Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

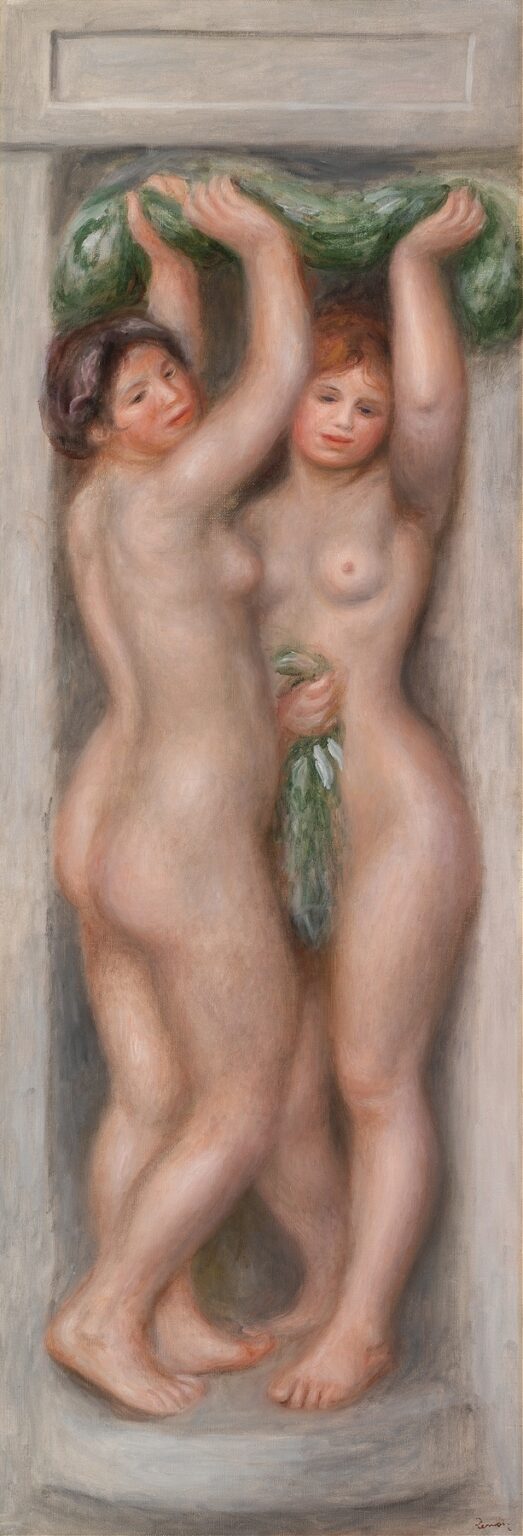

In Caryatids (Cariatides), painted by Pierre‑Auguste Renoir in 1910, the artist revisits an architectural motif that dates back to ancient Greece, transforming it into a soft, sensuous celebration of the human form. Rather than carving stone into supporting female figures, Renoir has painted two warmly modeled nude women standing side by side, their arms raised as if bearing an invisible entablature. Set against a backdrop that evokes a sculptural niche, the painting blurs the distinction between relief and fully rounded form, inviting viewers to engage with questions of volume, light, and materiality. Over the course of this analysis, we will examine the historical context of Renoir’s late style, the compositional strategies that unify architecture and figure, the nuanced chromatic harmonies and handling of light, the painter’s brushwork and surface texture, and the symbolic resonances that make Caryatids a masterpiece of late Impressionist portraiture.

Historical Context and Renoir’s Late Period

By 1910, Pierre‑Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) had traversed the full arc of the Impressionist revolution. An original exhibitor in the first Impressionist show of 1874, he spent the 1870s and early 1880s painting en plein air, capturing the flickering interplay of sunlight on water and foliage. In the mid‑1880s, he shifted toward a more structured, classical approach under the influence of Renaissance masters. His late period, roughly from 1890 until his death, is characterized by a synthesis of Impressionist colorism with a renewed emphasis on volume, line, and the tactile presence of paint. Afflicted by severe rheumatoid arthritis, Renoir adapted his technique—working on easels laid flat and strapping brushes to his deformed fingers—yet never lost his joyous command of color and brushstroke. Caryatids emerges from this final decade as a testament to Renoir’s enduring vitality and his quest to reconcile modern light effects with classical form.

