Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Biographical Context

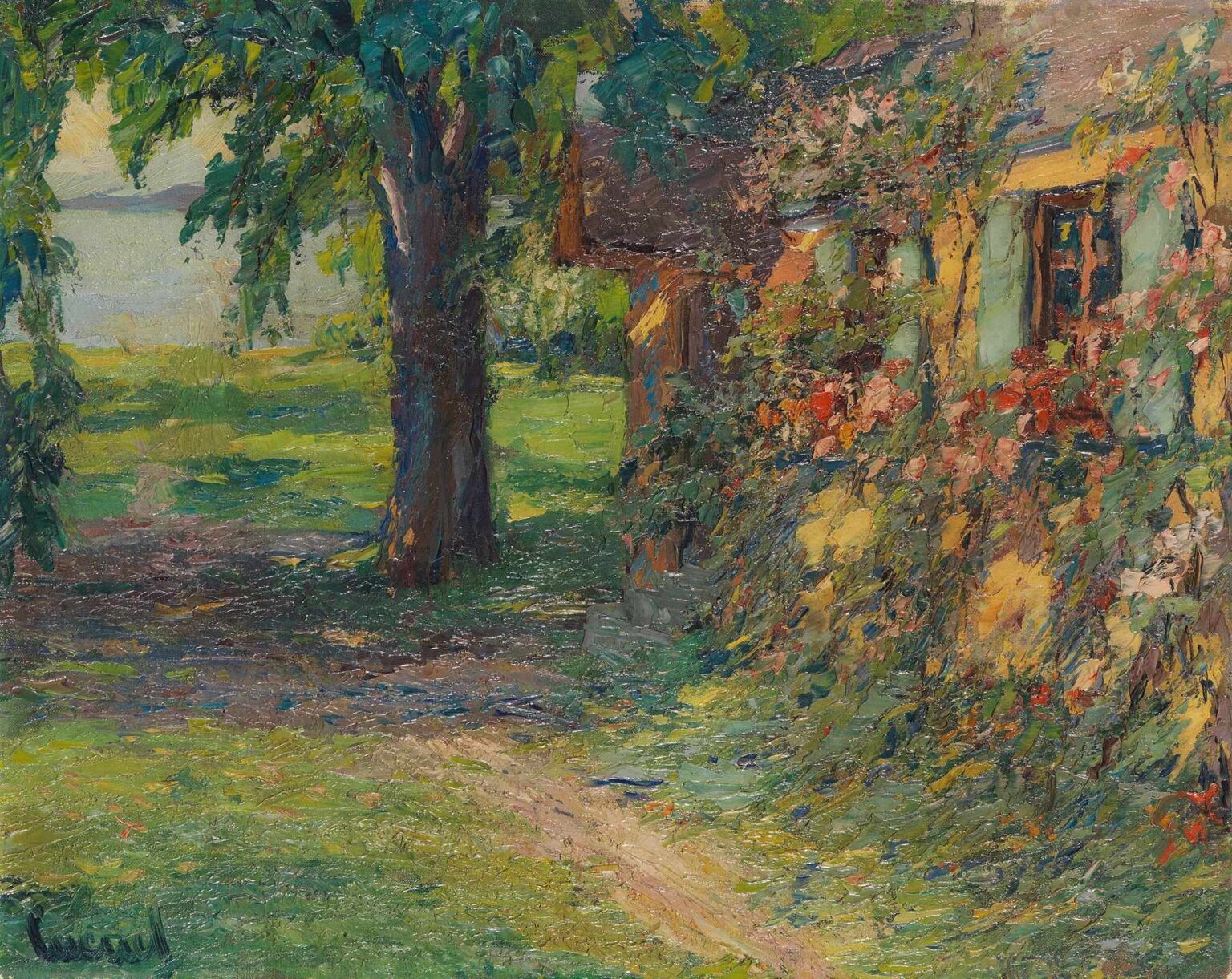

Edward Cucuel (1875–1954) was an American painter of German parentage who spent much of his career traversing the art centers of Europe and the United States. Born in San Francisco and raised in Stuttgart, he trained in Munich under the influence of the plein air tradition and later at the Art Students League in New York. By the 1910s, Cucuel had absorbed both the color sensibilities of the French Impressionists and the compositional rigor of the Barbizon painters. In the wake of World War I, he settled near Lake Starnberg, drawn by its pastoral tranquility and luminous atmosphere. “The Artist’s House on Lake Starnberg,” painted in 1920, reflects his mature synthesis of transatlantic influences and his lifelong fascination with the interplay of architecture and landscape.

Munich and the Plein-Air Tradition

Cucuel’s time in Munich exposed him to a generation of landscape painters who championed outdoor painting, following in the footsteps of the Barbizon school. He learned to capture fleeting light effects directly on canvas, often working from small studies made in situ. This approach encouraged a spontaneity of gesture and a vivid interplay of color. While Munich’s art academies maintained a conservative bent, Cucuel gravitated toward the more avant-garde circles of the Munich Secession, where he was encouraged to experiment with broken color and dynamic brushwork. The scenography of Lake Starnberg, with its shifting light and gentle topography, offered an ideal laboratory for advancing his plein air practice.

