Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

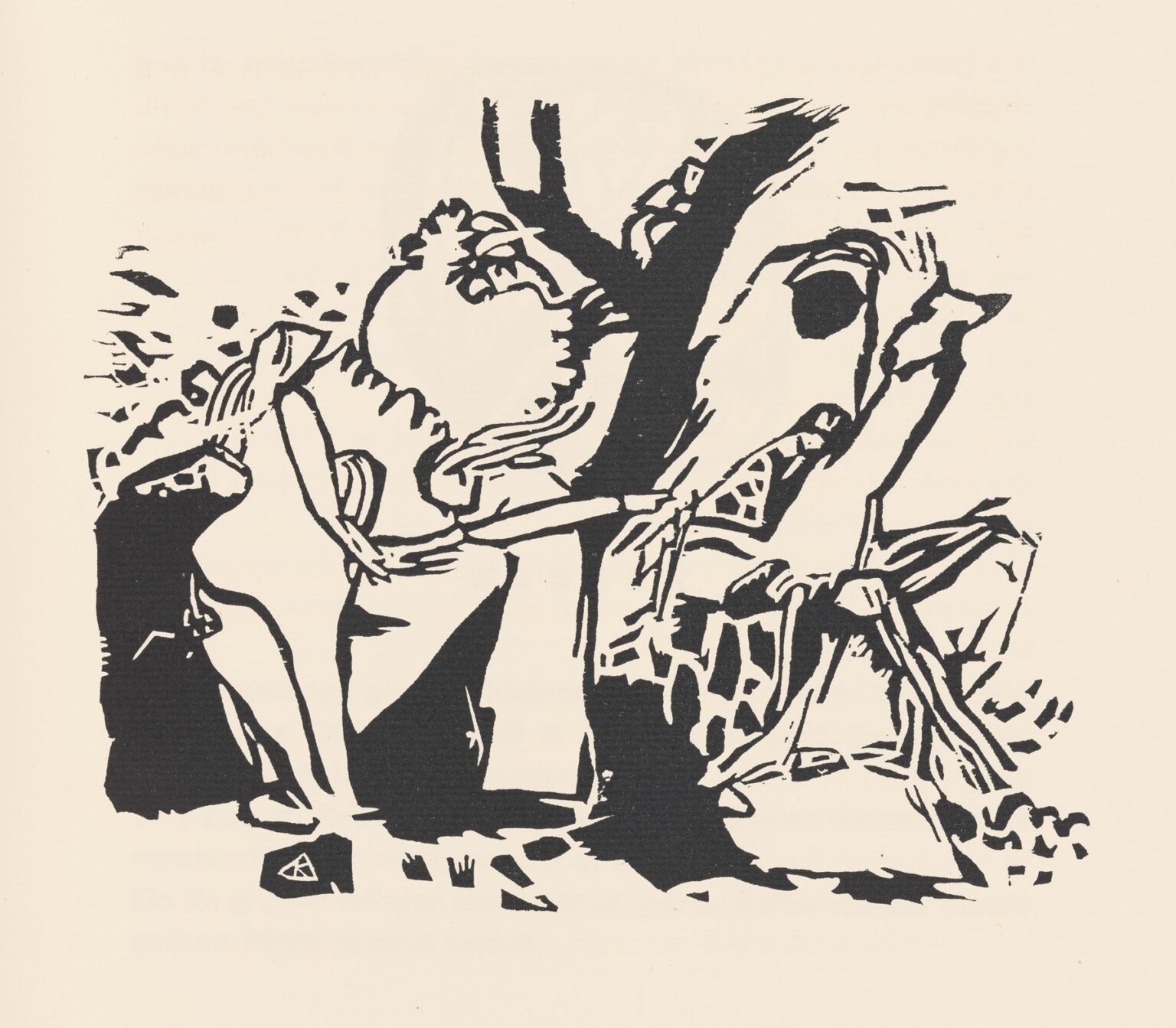

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 21 (1913) represents a pivotal moment in the artist’s radical exploration of abstraction and graphic experimentation. As the twenty‑first plate in his Klänge (“Sounds”) portfolio, this woodcut transcends the boundaries of representational imagery and invites the viewer into an experience that is at once visual, musical, and spiritual. The print unfolds as a dynamic interplay of black relief and white void, with sweeping curves, jagged diagonals, and delicate, calligraphic lines that pulse across the paper like notes in a fugue. Each encounter with the work reveals new resonances—forms that seem to sing, rhythms that feel like spoken incantations, silences that hum with potential energy. In this analysis, we will examine the cultural and theoretical context that gave rise to Klänge Pl. 21, unpack Kandinsky’s formal innovations, explore the woodcut’s technical execution, and consider the lasting emotional and intellectual impact of this remarkable print.