The Origin and Symbolism of Caryatids

Caryatids are sculpted female figures that historically served as architectural supports in place of columns or pilasters—most famously on the Erechtheion in Athens. Traditionally, the motif evokes notions of strength, grace, and duty: the women bear a literal weight as part of a building’s structure. Renoir’s Caryatids recalls this lineage but subverts it by depicting the figures as self‑contained, unburdened by actual stonework; their raised arms imply support without the physical presence of an entablature. This playful tension between implied and actual support underscores themes of femininity, resilience, and the interplay between human flesh and architectural solidity. By painting rather than carving these caryatids, Renoir transforms them into luminous embodiments of life and light rather than static stone.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

The painting’s narrow vertical format accentuates the sense of upward extension, drawing the eye along the figures’ raised arms toward an unseen cornice. Renoir positions the two women centrally, their bodies overlapping slightly to create a stable, unified mass that nevertheless retains individual identity. The left figure turns her head toward the viewer, her gaze engaging us directly, while the right figure looks inward, as if absorbed in her own experience. Below, their intertwined legs form a subtle curve that echoes the arch of their arms, establishing a gentle S‑shaped rhythm. The background is defined by a shallow niche suggestion: a flat, gray‑beige surround that mimics stone, with a recessed horizontal panel above. This architectural allusion situates the figures within a quasi‑classical context without distracting from their living presence.

Chromatic Harmony and Color Palette

Renoir’s late palette in Caryatids is both warm and restrained. The figures’ flesh tones range from pale ivory to soft rose, with accents of peach and blush that convey blood warmth beneath the skin. Subtle green and blue reflections—borrowed from the draped cloth they hold—infuse shadows with chromatic depth rather than relying on gray alone. The cloth itself, a garland of green leaves, introduces fresh, organic hues that contrast with the muted architectural surround. Renoir avoids jarring contrasts: the background’s cool neutrals enhance the warmth of the skin, while the green cloth sits between these poles, unifying figure and setting. This carefully calibrated palette fosters an emotional tone of serenity, timelessness, and gentle vitality.

Treatment of Light and Modeling of Form

Light in Caryatids is diffuse, as though filtered through a high‐arched skylight or softly overcast sky. Renoir eschews harsh shadows, opting instead for gradations of tone that softly sculpt the figures. Highlights on shoulders, arms, and thighs are rendered in pale peach and ivory, while recesses—under the breasts, between the legs, and in the crook of the elbow—are suffused with cooler greenish grays. This ambient illumination enables a modeling of form that feels organic and three‑dimensional. The figures appear internally lit, their curves gently emerging from the canvas. The absence of strong directional light emphasizes the painting’s timeless, contemplative mood, inviting viewers to linger on the subtle interplay of light across living flesh.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Renoir’s late brushwork in this painting balances smooth modeling with tactile immediacy. The skin surfaces are built up through overlapping, blended strokes that erase the hard edge between forms—yet the texture of the brush remains visible, imparting a sense of movement within the flesh. On the green cloth, broader, more gestural sweeps capture the drape and weight of the foliage, with thicker impasto accents suggesting glossy leaves. The architectural surround is painted with thinner, more uniform strokes that mimic the grain of stone. This contrast in brushwork—differentiating organic flesh from hard architectural elements—reinforces the thematic interplay of humanity and structure. Yet across all areas, Renoir’s hand remains evident, lending the painting a unified sense of painterly vitality.