Post-War Cultural Climate

The immediate postwar years in Germany were marked by social upheaval and economic hardship, yet also by a collective longing for renewal and peaceful reflection. Artists like Cucuel sought refuge from the scars of conflict in the restorative power of nature. His choice of subject—an intimate view of his own dwelling, framed by verdant foliage and the serene waters of Starnberg—can be read as an assertion of personal stability and artistic autonomy. In 1920, as the Weimar Republic took shape, this painting emerged as a quiet manifesto of hope: a vision of domestic harmony grounded in an environment that appeared both timeless and resilient.

Subject Matter: The Artist’s House

Rather than an imposing estate, Cucuel’s house is modest in scale and rustic in character. Its ochre-toned walls, simple shuttered windows, and gently sloping roof suggest a vernacular building rooted in Bavarian tradition. Climbing roses and ivy cascade over one façade, softening its geometry and signaling a long-standing coexistence with the surrounding flora. The open window hints at domestic life, yet no figures appear, allowing the structure itself to become a silent protagonist. By depicting his own residence, Cucuel invites the viewer into a personal realm—his studio and sanctuary—where art and everyday existence merge seamlessly.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

At first glance, the painting adheres loosely to the rule of thirds: the house occupies the right vertical third, while a large tree anchors the center. Yet Cucuel avoids static symmetry by placing the tree slightly off-center and by introducing a curving path that weaves diagonally across the foreground. This pathway draws the eye into the composition, creating a sense of journey and discovery. The horizontal band of the lake and distant hills forms a low horizon line, compressing the spatial depth and emphasizing the vertical interplay of tree and architecture. Through these compositional choices, Cucuel balances stability with movement, guiding the spectator through an immersive landscape.

Light and Color Harmony

Cucuel’s palette celebrates the vibrancy of a late summer morning. He juxtaposes warm ochres and golden yellows on the sunlit façade against cooler greens and blues in the meadow and tree canopy. The grass is depicted through layers of pale lime, jade, and emerald, punctuated by strokes of lemon to capture the glint of sunlight. Shadows beneath the foliage register as deep teal and violet, lending depth and structure. The lake’s surface shimmers with silvery grays and muted blues, reflecting the sky’s luminosity without overpowering the scene. By orchestrating these complementary hues, Cucuel achieves a chromatic balance that feels both naturalistic and subtly heightened.

Brushwork and Textural Qualities

Diverging from smooth academic finishes, Cucuel’s touch is characteristically impressionistic. In the foreground, short, dashed strokes impart the tactile softness of grass, while thicker impasto on the tree trunk conveys the roughness of bark. Foliage is sketched with overlapping dabs of green and gold, capturing the play of light among leaves. The plaster walls of the cottage are rendered with broader, more deliberate strokes, yet still show the bristle marks of the brush. This rhythmic alternation of fine and bold gestures enlivens the surface, inviting the viewer’s eye to dance across the canvas and to reconstruct forms from an array of color notes.

Architectural Elements and Domesticity

Cucuel pays careful attention to the vernacular details of his dwelling. The wooden shutters, slightly ajar, reveal a glimpse of shadowed interior space, while the stone threshold and steps anchor the building to the earth. The low-pitched roof, tiled with reddish-brown clay, extends just beyond the walls, casting a cool shadow that complements the sunlit façade. Ivy tendrils and flowering vines climb organically over the masonry, suggesting neglect of rigid boundaries in favor of natural integration. These elements collectively convey a sense of lived-in comfort, underscoring the painting’s theme of domestic refuge.

Flora, Fauna, and Organic Motifs

Though no animals appear, the painting teems with botanical life. The broad-leafed tree dominates the scene, its heavy canopy filtering light and creating dappled patterns on the ground. Beneath it, scattered undergrowth hints at wild grasses and low shrubs illuminated by sunlight. The riot of roses climbing the cottage wall introduces a burst of color and suggests seasonal abundance. Even the path—lightly trodden and edged by blades of grass—speaks to the land’s organic rhythms. Through these vegetative motifs, Cucuel affirms nature’s omnipresence and its capacity to envelop human constructions in vibrant growth.

The Pathway as Visual and Symbolic Device

A seemingly innocuous dirt path curves from the bottom edge of the canvas toward the house and beyond, where it disappears into shadow. Visually, it serves as a leading line, drawing the eye through foreground, middle ground, and into the painting’s core. Symbolically, it can be read as an invitation—an entry point to the artist’s world and a metaphor for the creative journey. The path’s gentle curve suggests both guidance and openness to discovery, acknowledging that the route to inspiration is rarely straight but often enriched by detours and shaded retreats.

