Image source: artvee.com

Artistic and Historical Context

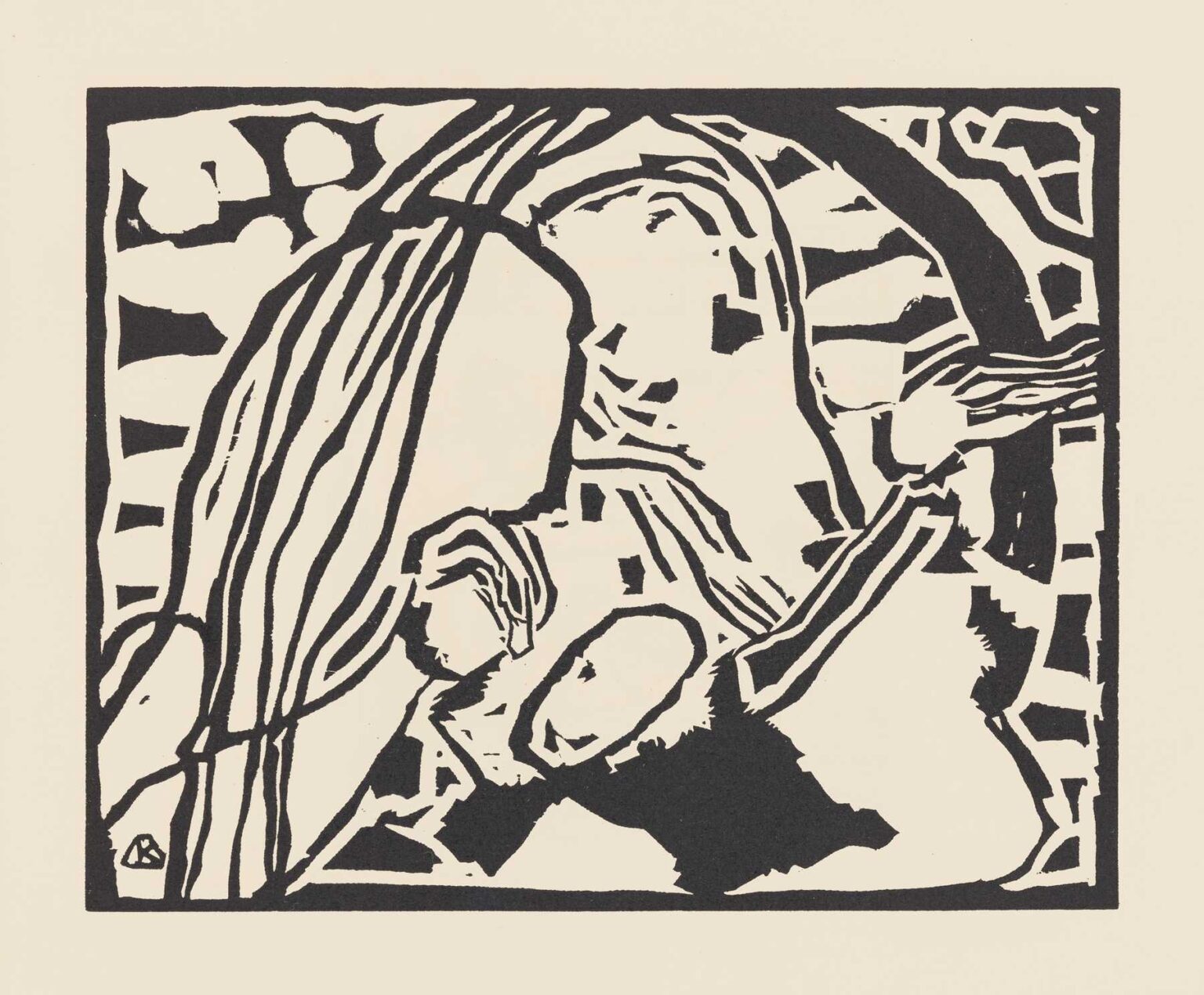

In 1913, the dawn of modern art was in full swing, and Wassily Kandinsky stood at its leading edge. His portfolio of painted works and theoretical writings had already begun to revolutionize how artists and viewers viewed abstraction. The same year saw Kandinsky publish Klänge (meaning “Sounds”), a groundbreaking portfolio of twenty woodcuts that translated his synesthetic theories into black-and-white graphic form. Where many of his previous paintings relied upon vibrant color, Klänge explores the power of line, shape, and contrast to evoke the rhythms and resonances of music. Plate 9 (Pl.09) occupies a key position within this series, exemplifying Kandinsky’s conviction that form and line alone can communicate emotional vibrations and spiritual echoes.

To appreciate Klänge Pl.09, one must consider Kandinsky’s philosophical journey. Beginning with his watershed essay On the Spiritual in Art (1911), he argued that colors and forms possessed intrinsic spiritual values, akin to musical tones. He likened painting to composition—colors became notes, and shapes became instruments. In his subsequent treatise Point and Line to Plane (1926), he systematized how points, lines, and planes could be orchestrated for maximum expressive effect. By 1913, Kandinsky had internalized these principles sufficiently to strip away color altogether. In Klänge, each woodcut becomes a silent symphony, its black-and-white riffs prompting viewers to “hear” line and shape as one hears melody and harmony.

Formal Composition and Visual Rhythm

At first glance, Klänge Pl.09 hinges on a vigorous interplay between thick, curving contours and thinner, more delicate linear elements. The woodcut’s rectangular border contains an active interior: sweeping arcs bend inward from the top and sides, their curves intersecting in a central vortex that suggests a gravitational pull. From this hub, feathery lines radiate like echoes, each tapering off into an irregular silhouette reminiscent of sound dissipating in space.

There is no single focal point; instead, the eye engages in a cyclical journey, following the path of bold curves, then tracing the finer lines that branch off like filigreed reverberations. The background, punctuated by irregular black patches and occasional small voids, feels alive with static interference, akin to white noise underlying a distant melody. Horizontal fragments of pattern near the bottom edge act as a bass line, grounding the composition and balancing the more prominent curves.

