Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

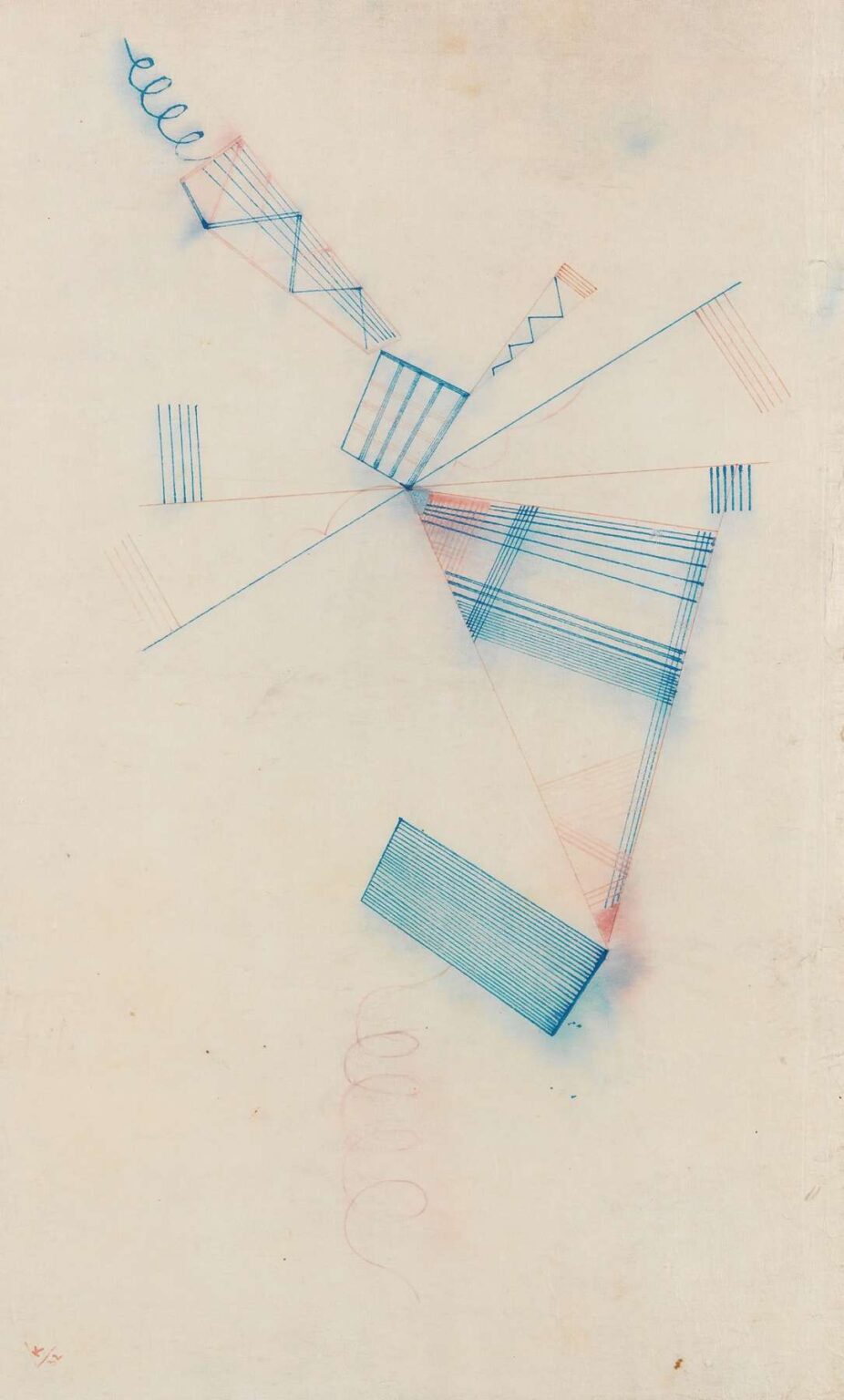

Wassily Kandinsky’s Two Spirals (1932) stands as a luminous testament to the artist’s lifelong pursuit of spiritual resonance through abstract form. Executed at the tail end of his tenure at the Bauhaus in Dessau, this composition distills decades of theoretical exploration into a deceptively simple arrangement of lines, planes, and curves. At first glance, the work appears minimalist—a pale, almost ethereal field punctuated by two vibrant coil-like motifs flanked by geometric fragments. Yet beneath this apparent economy of means lies a sophisticated interplay of color, movement, and symbolism. Kandinsky envisioned painting as an instrument of inner resonance, capable of summoning emotional and spiritual vibrations in the viewer. In Two Spirals, the artist channels this conviction into a visual concerto of dynamic tension and harmonic balance. Though the painting occupies only a fraction of the space of some of his grander canvases, it encapsulates with crystalline clarity the principles that governed his mature abstract practice: the power of the line, the soul of color, and the unity of form and spirit.

