Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

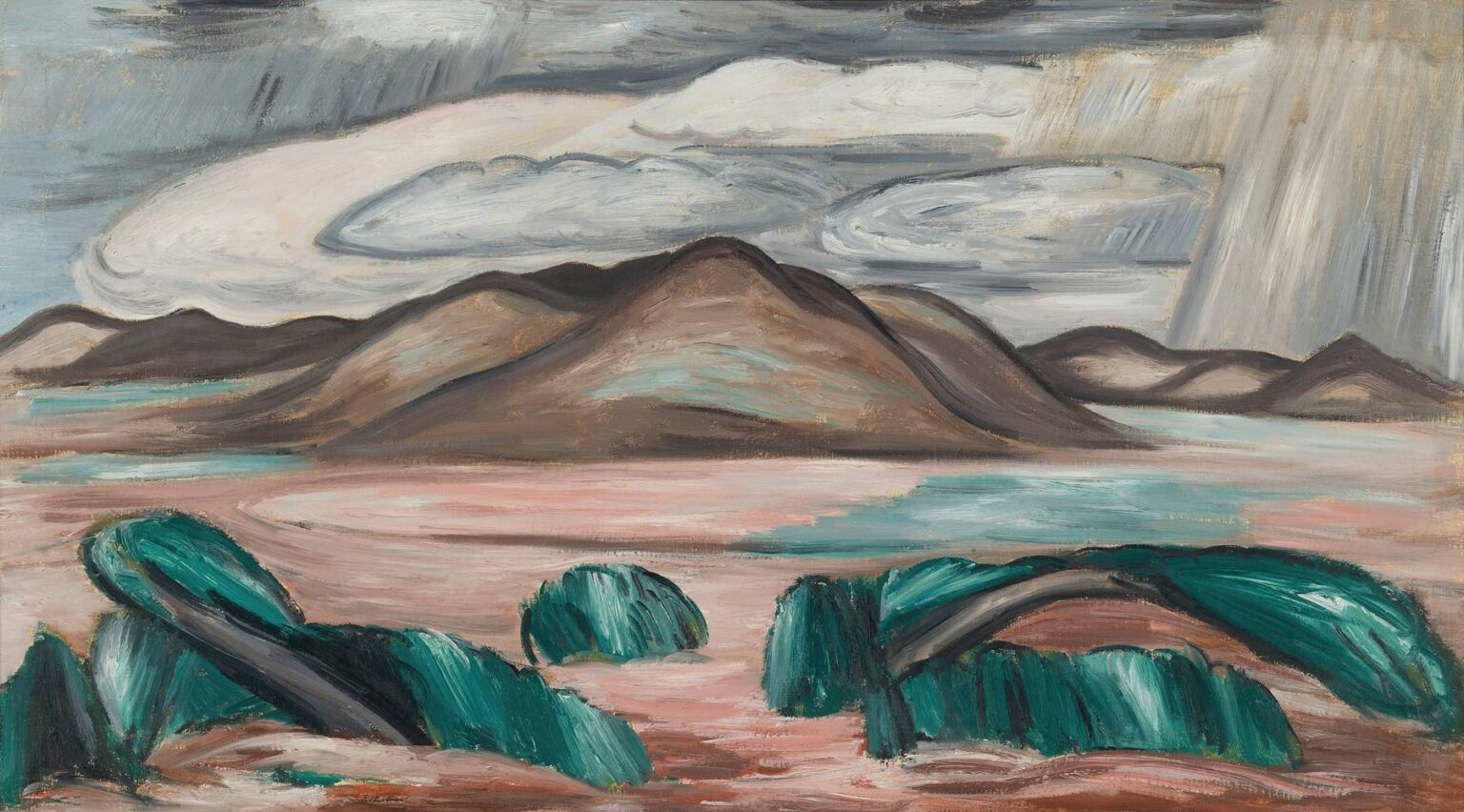

Marsden Hartley’s New Mexico Recollection No. 8 (1923) is a storm-charged remembrance distilled into paint, an image in which memory, geography, and modernist form converge. Rather than reporting a scene plein air, Hartley reconstitutes the Southwest from distance and time, summoning a desert basin, undulating mountain ridge, whipped shrubs and a sky sluiced with rain as if they were motifs in a personal hymn. The canvas breathes with recollection: edges soften, colors shift toward the symbolic, and structures are simplified into rhythmic bands. What results is neither a literal transcript of the New Mexican plateau nor a purely abstract design, but a felt topography where emotion, weather, and form are indivisible.