Kandinsky’s choice of woodcut as a medium confers a raw immediacy. The stark black ink pressed against the ivory paper amplifies contrast, lending each line razor‑sharp clarity. Yet the carving texture—visible in slight interruptions where wood grain intrudes—imbues the image with a live, organic pulse. This interplay of precision and imperfection mirrors musical performance, where crisp articulation coexists with the human breath that animates every note.

Musical Analogies and Synesthetic Echoes

For Kandinsky, abstraction was always a matter of translating auditory experience into visual terms. In Klänge Pl.09, the central swirling form might be heard as a sustained chord, its resonance giving rise to the subsidiary offshoots—staccato responses, trills, or harmonic overtones. The thicker arcs could correspond to lower registers, furnishing a sonorous foundation, while the proliferating thinner lines evoke rapid arpeggios or the fluttering vibrato of woodwinds.

This visualization of sound extends Kandinsky’s earlier practice of titling works with musical terminology—Improvisation, Composition, Rhythmus. While Klänge lacks overt color-based emotion, it compensates through dynamic tension between positive and negative space. The viewer “hears” the silent composition through the tension and release of forms: where dark shapes press in, white voids re-assert themselves, like a pause in music, creating anticipation for the next visual note.

If one were to translate Pl.09 into a musical score, it might take the form of a rendition for percussion and string ensemble—percussion delivering punctuated accents in the form of angular black marks, strings sustaining the curved forms with legato swells. The residual flecks of black around the edges could be imagined as echoes fading into silence.

Technical Mastery of Woodcut

Woodcut demands decisiveness: once a line is carved, there is no turning back. Kandinsky approached this medium with the same compositional rigor he applied to canvas but infused it with spontaneity. To achieve the sweeping curves, he would have wielded a broad gouge, carving deeply to ensure solid, unbroken prints. The finer striations—those thin, parallel lines—required delicate chisels and supple wrist action.