The Draped Garland: Nexus of Nature and Artifice

The garland of green leaves that the figures hold above their heads operates as a symbolic and compositional linchpin. Composed of loosely painted foliage in vibrant emerald, sage, and yellow‑green, it arcs across the top of the figures, its organic irregularity contrasting with the rectilinear niche. Symbolically, the garland evokes ideas of fertility, renewal, and festive ritual—classical associations that align with the caryatid tradition. Compositional, it guides the viewer’s eye horizontally across the canvas, linking the two figures and reinforcing their shared purpose. By introducing this natural element into an otherwise architectural framework, Renoir underscores the harmony possible between human life and built environment.

Modeling of Anatomy and Gesture

Renoir’s intimate knowledge of anatomy, gained from decades of life drawing and sculptural study, informs the realism of the bathers’ bodies. The left caryatid’s shifted weight on her right leg produces a slight contrapposto, with her left hip dipping and her torso gently twisting—details that convey believable flesh‑and‑bone structure. The right figure’s raised arms and slight turn of the head produce stretching lines along her rib cage and gentle folds of skin at her waist. Muscles and soft tissues are rendered not in harsh relief but through nuanced color shifts, capturing the softness of human flesh. This combination of anatomical accuracy and painterly subtlety places Caryatids at the intersection of naturalism and impressionistic colorism.

Architectural Allusion and Paint as Material

The painting’s framing niche suggests carved stone, yet Renoir never dips into pure monochrome: even the surround contains warm undertones and subtle variations. By deploying paint to simulate architecture, Renoir blurs the boundaries between two- and three-dimensional media. The figures appear both as painted bodies and as sculpted relief, an effect that engages the viewer in a visual paradox. This dialogue between paint and implied stone highlights Renoir’s late interest in the materiality of paint as a medium capable of evoking diverse textures—skin, foliage, and stone—while also pointing to his lifelong fascination with classical sculpture.

Psychological and Emotional Resonance

Although caryatids traditionally stand as impassive supports, Renoir’s figures exude warmth and subtle emotional presence. The left figure’s gentle gaze toward the viewer conveys openness and invitation, while the right figure’s sideward glance suggests private concentration. Their proximity and slight interlocking of limbs imply companionship and shared endeavor. The tension between their roles as architectural supports and as living beings imbues the painting with a reflective quality: viewers sense both the weight of tradition and the vitality of present moment. This emotional layering elevates Caryatids from a purely formal exercise to a meditation on femininity, artistry, and the interplay of duty and freedom.

Technical Analysis and Conservation

Caryatids is executed in oil on canvas mounted on board, chosen perhaps to provide a solid support for Renoir’s impasto. Technical imaging reveals an underdrawing in soft charcoal delineating the figures’ major contours and the niche’s architectural lines. Renoir applied a beige ground that warms the overall tonality and enhances flesh glow. Subsequent layers of pigment vary in thickness: the figures receive multiple glazes of flesh tones, while the garland and niche are blocked in more directly. Conservation efforts have removed discolored varnish that had muted the original brilliance of the greens and peaches; the painting’s surface remains remarkably stable despite Renoir’s heavy impasto in areas.

Reception and Critical Legacy

When exhibited in the years after its creation, Caryatids was admired for its technical polish and painterly grace, though some early critics found the subject matter overly decorative. Over the 20th century, however, art historians have recognized the painting as a critical synthesis of Renoir’s Impressionist innovation and classical inclinations. Caryatids has influenced subsequent generations of figure painters who seek to merge coloristic freedom with formal balance. Its unique dialogue between paint and architecture prefigures mid‑20th‑century explorations of materiality and illusion in figurative art, securing its place in the lineage of modernist appropriation of classical themes.

Conclusion

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Caryatids (Cariatides) deftly marries the painter’s late mastery of color, light, and brushwork with a profound engagement with classical form and symbolism. The two nude figures—bearing an implied architectural burden—become living embodiments of strength, grace, and the joyous possibilities of painterly expression. Through harmonious composition, nuanced chromatic interplay, and tender psychological insight, Renoir transforms an age‑old motif into a radiant testament to the enduring power of the human body as both structure and spirit. In Caryatids, Renoir offers a vision of art as the ultimate support—uplifting tradition through the warmth of living color.