Historical and Cultural Context

By 1913, the currents of modern art had reached a fever pitch in Europe. Movements such as Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism were dismantling inherited conventions of perspective, form, and subject matter. Kandinsky, a Russian émigré who had made Munich his home, stood at the forefront of this avant‑garde. His early works were grounded in plein‑air observations and Symbolist influences, but after co‑founding the Der Blaue Reiter group in 1911, he devoted himself to the pursuit of pure abstraction. His 1912 treatise On the Spiritual in Art articulated a bold vision: color, line, and form themselves could transmit inner necessity—the deepest stirrings of the human spirit—without recourse to mimetic representation.

Printmaking offered Kandinsky a complementary avenue to canvases for disseminating his radical ideas. The woodcut, in particular, appealed to him for its reductive potential: it demanded a stark interplay of positive and negative, of shape and silence. The Klänge series, created between 1911 and 1913, took its name from the German word for “sounds,” underscoring Kandinsky’s conviction that visual art could mirror musical structure and evoke resonant frequencies within the viewer’s psyche. Plate 21 emerged in the series’ closing phase, when Kandinsky had refined his graphic vocabulary to a remarkable degree of structural and spiritual sophistication.

Kandinsky’s Theoretical Foundations

Central to Kandinsky’s practice was the notion of synesthesia—a blending of sensory modalities whereby color could evoke sound, and line could carry emotional timbre. He argued that sight and hearing shared common neurological pathways, making it possible for visual forms to possess the quality of musical notes or chords. In his writings, he frequently used musical metaphors: his paintings were “improvisations” or “compositions,” and he spoke of rhythms and counterpoints in the language of form. Klänge Pl. 21 embodies this synesthetic ambition, presenting a visual counterpoint to musical performance, with each black shape and white interval functioning like a tone or rest in a graphic score.

Kandinsky was also influenced by Theosophy and other spiritual movements that posited an invisible realm beneath the physical world. He believed that pure abstraction served as a portal to this higher dimension, allowing viewers to transcend the material plane and access universal truths. In Klänge Pl. 21, the forms—though wholly non‑representational—can be read as symbols of cosmic forces: the sinuous curves might represent currents of energy, the jagged strokes rising like spiritual sparks, and the expansive white fields serving as spaces for contemplation and inner absorption.

The Klänge Series and the Woodcut Medium

While Kandinsky’s painted abstractions dazzled with vibrant color and layered brushwork, his woodcut prints distilled his ideas to their structural essentials. The Klänge portfolio comprised thirty plates, each carved in relief onto wooden blocks. The process required the artist to imagine a composition backwards—removing material to leave only the intended image in relief. Black ink was applied to the remaining surfaces and then transferred to paper through mechanical pressure, producing prints in which every form and line was defined by its absence as much as its presence.

In the woodcut medium, Kandinsky found an opportunity to sharpen his focus on rhythm, contrast, and structural balance. Freed from the expressive possibilities of color, he turned to the stark black‑and‑white dialectic to convey maximum emotional intensity. Plate 21 demonstrates how he harnessed woodcut’s inherent constraints—its limited tonal range, its calligraphic precision, its textural grain—to forge a composition that resonates with formal rigor and spiritual depth.

Formal Analysis of Plate 21

At the heart of Klänge Pl. 21 lies a complex network of intersecting forms. A broad, undulating arc sweeps from the bottom left to the upper right, slicing through the composition like a musical phrase carried on a breath of wind. This curve divides the field into two contrasting zones: a denser cluster of shapes below and a more open expanse above. Within the lower zone, thick black masses interlock with slender white channels, creating a sense of subterranean movement—perhaps akin to the low throbbing of cellos or the rumble of bass. Scores of tiny, calligraphic strokes dance around these masses, forming rhythmic textures that recall tremolo or fluttering hi‑hats.

Above the central curve, the forms lighten and spread out. Thin, diagonal slashes fan across the white ground, suggesting staccato notes or whispered asides. A rounded, leaf‑like shape hovers near the top, its black silhouette offering a moment of lyrical repose. Yet the eye is inevitably drawn back to the tension of the lower half, where shapes clash and embrace, generating an almost palpable charge. Throughout, negative space is not a neutral void but an active participant—its irregular contours shape the black relief and create breathing room for the eye, much like rests punctuate a musical score.

