Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

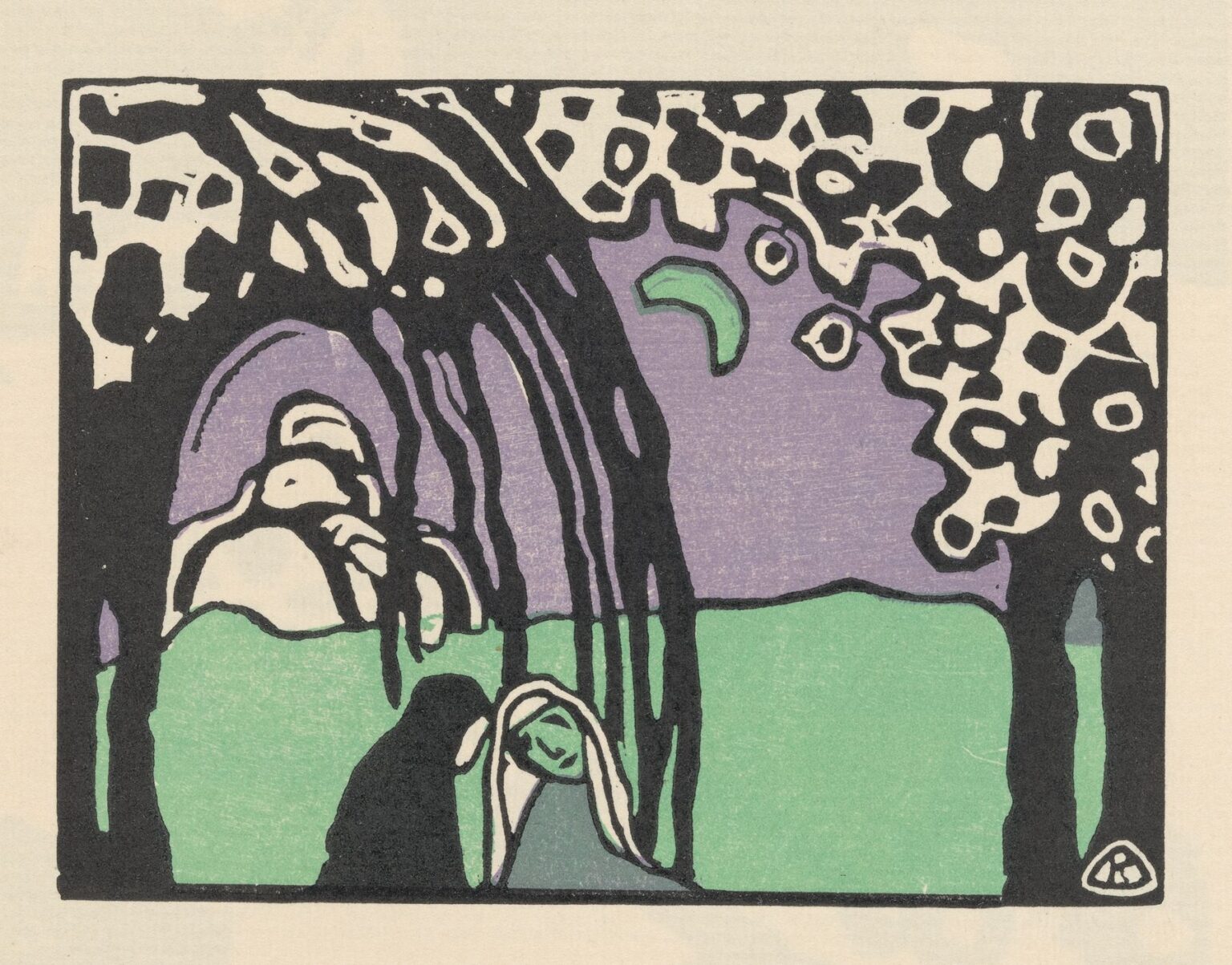

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 20 (1913) emerges as a luminous testament to the artist’s conviction that visual form could resonate like music and elevate the spirit. Executed late in the creation of his Klänge (“Sounds”) woodcut series, this plate stands apart through its daring introduction of color into a medium more often defined by stark black‑and‑white contrasts. Here, muted violet and pale green wash behind and across black relief, transforming the composition into an evocative interplay of silhouette, hue, and surface. No figure or landscape is depicted in the traditional sense; instead, we encounter abstract motifs that pulse with musicality and spiritual charge. From the slender vertical lines that drop like arpeggios through the center, to the circular patterning at the print’s upper right, every element suggests a note, a chord, or a rest. In Klänge Pl. 20, Kandinsky offers us not merely a print but a visual score, an invitation to “hear” color and shape as one would a symphony of inner necessity.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1913, Kandinsky had already become a towering presence in European modernism. His early explorations—rooted in realism and Symbolism—shifted decisively toward abstraction after the founding of the Der Blaue Reiter group in 1911. His landmark text On the Spiritual in Art (1912) outlined a philosophy wherein color and form were elevated to carriers of inner experience, capable of awakening in viewers the very emotions and states of mind that music could evoke. The Klänge woodcut series, initiated in 1911 and largely completed by mid‑1913, represented a parallel undertaking: to translate those spiritual and musical aspirations into the graphic medium of relief print. Whereas Kandinsky’s paintings employed lush color and layered brushwork, the woodcuts demanded an economy of means. Early plates of the series embraced black‑and‑white abstraction; Pl. 20 breaks that mold by introducing a limited, yet evocative, color palette. In so doing, Kandinsky signaled both a culmination of his experiments in the graphic idiom and a bridge toward the chromatic freedom of his later paintings.

Kandinsky’s Vision of Visual Music

At the core of Kandinsky’s artistic ambition lay the idea of synesthesia—the crossing of sensory thresholds wherein color could be heard and line could be felt. He believed that visual rhythms and musical rhythms shared a common spiritual origin. In Klänge Pl. 20, the vertical black striations that descend from the upper left suggest a series of rapid staccato notes, while the gentle green expanse at the bottom evokes the sustained hum of low strings. The lilac sky behind the arching black stems carries a sense of nocturnal mystery, reminiscent of a muted clarinet or cello timbre. Kandinsky often referred to his compositions as “improvisations,” underscoring the improvisatory logic behind their forms. Even in this print, which required the precision of carving in reverse relief, one senses an improvisational spirit—forms that respond to one another as instruments might in a spontaneous chamber performance.