The Itinerary Of Memory: Why “Recollection” Matters

Hartley first encountered the American Southwest in the late 1910s, when grief and dislocation drove him to seek new spiritual coordinates. By 1923 he was back in the Northeast, yet the desert remained lodged in his imagination. Labeling this work a “recollection” reveals a crucial stance: the painting is an act of remembering, not re-seeing. Memory edits, intensifies, exaggerates. The low mountains take on a sculpted inevitability. The sky turns operatic, layered with elongated cloud coils and vertical sheets of rain. The foreground shrubs bend like calligraphic marks. Hartley leans into this interior process, allowing mnemonic compression to generate formal clarity. In doing so he acknowledges that authenticity in art may arise not from optical accuracy but from faithful translation of experience’s afterglow.

Compositional Architecture And The Stage Of The Basin

The painting is built on three horizontal registers. The lowest is the foreground plain, a rose and ochre field dotted with teal-green shrubs that arc and bow as if buffeted by gusts. The middle register is the long, reclining mountain ridge, its apex slightly left of center, giving the eye a fulcrum around which to circulate. The upper register is the sky, divided into rolling cloud bands and a dramatic diagonal veil of rain at the right. Hartley hinges these zones together through echoing curves: the shrubs’ backs repeat the ridge’s contour, and the ridge’s swell reflects the cloud’s cyclonic loop. This mirroring unifies earth and atmosphere, suggesting that the basin is an arena where forces above and below enact the same choreography.

Spatial Rhythm And The Pulse Of Line

Depth is suggested, but Hartley refuses traditional perspective vanishing points. Space is flattened into adjacent belts whose boundaries are articulated by soft but insistent lines. The ridge’s contour is drawn as a dark, caramel-brown stroke; the shrubs are outlined in near-black against turquoise interiors; cloud edges are limned with gray. These lines beat like a metronome across the surface, guiding the eye laterally as much as into the picture. The sky’s rain sheet—angled, streaky, and translucent—adds a counter-rhythm, a vertical tremolo against the horizontal swell. Space, then, is rhythmic rather than geometric, paced like breath or verse, and the viewer’s gaze follows the cadences Hartley lays down.

Palette Of Dust, Aqua, And Storm Light

Color here is restrained yet idiosyncratic. The ground glows with muted pinks, terra-cotta, and peach tones that intimate desert clay seen through thin air. The hills are modeled in taupe and brown, but Hartley cools their slopes with mint and aqua, as if mineral deposits or reflected sky imparted an otherworldly cast. The shrubs explode in saturated teal and emerald, their intensity heightened by the surrounding neutrals. The sky is a symphony of grays, from dove to charcoal, broken by milky whites that carry the bulk of the cloud masses. Where rain slants, he drags pale grays vertically, letting the underpainting flicker through to mimic veils of precipitation. The result is a palette that feels both remembered and heightened, faithful to desert austerity while tuned to emotional resonance.

Brushwork, Impasto, And The Weathered Surface

Hartley’s handling is muscular yet measured. He stirs paint into broad, creamy strokes for the clouds, carving their ovoid forms with a loaded brush that leaves ridges catching ambient light. He drags thinner, more transparent layers for the rain sheet, allowing streaks to accrue in parallel. The mountain ridge is modeled with scrapes and short sweeps, suggesting striations of rock. In the shrubs, he deploys swift, arcing strokes, piling viridian and teal so thickly that the vegetation seems to bristle from the canvas. Throughout, the ground’s initial warm wash peeks through abrasions, evoking the erosive forces that shape desert landforms. The tactile surface becomes a record of process, equating the painter’s gestures with the meteorological gestures playing out in the scene.

