Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

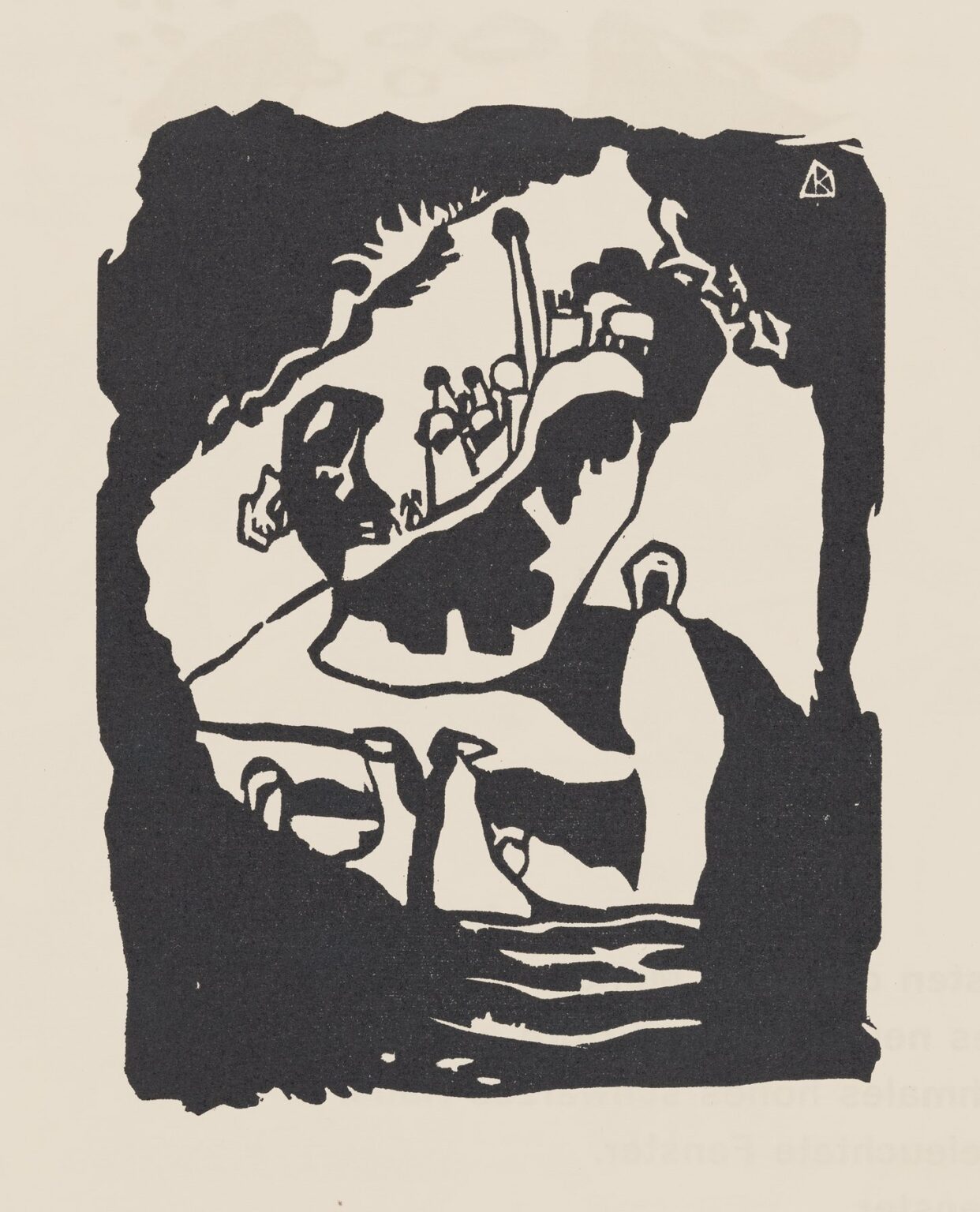

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 17 (1913) stands as one of the most enigmatic and compelling entries in his Klänge (“Sounds”) woodcut series. At first glance, the print appears as a tangle of black forms dancing across a creamy paper ground, but closer inspection reveals a meticulously crafted interplay of positive and negative space, rhythm and repose. Free from any overt representation, the work unfolds like a silent fugue: broad areas of inked relief frame irregular white channels, punctuated by delicate clusters of carved notches and sinuous lines. In this piece, Kandinsky distills his conviction that visual art can resonate with the spiritual and emotional potency of music. Through Klänge Pl. 17, he invites the viewer to listen with the eye and to feel the vibration of abstract forms as though they were cadences in an unseen composition.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1913, Kandinsky had firmly established himself as a leading light of the avant‑garde. After moving from Russia to Munich in 1896, he absorbed the currents of German Symbolism and Post‑Impressionism, but by the opening decade of the 20th century he had turned decisively toward abstraction. The founding of the Der Blaue Reiter group in 1911 gave formal shape to his belief in art’s spiritual mission, while the publication of Über das Geistige in der Kunst (“On the Spiritual in Art”) in 1912 provided a written manifesto for his theories of color and form. It was within this fertile atmosphere that Kandinsky embarked on the Klänge series, producing thirty woodcuts between 1911 and 1913. Though he continued to paint vibrant abstract canvases in parallel, the woodcuts offered a unique medium in which the stark contrast of black relief and white ground could sharpen his focus on compositional rhythm and spiritual resonance.