Contrast, Rhythm, and Spatial Dynamics

The potency of Plate 21 stems from its dynamic contrasts. The black relief is inked heavily, asserting a commanding presence against the pale paper. Yet Kandinsky avoids monolithic darkness by carving narrow white slits and punctuations within these masses, allowing the print to vibrate with energy. Conversely, the white ground is animated by clusters of black fragments, preventing expanses of emptiness from feeling static or inert. This relentless tension between presence and absence fuels the composition’s rhythmic momentum—an abstract dance in which each form leads and then follows in an ever‑shifting dialogue.

Spatially, the print achieves depth without illusionistic perspective. Overlapping shapes imply forward and backward movements, while the interplay of thick and thin lines suggests proximity or distance. Yet no single vanishing point anchors the scene; instead, Plate 21 unfolds as a non‑hierarchical field where every mark matters equally. The viewer’s gaze glides across the surface, tracing a circuit that never settles, as though navigating a musical fugue that loops elegantly on itself.

Technical Execution and Material Presence

Creating Klänge Pl. 21 demanded a high degree of technical mastery. Carving a woodcut requires planning: the artist must anticipate how each cut will translate into printed form. Kandinsky’s lines are confident and economical, with no wasted marks. The wood grain occasionally appears in the black areas, lending the relief a natural, organic texture that contrasts with the geometric precision of certain strokes. Slight variations in ink distribution—areas where black pools more thickly or breaks away to reveal the paper beneath—imbue the print with life and a sense of the artist’s hand.

The physical presence of the print also contributes to its impact. The subtle indentation of the carved block into the paper surface creates a tactile relief, inviting close viewing and even gentle tracing of the forms. This materiality bridges the gap between artist and viewer, reminding us that Klänge Pl. 21 is not an illusion but a crafted object, born of labor and vision.

Emotional and Spiritual Resonance

Despite—or perhaps because of—its abstraction, Plate 21 strikes an immediate emotional chord. Viewers may experience a rush of excitement at the print’s rhythmic pulses, a moment of calm in the airy upper zone, or a burst of curiosity as shapes emerge and recede. Kandinsky intended such visceral responses, believing that abstraction could evoke universal feelings unmediated by narrative. The print’s dynamic interplay of form and silence echoes the structure of music, where sound and rest coalesce to shape emotional arcs.

On a deeper level, the plate operates as a spiritual map. Kandinsky’s adherence to Theosophical ideas infuses the work with metaphysical implications: the ascending arcs may represent the soul’s yearning for higher realms, the clustering shapes below could signify the complexity of earthly existence, and the small, intermittent marks scattered across the surface might symbolize sparks of divine inspiration. The print thus becomes a meditation, offering viewers a space to project their own inner landscapes and to experience abstraction as an act of contemplation.

Place Within Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

Klänge Pl. 21 occupies a special place in Kandinsky’s body of work, bridging the painterly experiments of his Improvisations and Compositions with the graphic intensity of his later Bauhaus period. While his oil paintings of the same era dazzled with color harmonies and layered brushwork, the Klänge prints distilled his ideas to their barest elements. Plate 21 exemplifies this distillation: every line, arc, and notch matters, and the absence of color directs undivided attention to rhythm, structure, and spiritual intent. The success of these prints influenced Kandinsky’s teaching at the Bauhaus and shaped future generations of abstract artists and designers who recognized the expressive power of black‑and‑white geometry.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Over a century since its creation, Klänge Pl. 21 continues to inspire artists, musicians, and scholars. Its emphasis on form as a vehicle for emotion resonates with contemporary explorations in graphic design, digital art, and multimedia installation. Musicians and choreographers have responded to Kandinsky’s notion of visual music by creating works that translate abstract forms into sound or movement. In academic circles, Plate 21 is studied as a cornerstone of synesthetic theory and as an exemplar of early modern abstraction that transcended representational art.

Furthermore, the print’s enduring appeal lies in its openness: without fixed meaning, it invites each viewer to embark on a personal journey through shape and silence. In an era saturated with images and information, Klänge Pl. 21 offers a space for focused attention and inner listening—a reminder that, sometimes, less truly is more.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 21 stands as a masterful fusion of musical analogy, spiritual aspiration, and technical virtuosity. Through the bold tension of black relief and white void, the print orchestrates a silent symphony of forms that engages viewers on visual, emotional, and contemplative levels. Emerging at the apex of Kandinsky’s pre‑war abstractions, Plate 21 exemplifies his belief in art’s capacity to express inner necessity and to forge a universal language of shape and rhythm. Over a century later, its dynamic composition and spiritual resonance continue to captivate, affirming Kandinsky’s legacy as a pioneer of abstraction and a visionary of visual music.