Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

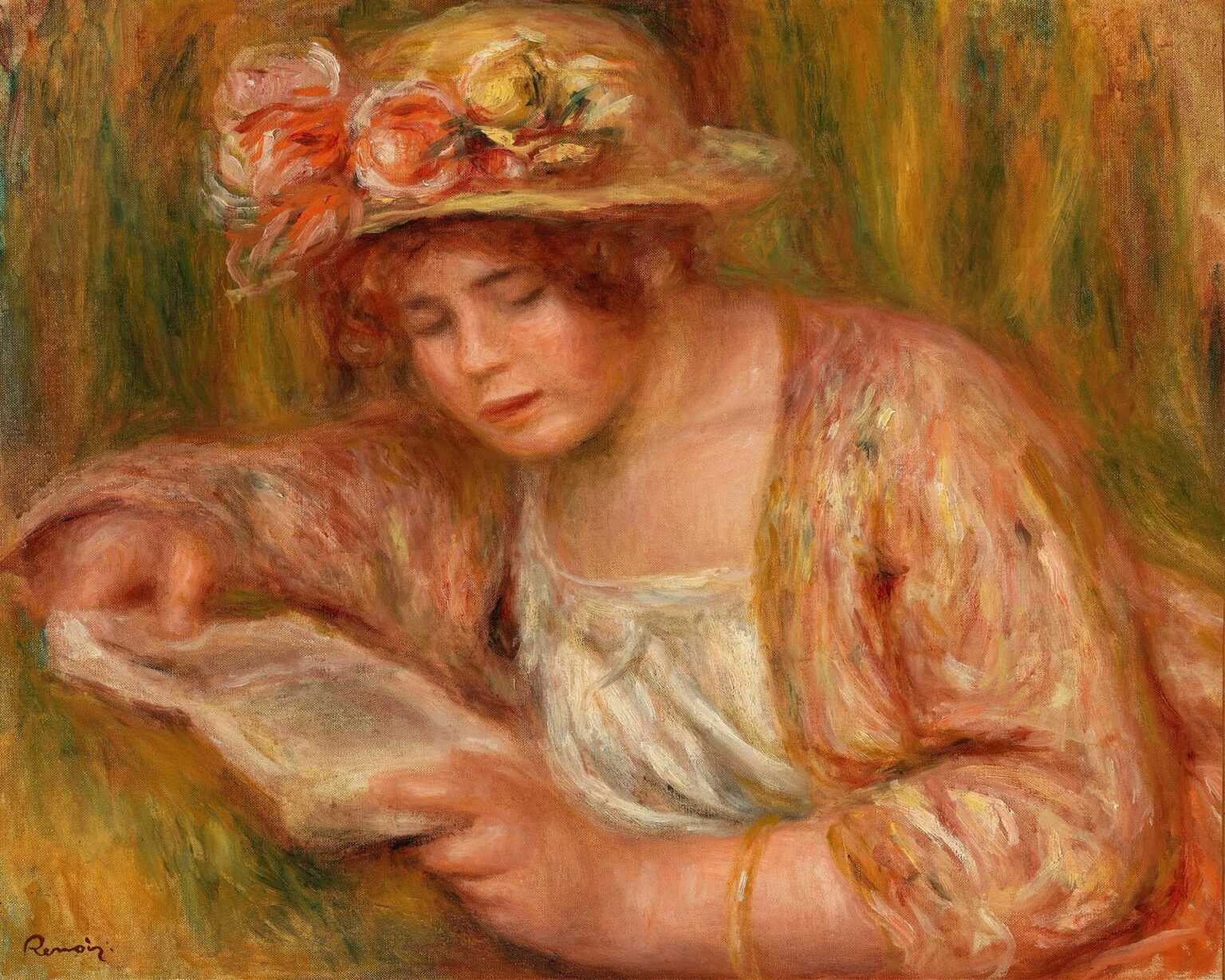

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Andrée in a Hat, Reading (Andrée en chapeau, lisant), painted in 1918, offers a tender glimpse into the artist’s late portraits, where luminous brushwork and intimate subject matter converge. At a time when Europe was emerging from the devastation of World War I, Renoir turned increasingly to scenes of quiet contemplation and personal solace. In this painting, the model Andrée is captured in a moment of private engagement with a book, her straw hat adorned with ribbons blending harmoniously with the surrounding palette. Through a careful orchestration of color, composition, and gesture, Renoir transforms a simple act of reading into a meditation on serenity, beauty, and the restorative power of art.

Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Late Style

By 1918, Renoir had moved decisively beyond the broken color and spontaneous brushwork of his early Impressionist experiments. Influenced by his admiration for Renaissance masters and by his recurrent struggles with rheumatoid arthritis, he adopted a more classical approach to form and structure. His late style—often called his “Ingres period”—favors smooth transitions of light and rich, warm flesh tones. Yet Renoir never abandoned his Impressionist roots: soft, vibrant hues and fluid brushstrokes continue to suffuse his canvases with life. Andrée in a Hat, Reading exemplifies this synthesis of classical modeling and luminous color, revealing the artist’s lifelong commitment to celebrating the human figure.