Formal Composition

Klänge Pl. 20 is anchored by a large, abstracted arch on the left, which frames a cluster of vertical lines. This arch, rendered in heavy black relief, sweeps upward and then curves inward, its underside punctuated by delicate white strokes that suggest the tumble of shimmering overtones. At its base rests a rounded form that veils the emergence of the vertical lines, perhaps akin to a musical motif that repeats but is subtly altered each time. To the right, the dense pattern of circular and hexagonal shapes in black and white appears almost cellular, as though a curtain of sound is vibrating with microtonal variations. Beneath these shapes, a broad horizontal field of pale green asserts itself, its unbroken surface offering a calm counterbalance to the animated architecture above.

The composition unfolds in three registers: the solid black arches and rhythmic lines on the left; the playful patterning of circles and polygons in the upper right; and the tranquil green plateau below. Yet these zones are never isolated. Thin black tendrils extend from the arch into the circle cluster; wisps of white line cut through the green field; and the pale violet ground provides a visual bridge between upper and lower halves. Through this careful orchestration of form and space, Kandinsky creates a print that feels at once dynamic and harmonious.

The Introduction of Color

Unlike earlier Klänge plates—principally black relief printed on white paper—Plate 20 incorporates two muted inks alongside black. The artist chose a soft violet to fill the background and a tender mint green for the lower expanse. These colors, far from decorative afterthoughts, play an integral role in the print’s rhythm. The violet area feels introspective, almost echoing the sonorous depth of a viola or bassoon. The green suggests fresh energy or the calm rumble of a double bass. Together, they create a subtle bi‑tonal effect, allowing the black relief to function as a unifying element that ties the two registers into a cohesive whole. This was a bold technical move, requiring multiple passes through the press and precise registration to ensure that the black, violet, and green layers aligned perfectly. Kandinsky’s willingness to risk this complexity speaks to his desire to expand the expressive vocabulary of his woodcut series without relinquishing its disciplined abstraction.