Water, Reflection, and the Lake’s Presence

Though the lake occupies only a slender band at the left, its presence is pivotal. Cucuel renders the water with smooth, horizontal strokes that contrast with the vertical thrust of the tree and the angular geometry of the house. The lake’s silvery surface mirrors the sky’s luminosity, anchoring the composition in atmospheric depth. Its reflective quality evokes themes of introspection and tranquility, suggesting that the artist’s sanctuary extends beyond the physical dwelling into realms of contemplation. Even as we remain on land, our gaze is drawn to the shimmering threshold between earth and sky.

Scale, Perspective, and Viewer Engagement

Cucuel positions the observer at a respectful distance—neither too close to feel intrusive, nor too far to lose intimacy. The low vantage point, slightly below eye level, accentuates the height of the tree and the solidity of the house. The compressed depth, achieved through a low horizon, fosters a sense of enclosure, akin to stepping into a private garden. This spatial arrangement heightens viewer engagement: we feel invited to traverse the path, to pause in the shade, to peer through the open window. The painting thus becomes an experiential space, rather than a mere visual representation.

Interplay of Structure and Nature

One of the painting’s most compelling attributes is the seamless fusion of human architecture and surrounding flora. The sturdy tree trunk appears to support the dwelling’s corner, its branches hovering protectively above. Conversely, the vines that snake up the façade echo the tree’s organic shapes, blurring the boundary between built form and botanical organism. This reciprocity suggests a mutual dependence: the house gains warmth and character from its green cloak, while the vegetation finds purpose in adorning human creation. Through this interpenetration, Cucuel expresses a harmonious vision of human habitation within the living landscape.

Symbolism and Psychological Dimensions

Beneath its serene surface, the painting resonates with symbolic undercurrents. The solitary tree may represent the artist himself—rooted, stoic, and reaching skyward. The open window, a portal into hidden spaces, hints at inner life and imaginative potential. The path signifies a creative odyssey, winding yet resolute. The distant hills and shimmering water evoke aspirational horizons, reminding us of the infinite possibilities beyond the immediate setting. Collectively, these motifs convey a narrative of personal renewal, artistic exploration, and psychological anchoring in postwar uncertainty.

Stylistic Influences and Comparative Contexts

While Cucuel’s technique aligns with the Impressionist canon—broken color, emphasis on light effects—he tempers his palette with a structural discipline inherited from the Barbizon painters. Unlike the strict pointillism of Neo-Impressionism, he applies color in more fluid, varied strokes. Comparisons can also be drawn to the American Luminists of the mid‑19th century, who valued tranquil waters and atmospheric depth. Cucuel’s transatlantic education allowed him to merge these diverse influences into a unique idiom that privileges both chromatic richness and compositional coherence.

Technical Aspects: Materials and Execution

Executed in oil on canvas, the work displays Cucuel’s mastery of medium. He likely prepared the ground with a light-toned primer, allowing luminous underlayers to permeate the surface. His brush selection varies from stiff bristles for impastoed bark to softer filaments for delicate foliage. The impasto areas—particularly on the tree trunk and flower clusters—retain tangible depth, while thinner, scumbled passages in the sky and water achieve a sense of airy lightness. The paint’s quality and the artist’s controlled application have preserved both color vitality and physical texture over the past century.

Provenance, Exhibition History, and Reception

“The Artist’s House on Lake Starnberg” first appeared in a Munich Secession exhibition in 1921, where critics praised its “quiet lyricism” and “vibrant handling of light.” It subsequently entered a prominent private collection in Bavaria before crossing to the United States in the late 1930s. During mid‑century retrospectives of American expatriate painters, Cucuel’s work received renewed attention for its transnational character. Today, the painting is often included in surveys of interwar plein air painting and appears in catalogs exploring the migration of Impressionist techniques beyond France.

Contemporary Resonance and Legacy

In the context of modern environmental awareness and the resurgence of interest in domestic retreats, Cucuel’s vision of a home in harmony with nature feels prescient. His emphasis on sustainable coexistence between architecture and landscape echoes current ecological design principles. Moreover, the painting’s intimate scale and humanized perspective anticipate contemporary artistic concerns with place‑making and site specificity. Collectors and curators today regard this work as both a historical document of post‑World War I renewal and as an enduring testament to the restorative power of simple, natural settings.

Conclusion

Edward Cucuel’s “The Artist’s House on Lake Starnberg” stands as a luminous testament to an artist’s reconciliation with nature in the wake of conflict. Through its masterful composition, vibrant palette, and textured brushwork, the painting conveys a deeply felt sense of domestic refuge and creative renewal. The humble cottage, dwarfed yet embraced by the majestic tree and reflected in the tranquil lake, embodies a harmonious union between human presence and the living landscape. A century on, this work continues to captivate viewers with its serene beauty and its eloquent invitation to dwell, even momentarily, in a world where art and nature converge in timeless accord.