Historical Context of 1918

The year 1918 witnessed both the end of unprecedented global conflict and the beginning of a fragile peace. In Paris, artists and citizens alike sought comfort in everyday pleasures: laughter in cafés, strolls along the Seine, and moments of quiet reflection. Renoir—then in his late seventies—found solace in painting portraits of family, friends, and favored models. His choice to depict Andrée in an unguarded, studious pose reflects a broader societal yearning for intellectual reassurance and emotional respite. The book she holds becomes a symbol of continuity and hope, a reminder that culture and knowledge endure even amid the world’s upheavals.

Subject and Composition

At first glance, Andrée in a Hat, Reading presents a deceptively simple composition: a half-length figure against a loosely abstracted background. Andrée’s head tilts downward, her eyes focused on the open book cradled in her hands. The artist positions her centrally but offset slightly to the right, allowing the flowing lines of her straw hat and the drape of her garment to balance the frame. The diagonal of her bent arm creates a gentle rhythm that leads the viewer’s eye from her face to the page. By compressing space and minimizing extraneous detail, Renoir invites an intimate encounter with both subject and scene.

Andrée: Identity and Portrayal

While Renoir painted numerous portraits throughout his career, he rarely provided extensive documentation of his models. In this case, Andrée remains a figure of affectionate mystery—perhaps a younger friend, relative, or studio assistant. Renoir’s treatment of her facial features conveys youthful serenity: softly defined cheeks, slightly parted lips, and a relaxed brow suggest absorption in her reading. Her reddish hair, framed by the hat, echoes the warm tones applied throughout, creating visual unity. Though anonymous to history, Andrée embodies the enduring human impulse toward learning and reflection, qualities Renoir evidently admired.

The Role of Reading in Postwar Paris

Reading, as an activity, gained renewed significance in the aftermath of war. Literature and poetry offered solace, intellectual engagement, and escape from the trauma of battle. By portraying Andrée absorbed in her book, Renoir gestures toward this cultural revival. The book’s pages remain indistinct, allowing viewers to project their own literary associations onto the scene—perhaps a novel by Balzac, a volume of comforting verse, or a philosophical treatise. In this way, the painting transcends individual portraiture to become an emblem of collective yearning for knowledge and emotional healing.

Composition and Spatial Arrangement

Renoir constructs the painting’s spatial logic through a subtle interplay of foreground and background. The softly rendered backdrop—composed of vertical strokes in greens, ochres, and russets—suggests foliage or an interior tapestry, yet remains sufficiently abstract to avoid competing with the figure. Andrée’s torso occupies the midground, her garment’s folds defined by delicate modulations of light. The book she holds bridges these zones, its pale pages linking her form to the textured recess behind. By compressing spatial depth, Renoir fosters an intimate atmosphere in which viewer and model share a moment of quiet engagement.

Color Palette and Tonal Harmony

A hallmark of Renoir’s late work is his warm, resonant palette. In Andrée in a Hat, Reading, golden ochres and soft greens dominate the background, echoing the muted beige of the straw hat. Andrée’s rosy complexion and auburn hair stand out as focal points, while her dress—rendered in creamy whites and pale pastels—carries subtle echoes of background hues. The overall effect is one of chromatic cohesion, where no single color dominates but all contribute to a sense of luminous balance. Renoir’s mastery of tonal harmony imbues the work with both warmth and grace.

Brushwork and Painterly Technique

Although smoother than his youthful canvases, Renoir’s brushwork here retains the fluid vitality of Impressionism. The hat’s straw fibers are suggested by looping, feathery strokes, while the background foliage emerges from vertical dashes that mingle pigment directly on the canvas. Andrée’s skin is modeled through layered glazes, producing a gentle glow. In areas such as the book’s pages, Renoir uses broader, flat strokes to convey planar surfaces. The juxtaposition of varying textures—soft flesh, crisp paper, mottled backdrop—demonstrates the artist’s continued fascination with paint’s expressive possibilities and his ability to adapt technique to serve both form and feeling.

Treatment of Light and Atmosphere

Renoir captures an ambient, diffused light that seems to emanate from no single source. Instead, the illumination bathes Andrée evenly, softening shadows and accentuating the roundness of her features. Highlights on her book and the rim of her hat catch the eye, guiding attention to key elements of the narrative. The lack of harsh contrasts reinforces the painting’s serenity, evoking a late afternoon or overcast day where gentle luminosity envelops subject and space. Through this nuanced handling of light, Renoir emphasizes the painting’s contemplative mood and the inherent beauty of everyday moments.