Weather As Drama And Metaphor

The painting’s meteorology is not incidental. Clouds coil like amphitheater balconies, and rain descends in a single dramatic curtain, catching the viewer mid-event. Weather is the protagonist, announcing both threat and renewal. In New Mexico, rain is rare, transformative; here it slices the right side, implying a localized downpour that never quite reaches the foreground. As metaphor, that diagonal torrent can read as memory itself—partial, selective, illuminating one zone while leaving others parched. The bending shrubs mirror human responses to unseen pressure, bowing but unbroken. Hartley thus converts atmospheric phenomena into psychological states: tension before release, resilience under strain, the ache of distance bridged by sudden lucidity.

Symbolic Undercurrents And The Spiritual Landscape

Hartley often embedded spiritual aspirations in landscape forms. The mountain ridge, centered and symmetrical, evokes an altar or a sleeping giant, a presence the painting gathers around. The looping cloud resembles an aureole, haloing the summit. The rain shaft, rectilinear against organic forms, could be a column of light or a veil, a liminal zone between realms. Shrubs stand as witnesses or congregants, their repeated shapes like kneeling figures. Without explicit iconography, Hartley constructs a devotional scene in which nature is the temple and weather the liturgy. The desert becomes a place of passage where the finite meets the infinite, the personal intersects with the elemental.

Between Regionalism And International Modernism

Painted in New York yet drawn from Southwestern recollection, the canvas threads American regional specificity through a European modernist loom. The simplification of forms, insistence on contour, and orchestration of broad color zones owe debts to Cézanne’s structural landscapes and German Expressionist rhythm. Yet the subject—arroyos, mesas, desert flora, storm cells—is distinctly American West. Unlike some contemporaries who romanticized the Southwest as exotic, Hartley processes it through an inner filter, neither ethnographic nor touristic. He gives America’s arid heartland a modernist idiom, proving that abstraction and memory can serve regional truth without cliché.

Serial Thinking And The Discipline Of Repetition

“Recollection No. 8” implies at least seven predecessors. Hartley treated memory like theme and variation, returning to motifs—the bowed shrubs, coiled cloud, central ridge—to test new balances. Each recollection is a proposition: how pink can the earth go before it loses groundness? How far can rain tilt without slicing the composition? How many shrubs are needed to set a rhythm? This serial mindset is musical, scientific, and spiritual at once. It demonstrates discipline beneath spontaneity, showing Hartley as a thinker who refines intuition across iterations. The number eight, in its infinity-loop suggestion, slyly nods to the endlessness of recall.

Emotional Timbre: Distance, Desire, And Calm After Storm

The painting’s emotional register is complex. There is yearning in the very act of recollection, a desire to reinhabit light and air left behind. There is tension in the storm, the bowed shrubs, the gray canopy. Yet there is also poise: the ridge stands firm, the composition holds, the colors hum rather than scream. Hartley balances ache with acceptance. The memory hurts enough to matter, but it is held gently enough to cherish. In that balance, the painting becomes an image of emotional maturity: the artist does not deny loss or distance; he shapes them into a form that can sustain looking.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

New Mexico Recollection No. 8 deepens Hartley’s reputation as a mediator between inner life and outer land. Contemporary artists who revisit place through memory—Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s imagined figures, Peter Doig’s dreamlike terrains—echo this strategy of recollected construction. Environmental concerns also sharpen the painting’s relevance: the storm’s localized fall can read as drought-era spectacle, the fragile shrubs as ecological sentinels. Museums now position Hartley’s Southwestern works alongside Indigenous and Latinx artists to reframe narratives of the region. Within that dialogue, this canvas testifies to a modernist’s sincere if partial vision, one that acknowledges the land’s force without claiming possession.

Conclusion

Marsden Hartley’s New Mexico Recollection No. 8 is an ode to place processed through time. Its coiling clouds, slanting rain, crouched shrubs, and steadfast ridge are less a map than a mantra, repeated until distilled. In compressing the desert into rhythmic bands and tuned hues, Hartley honors both the land’s grandeur and the mind’s alchemy. The painting invites us to trust memory’s capacity to reveal essence, to see weather as emotion’s analogue, and to accept that modern form can carry spiritual weight. Decades after its making, it still feels like a storm on the horizon of consciousness, gathering, breaking, and clearing space for clarity.