In print, these techniques manifest as areas of uniform blackity contrasted against slender white ribbons. The carved margins occasionally reveal the matrix’s grain, adding an uneven texture that further animates the surface. The slightly uneven ink distribution—where some lines appear more saturated than others—lends the final print a sense of immediacy, as though the energy of the carving burst forth in each impression. Kandinsky’s decision to leave these idiosyncrasies intact underscores his belief that every artistic gesture carries an echo of the artist’s spirit.

Symbolic and Spiritual Dimensions

Kandinsky viewed art as an instrument for spiritual renewal. In Klänge Pl.09, the swirling central form can be read as a portal or mandala—a metaphysical center through which the spiritual essence of sound passes into visual form. The surrounding lines might represent the radiating life force, the invisible currents connecting all things.

The black-and-white palette intensifies this symbolism. Black, often perceived as absence, here becomes the vessel for presence—a container for dynamic movement. White, typically associated with purity or silence, occupies spaces where potential awaits activation. The dialogue between these forces echoes Kandinsky’s theosophical leanings: the interplay of light and dark as reflections of the cosmic interplay of spirit and matter.

Moreover, Plate 9’s abstraction allows multiple levels of interpretation. One viewer might sense a dance of elemental forms—wind, wave, or flame—while another experiences a cosmic choreography of stars and void. This openness to subjective resonance exemplifies Kandinsky’s conviction that true abstraction transcends cultural or personal barriers, speaking directly to the universal heart.

Relation to Klänge Series and Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

Klänge occupies a singular place in Kandinsky’s body of work, bridging his early Expressionist experiments and his later Bauhaus period. Plates like Pl.09 demonstrate the artist’s willingness to revisit the emotive power of black-and-white after decades of chromatic inquiry. In comparison to earlier woodcuts by contemporaries such as Emil Nolde or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner—which often retained figural or landscape echoes—Kandinsky’s abstractions are uncompromisingly non-objective.

Within the Klänge series, Pl.09 distinguishes itself through its synthesis of organic and geometric—curvilinear forms share space with fragmented, quasi-architectural shards. This hybridization anticipates Kandinsky’s later return to more geometrically ordered compositions at the Bauhaus, where he embraced crystalline shapes in works like Composition VIII (1923). Yet Pl.09 retains a raw vitality that those later canvases sometimes smoothed over in the name of teaching clarity.

For scholars tracing Kandinsky’s evolution, Pl.09 serves as a pivotal moment: the final flowering of his pre‑war synesthetic experiments before the upheavals of World War I and his relocation to Weimar. Its daring abstraction helped pave the way for later avant‑garde movements—Russian Constructivism, De Stijl, and even Abstract Expressionism would draw upon Kandinsky’s ideas of non‑representational rhythm.

Legacy and Contemporary Resonance

Today, Klänge Pl.09 remains a touchstone for artists and theorists exploring the interplay of sound and vision. In the digital age, its stark forms have inspired generative art algorithms that translate audio frequencies into line-based patterns. Graphic designers cite Klänge as an early example of radical information design, where data (in Kandinsky’s case, musical theory) is rendered directly into visual form without intermediary representation.

In contemporary art education, Klänge Pl.09 often serves as a teaching tool for demonstrating how abstraction can convey emotional and spiritual content without color or recognizable imagery. Its appearance in exhibitions and publications underscores a renewed appreciation for black-and-white as a vibrant, expressive palette—rather than a mere reduction of color work.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl.09 (1913) stands as a masterful fusion of music, spirituality, and pure abstraction. Carved with bold decisiveness and printed with raw energy, it beckons viewers into a silent concerto of swirling lines, echoing forms, and vibrant contrasts. Its formal complexity, synesthetic resonance, and spiritual symbolism reveal Kandinsky at the height of his pre‑war creativity—fearless in stripping away color to lay bare the elemental language of art.

Over a century later, Pl.09 continues to inspire new dialogues across disciplines: from art history and music theory to digital media and mindfulness practice. Its haunting vitality reminds us that abstraction need not forsake feeling, and that even in monochrome, art can resonate with the deepest chords of the human spirit.