The Woodcut as Musical Metaphor

Kandinsky’s central ambition was to create a visual counterpart to music—a “sound” rendered in line and silhouette. He believed that painting and music shared a transcendent quality, capable of evoking emotions untethered from the material world. In the woodcut medium, he found an analogue to musical notation: carved relief shapes signified tones, uninked paper channels acted as rests, and the act of printing itself resembled the performance of a score. Klänge Pl. 17 epitomizes this philosophy. The border of black ink frames the composition much like a stave lines frame musical notes, while the white interior pathways twist and turn like melodic lines. Each stroke and notch seems to reverberate with unseen harmonies, urging the viewer to engage in a synesthetic experience of sight and imagined sound.

Formal Structure and Composition

At the heart of Klänge Pl. 17 is a roughly square layout dominated by a heavy, irregular black border. This border is not static; it breathes and flexes, its upper edge ragged and its lower edge tapering into a series of vertical slivers. Within this frame, a central swirling white area meanders from top to bottom, its edges scalloped by the surrounding black. This white channel functions as a river of silence, guiding the eye through the dense periphery. Along its course, small clusters of black relief—rounded dots, short staccato marks, and slender vertical lines—emerge like ripples or transient echoes.

To the left, an interior black mass rises like a cave mouth, its top edge adorned with tooth‑like protrusions that lend it a sense of guarded strength. To the right, a narrower white pathway opens onto a calmer pool, where a single elongated oval sits, reminiscent of a bell’s silent toll. Below, a horizontal band of white interrupted by short black strokes suggests gentle waves or the hushed suspension between two musical measures. Through these interlocking zones—cavernous, ribbon‑like, rippling—Kandinsky achieves a dynamic balance of tension and release.

Contrast, Rhythm, and Movement

The visual drama of Klänge Pl. 17 arises from the bold contrast between deep black relief and unblemished white ground. The broad inked areas assert gravity and weight, while the white interstices provide lightness and air. This dialectic creates a pulsing rhythm: heavy forms seem to advance, then recede into silence as the eye follows the white corridors. The repetition of certain motifs—pairs of dots, clusters of short lines, undulating curves—establishes a visual meter, akin to a recurring rhythmic theme in music. At the same time, subtle variations in the spacing, thickness, and orientation of marks prevent monotony, ensuring that each passage of the eye through the composition yields fresh tensions and harmonies.

Technical Mastery of Woodcut

Executing Klänge Pl. 17 required Kandinsky to harness the exacting demands of relief carving. The process begins with a full‑scale drawing, which is then transferred in reverse onto a wooden block. Using gouges and knives, Kandinsky carved away the areas meant to remain white, leaving the intended black forms in relief. Printing followed: the raised surfaces were inked and pressed onto paper, leaving a crisp, flat black image. Any stray nick or hesitation in carving would register starkly against the pale background. Yet Kandinsky’s cuts exhibit confidence and fluidity, with edges that range from smooth arcs to jagged breaks, lending the print both precision and spontaneity. The occasional flecks of uncarved wood grain visible in the black areas enrich the surface with subtle texture, a reminder of the handmade origin of these seemingly bold abstractions.

Spiritual and Symbolic Underpinnings

For Kandinsky, abstraction was a bridge to the spiritual realm. Influenced by Theosophy and Anthroposophy, he regarded geometric shapes and rhythmic patterns as carriers of universal energies. In Klänge Pl. 17, the sinuous white channel may symbolize a stream of spiritual insight carving its way through the subconscious, while the surrounding black forms represent the material or the unknown that the soul must navigate. The clusters of notches and dots can be read as spiritual sparks or moments of illumination. By avoiding any direct representation, Kandinsky ensures that the print functions as a meditation on the journey of the spirit—a visual hymn that listeners (or viewers) complete through personal contemplation.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Despite its abstraction, Klänge Pl. 17 has an immediate emotional impact. The interplay of enveloping black forms and winding white veins can provoke feelings ranging from introspection and calm to tension and exhilaration. Each viewer brings their own associations—memories of echoing caverns, flickering candlelight, or whispered melodies—to the experience. Kandinsky designed this openness of interpretation deliberately: abstraction, he believed, could evoke universal responses even as it resisted fixed meaning. In engaging with the print, one participates in a silent call‑and‑response, where the shapes speak and the viewer’s inner voice answers, forging a uniquely personal dialogue.

Place Within Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

While Kandinsky’s painted works of 1913—such as Composition VII—burst with color and layered brushstrokes, the Klänge woodcuts distilled his abstractions to their skeletal frameworks. Plate 17, positioned near the end of the series, demonstrates his command over the medium’s reductive challenges. The print’s success influenced Kandinsky’s later teaching at the Bauhaus, where he continued to emphasize the spiritual and musical potential of form and color. Yet never again did he so fully exploit the chiaroscuro of relief print to create an immersive, silent fugue. Klänge Pl. 17 thus occupies a singular niche: both a culmination of his early theories and a springboard to subsequent geometric and color explorations.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

The Klänge series has exerted lasting influence on graphic design, abstract painting, and multimedia art. Plate 17’s bold choreography of form and void has inspired poster artists and digital designers seeking to communicate emotional resonance through minimal means. Its spiritual underpinnings resonate in contemporary dialogues about art as a pathway to mindfulness and inner reflection. In a fast‑paced visual culture, Klänge Pl. 17 offers a model of sustained, contemplative engagement, reminding viewers of the power of silence, emptiness, and the subtle vibrations that lie beneath apparent stillness.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 17 (1913) remains a masterwork of abstract woodcut, a striking testament to the artist’s vision of visual art as silent music. Through its dynamic dance of black relief and white interstice, its confident carving and rhythmic intricacy, the print transcends representation to become an invitation: listen with the eye, feel the pulse of shape, and journey inward along the winding channels of form. Over a century later, its bold contrast and spiritual resonance continue to captivate, affirming Kandinsky’s legacy as a pioneer who taught the world to see—and to hear—the hidden harmonies of abstraction.