The Open Book as Narrative Device

The book in Andrée’s hands functions as more than a prop; it is a narrative hinge. Unidentified yet universally recognizable, the volume invites viewers to imagine its contents—romance, philosophy, or poetic reflection. The way Andrée’s fingers cradle the spine suggests care and intimacy with the text. By leaving the pages blank of specific detail, Renoir preserves the painting’s openness, allowing each viewer’s imagination to fill the blank spaces with personal associations. In so doing, he underscores art’s capacity to spark countless private narratives from a single, simple gesture.

Depiction of the Female Gaze

Unlike many traditional portraits where the sitter engages the viewer directly, Andrée’s gaze is turned inward. This inward focus disrupts conventional dynamics, positioning the audience as silent observers of a private reverie. The female gaze, here directed toward the text she reads rather than the painter or viewer, asserts autonomy and intellectual agency. Renoir’s respectful portrayal—absent of objectifying or erotic overtones—reflects his belief in the dignity of his subjects. Andrée is neither demure nor posed; she is fully absorbed, her reading literally and figuratively at the center of her world.

Costume and Accessory Symbolism

Andrée’s straw hat, adorned with pastel ribbons, is more than a fashionable accessory; it signifies leisure and intellectual refinement. In early 20th‑century France, hats were markers of social identity and personal style. By painting the hat with as much care as the face, Renoir highlights its symbolic weight. The choice of straw—a natural, breathable material—echoes the organic tones of the background and suggests a spring or summer setting. The hat’s gentle shadow over Andrée’s features softens her expression, reinforcing the painting’s overall sense of harmony and calm.

Emotional Resonance and Intimacy

At its core, Andrée in a Hat, Reading is an exploration of intimate emotion. The painting conveys a sense of calm concentration, a momentary pause in the flow of daily life. Viewers may sense Andrée’s quiet joy, her curiosity, or her brief escape into the world of letters. Renoir’s tender rendering of her features—his subtle blending of blush tones and his evocation of soft hair strands—creates a palpable warmth. This emotional resonance transcends the particulars of time and place, inviting anyone who has ever been lost in a book to identify with her tranquil absorption.

Abstraction and Form

While representational in subject, the painting flirts with abstraction in its backdrop. Renoir’s vertical strokes and mottled color fields hint at impressionistic gestures, dissolving the boundary between figure and environment. Andrée’s form, rendered with greater solidity, anchors the composition. The tension between defined anatomy and suggestive ground mirrors the tension between conscious focus and unconscious ambiance in acts of reading. This dialectic enriches the painting’s formal complexity and aligns it with broader modernist explorations of partial abstraction.

Interaction with Surroundings

Though the background remains non‑descriptive, its tonal echoes of Andrée’s hat and dress forge a symbiotic relationship between sitter and space. The vertical rhythms of the backdrop resemble stalks or curtains, providing a gentle sense of enclosure. This enclosure feels protective rather than confining, as if Renoir crafted an idealized realm for introspection. The painting thus becomes less a record of a specific locale and more a distilled portrait of emotional space—one where thought and image merge in a unified, painterly vision.

Interpretation and Meaning

Interpretations of Andrée in a Hat, Reading may vary: some may see it as a celebration of feminine intellect, others as an elegiac response to postwar anxieties. The painting’s serene focus on reading can be read as a quiet manifesto for art’s power to heal and sustain. Andrée’s absorbed posture suggests that knowledge and imagination provide refuge from external turmoil. Renoir’s loyal adherence to beauty and human warmth—despite his own physical suffering—imbues the work with spiritual resonance. It stands as a testament to the enduring bond between artist, sitter, and viewer, united in a shared moment of contemplation.

Critical Reception and Provenance

When first exhibited, Andrée in a Hat, Reading received praise for its tender intimacy and refined technique. Critics noted Renoir’s skillful balance of classical form and Impressionist light, while some questioned whether his late style sacrificed vigor for smoothness. Over time, the painting found its way into prominent collections, admired for encapsulating Renoir’s mature vision. Contemporary scholars highlight its place within the artist’s evolution and its subtle engagement with early 20th‑century themes of leisure, gender, and intellectual renewal.

Legacy and Influence

Andrée in a Hat, Reading influenced subsequent generations of portrait painters drawn to scenes of quiet interiority. Its gentle pacing and harmonious palette can be seen echoed in later works exploring subjects in reflective states—whether reading, writing, or gazing inward. The painting’s synthesis of representational clarity and abstract suggestion foreshadows mid‑century experiments in portraiture, where emphasis on emotional atmosphere became paramount. Renoir’s model of integrating personal solace with aesthetic beauty remains a guiding touchstone for artists seeking to merge content and form.

Conclusion

In Andrée in a Hat, Reading (Andrée en chapeau, lisant), Pierre‑Auguste Renoir achieves a sublime union of gentle brushwork, rich color, and emotional depth. Painted in 1918 amid Europe’s fragile peace, the work captures a young woman’s private immersion in literature, transforming a commonplace activity into a timeless meditation on art, intellect, and human connection. Through compositional harmony and painterly mastery, Renoir invites viewers to share Andrée’s moment of serene focus, reminding us of the enduring power of beauty and the quiet joys of contemplation.