Historical Context

By 1932, Kandinsky had already traversed an extraordinary arc, from his early representational landscapes to the radical abstraction of the Der Blaue Reiter group and, later, the pedagogical rigor of Bauhaus instruction. The shifting political climate in Germany would force the closure of the Bauhaus that very year, rendering Two Spirals one of Kandinsky’s final statements within that influential milieu. At the Bauhaus, he coalesced his theoretical writings—most notably Concerning the Spiritual in Art and Point and Line to Plane—into a curriculum that married rigorous formal analysis with metaphysical inquiry. These texts posited that geometric elements such as points, lines, and angles carried intrinsic emotional and spiritual resonances. As Nazis targeted modernist tendencies as “degenerate,” Kandinsky’s work assumed a quietly defiant stance: a celebration of inner freedom and universal connectivity. In this climate of uncertainty, Two Spirals emerges as both a summary of his formal discoveries and a beacon of transcendence, offering an abstract vision unbound by the turmoil enveloping Europe.

Kandinsky’s Evolving Style

Kandinsky’s stylistic journey is characterized by a progressive distancing from the tangible world, initiated by his landmark 1911 exposé on the spiritual value of color and form. Early in his career, swirling organic shapes and vivid palettes suggested emotive landscapes; by the mid‑1920s, he had refined his iconography into crystalline geometries, often prefiguring the languages of Constructivism and De Stijl. Two Spirals crystallizes this evolution: the sweeping curves evoke earlier organic fluidity, while the crisp linear facets and planar blocks reflect his later Bauhaus pedagogical rigor. The spirals themselves occupy a liminal zone between organic and geometric, neither wholly biomorphic nor purely mechanical. This tension underscores Kandinsky’s ambition to fuse sensuous intuition with intellectual clarity. In balancing these impulses, he forged a unique abstract idiom—one in which each compositional choice resonates with both formal precision and metaphysical ambition.

Formal Analysis

Measuring modestly against the expanses of some late‑career works, Two Spirals nevertheless commands attention through its strategic use of negative space. The background—a pale, almost parchment‑like wash—serves as a neutral field, heightening the vibrancy of cobalt blue and cadmium red. Two tightly coiled spirals anchor the composition, positioned at opposing quadrants. These spirals, rendered with near‑mechanical precision, belie the intimate gesture of the hand. Radiating from their centers are slender, diagonal bands and clusters of parallel lines, which recede into ephemeral vanishing points. The deliberate asymmetry of these elements prevents stagnation: one spiral tilts gently, its adjacent grid‑like structure forming a subtle triangular counterweight, while the other anchors more groundward, its supporting geometry suggesting a skewed trapezoidal plane. The resulting interplay of curves and straight edges produces a visual oscillation, as the eye is invited to trace the spirals’ coils before jumping along the angular appendages.

Interpretation of Spirals

The spiral motif occupies a storied place in Kandinsky’s iconographic lexicon. For him, the spiral symbolized the unending expansion of the human spirit and the cyclical dynamics of cosmic forces. In Two Spirals, the duality implied by two interlocking coils suggests a conversation between complementary energies—perhaps masculine and feminine, physical and metaphysical, or inner intuition and outer structure. The spirals’ mirrored orientations create a silent dialogue across the canvas: one spirals inward, hinting at introspective withdrawal, while the other unfurls outward, signifying radiance and outward expression. This dialectic encapsulates Kandinsky’s belief in art as a site of transformation, wherein the viewer is invited to engage with opposing forces in harmonious synthesis. The choice to isolate and elevate spirals—rather than subsume them within a dense network of forms—underscores their symbolic primacy.