Technical Execution

Producing Klänge Pl. 20 demanded exceptional command of the woodcut medium. Each black contour and interior cut was carved in reverse into a wooden block. The addition of color required separate linked blocks or a reduction technique to print violet and green fields first, followed by the final black overprint. Kandinsky likely inked the green block, printed the paper, cleaned the block, then inked the violet block and printed in a second pass, before finally applying the black ink block. Each pass risked slight misregistration, which could blur or misalign forms. Instead, the print emerges with crisp edges and smooth color films. The wood’s natural grain occasionally peeks through the solid color fields, imparting a subtle texture that recalls the human touch behind the mechanical process. In Klänge Pl. 20, technical mastery and creative daring converge, resulting in a work that vibrates with both precision and vital energy.

Symbolic and Spiritual Dimensions

Though entirely non‑representational, the forms in Plate 20 carry deep symbolic resonance. The arch on the left may be seen as a gateway—an invitation to cross from the material realm into a spiritual dimension. The vertical lines beneath it suggest channels or conduits through which inner necessity flows. The circular pattern on the right evokes cells or cosmic particles, hinting at the microcosm within the macrocosm. Kandinsky’s studies of Theosophy and Anthroposophy had taught him to regard geometry and proportion as spiritual signifiers. The triadic color scheme—black, violet, and green—may correspond to stages of spiritual transformation: black as the void or the seed, violet as introspection and psychic awakening, and green as renewal and harmony. In this sense, the print functions as a meditative diagram that guides the soul through symbolic stages of awakening.

Emotional Impact

When one stands before Klänge Pl. 20, the first impression is of tension and release. The starkness of the black relief carries weight and gravity, while the pastel hues offer a gentle calm. The viewer’s gaze is drawn upward by the rhythmic verticals, then sweeps across to the animated circles, and finally settles into the spacious green field—a kind of visual exhalation. This journey evokes emotional responses akin to listening to a musical composition that moves from a vigorous allegro through a playful scherzo to a serene adagio. Without prescribing any specific narrative, Kandinsky invites a purely experiential engagement: each observer may feel exhilaration, contemplation, or quiet wonder as the forms unfold in the imagination.

Relationship to Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

In his painted works of the same period—Composition VII (1913) and Improvisation 30 (1913)—Kandinsky explored kaleidoscopic color combinations and dense, overlapping forms. In contrast, the Klänge woodcuts demanded a distilled approach: here, Kandinsky tested how far abstraction could go when restricted to relief carving and limited color printing. Plate 20 occupies a unique place, merging the structural finesse of woodcut with the chromatic playfulness of his canvases. It foreshadows his later embrace of color fields at the Bauhaus and anticipates the more geometric aesthetics of the 1920s. Yet in its fusion of musical metaphor, spiritual inquiry, and printmaking prowess, Klänge Pl. 20 remains a singular achievement, representing both the culmination of a series and a gateway to new horizons in abstraction.

Legacy and Influence

The Klänge portfolio, and Plate 20 in particular, left an enduring imprint on modern art and design. By demonstrating how relief print could convey the fullness of Kandinsky’s synesthetic vision, these woodcuts inspired fellow avant‑garde artists to experiment with graphic media as a primary form of abstraction. The interplay of color and black relief anticipated mid‑20th‑century developments in serigraphy and graphic design, where bold shapes and minimal palettes became hallmarks of modernist aesthetics. Contemporary designers continue to draw on Plate 20’s balance of spontaneity and structure, its rhythmic patterns, and its mastery of surface. Moreover, Kandinsky’s belief in art as a spiritual practice has resonated ever since, encouraging viewers to approach abstraction not merely as decorative or academic, but as a means of touching deeper layers of human experience.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 20 stands as a masterwork that unites the precision of woodcut printmaking with the boundless imagination of visual music. Through its daring integration of pastel hues and stark black relief, the print transcends the confines of representation to become a symphonic tapestry of form and spirit. Each curve, line, and color field functions as a note or chord in a carefully composed visual score—one that continues to speak across time, inviting viewers to listen with the eyes and to discover the hidden harmonies of abstraction.