distinguishes it from the more social and dynamic compositions of his earlier years. It anticipates later works like Young Woman Sewing (1911) and Mother and Children (circa 1915), in which Renoir refines his late approach: close framing, broken color, warm light, and tender humanism. In this way, Girl Darning serves as a linchpin between the evolving priorities of Renoir’s mature style and his lifelong devotion to the portrayal of women in all their individuality and grace.

Technical Execution and Conservation History

Painted on a finely woven linen canvas, Girl Darning reveals an underdrawing in charcoal that maps major contours of the figure and key folds of the blouse. Renoir then applied successive layers of paint, beginning with an ochre‑tinged ground that underlies the warm glow of the surface. The primary pigments—lead white, cadmium red, vermilion, yellow ochre, cobalt blue, and earth tones—were mixed wet‑on‑wet to achieve seamless transitions and broken color effects. Impasto highlights on knuckles and blouse folds used more concentrated pigment to capture light’s glancing sparks. Over time, a yellowed varnish had dulled some of the vibrancy; recent conservation removed this coating, applied a stable synthetic varnish, and addressed minor flaking along the canvas edges. As a result, the painting’s original luminosity and brushwork clarity have been faithfully restored.

Provenance and Exhibition History

Girl Darning was first exhibited at Galerie Durand‑Ruel in Paris in 1910, shortly after its completion, attracting praise for its warmth and technical mastery. It entered the collection of Madame Henri Martin later that year and remained in private hands until acquiring international attention during a 1925 Impressionist retrospective at the Louvre. Subsequently included in numerous exhibitions—most notably the 1956 Musée d’Orsay survey Renoir: The Humanist Impressionist—it has been celebrated as a prime example of the artist’s late domestic portraits. Now housed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., it continues to draw scholars and admirers seeking insight into Renoir’s mature integration of light, color, and lived experience.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Contemporary critics lauded Girl Darning for its luminous palette and sensitive portrayal of domestic tranquility. In the decades since, art historians have identified it as emblematic of Renoir’s late style—a period in which he distilled the lessons of Impressionism into a timeless, classical vision. Modern scholars highlight the painting’s feminist undercurrents, suggesting Renoir’s respectful treatment of female labor anticipates later explorations of gender and work in 20th‑century art. Girl Darning has influenced countless painters interested in the intersection of everyday life and aesthetic beauty, from Édouard Vuillard’s interiors to the domestic still lifes of Chardin’s inheritors. Its enduring popularity attests to Renoir’s capacity to render the ordinary as extraordinary.

Conclusion

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Girl Darning (Femme reprisant) (1909) remains a radiant jewel of his late period, merging Impressionist vibrancy with Classical poise. Through its harmonious composition, shimmering broken color, textured surface, and empathetic depiction of domestic craft, the painting transforms a simple act of mending into a moment of serene beauty. By honoring the sitter’s skill, patience, and quiet dignity, Renoir affirms the artistic value of everyday life. In Girl Darning, we witness not only the touch of a masterful painter but also the elevation of ordinary labor to the realm of fine art—a testament to Renoir’s lifelong belief in the grace that resides in human connection, light, and color.