Use of Color

Color in Kandinsky’s late work was never arbitrary; it functioned as a kind of musical timbre, capable of evoking specific emotional frequencies. In Two Spirals, the dominant cobalt blue coils convey a sense of serenity, intellectual depth, and spiritual aspiration. Complementing this, subtle touches of cadmium red at the spirals’ cores introduce warmth, urgency, and corporeal vitality. These red accents pulse like the heartbeat of the composition, arresting the gaze and injecting dynamic warmth into the cooler blue registers. Thin diagonal lines in a muted ochre perch at strategic angles, offering neutral counterpoints that stabilize the chromatic tension. The restrained palette reinforces the painting’s meditative quality: rather than overwhelm with a riot of hues, Kandinsky achieves maximum expressive resonance through deliberate contrasts and harmonic juxtapositions. The result is an abstract symphony in two voices—one cool, one warm—that speaks directly to the viewer’s sensory intuition.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Two Spirals leverages asymmetrical balance to orchestrate a sense of measured equilibrium. The spirals’ offset placement prevents the composition from devolving into static symmetry; instead, they occupy dynamic fulcrums that keep the eye in motion. The interspersed grids and trapezoidal clusters act as visual weights, anchoring the spirals and offering directional cues. These geometric appendages extend beyond the coils, slicing into the negative space with angular precision. Such penetration into the surrounding field activates the void, transforming empty areas into zones of latent energy. The tension between filled and empty space underscores Kandinsky’s conviction that absence can be as potent as presence. Viewers find themselves drawn into a spatial dance, oscillating between the spirals’ centripetal pull and the outward thrust of the diagonal beams. This choreography of form crafts a three‑dimensional suggestion on an otherwise flat plane, engaging perceptual depth without resorting to traditional perspectival tricks.

Line and Movement

Line assumes a dual role in Two Spirals: it is both the constituent element of form and the conveyor of rhythm. Fine parallel lines form compact bands that extend from the spirals like staccato musical phrases. Their near‑equidistant spacing establishes a pulsating rhythm, evoking the cadence of sound waves or musical notation. Thicker strokes define the coils themselves, guiding the viewer’s gaze along looping pathways that never quite close—thus implying both closure and continuity. Where lines converge, they generate points of heightened tension, as though the painting were poised on the cusp of sonic resonance. Despite the crispness of these strokes, one senses the artist’s hand in the slight variation of pressure and the faint blur at certain intersections. This blend of precision and tactility animates the work, uniting the mechanical and the organic in a single, flowing gesture.

Symbolic and Spiritual Dimensions

For Kandinsky, abstraction was above all a pathway to inner revelation. He believed that shapes and colors could bypass the rational mind and speak directly to the soul. The spiral, in his symbolic vocabulary, represented evolution, growth, and the ceaseless unfolding of cosmic law. By isolating two such spirals, Kandinsky creates a microcosm of universal processes: birth and death, contraction and expansion, the interplay of cosmic opposites. The geometric appendages may be read as the structural frameworks of the material world, while the spirals themselves gesture toward the ineffable realms beyond. In the context of 1932’s social and political upheaval, this painting offers a sanctuary of inner harmony—a reminder that beneath surface chaos lies an immutable spiritual order. In this sense, Two Spirals is not merely a visual experiment but a meditative device, encouraging viewers to attune themselves to higher frequencies of being.

Viewer Engagement and Emotional Impact

Encountering Two Spirals, the viewer is compelled into active participation. One does not merely observe but completes the work through psychological projection and emotional response. The coils beckon inward contemplation, while the angular lines suggest outward expansion, prompting a rhythmic oscillation of attention and feeling. Some may sense a tranquil calm as blue hues dominate, while others experience the subtle shock of red punctuations. Regardless of individual interpretation, the painting’s clarity of structure and purity of form create a space for introspection. In the absence of literal imagery, the viewer is free to inhabit the formal relationships on their own terms, bringing personal associations to bear upon the abstract interplay. This openness is central to Kandinsky’s vision: true abstraction serves as a mirror to the viewer’s inner landscape.

Legacy and Influence

Though modest in scale, Two Spirals has exerted an outsized influence on the trajectory of modern abstraction. Its distilled vocabulary echoes through the work of post‑war abstract expressionists, minimalists, and geometric painters alike. Artists such as Ellsworth Kelly and Agnes Martin would take up similar dialogues of line, color, and space, pursuing in their own ways the marriage of formal purity and spiritual aspiration. Moreover, Kandinsky’s theoretical writings—embodied here in pictorial form—continued to inform generations of art educators and practitioners. The painting’s seamless fusion of analytical rigor and metaphysical depth exemplifies the Bauhaus ideal of art as a total experience. Today, Two Spirals remains a touchstone for anyone seeking to understand how abstract form can carry profound emotional and spiritual weight.

Conclusion

Two Spirals by Wassily Kandinsky transcends its spare appearance to reveal a universe of dynamic tensions and harmonious resonances. Through the careful calibration of line, color, and spatial arrangement, Kandinsky transforms the simple spiral into a cosmic symbol of duality and unity. Situated at a pivotal moment in modern art history, the painting distills years of theoretical inquiry into a luminous meditative field. Its enduring power lies in the invitation it extends to viewers: to enter into a rhythmic dialogue of form and spirit, to discover inner echoes within its abstract symphony, and to leave the canvas carrying the vibrations of a higher order. In this work, Kandinsky reaffirms his conviction that painting can serve as a gateway to the unseen, where geometry becomes prayer and color resonates like a note struck in the soul.