Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

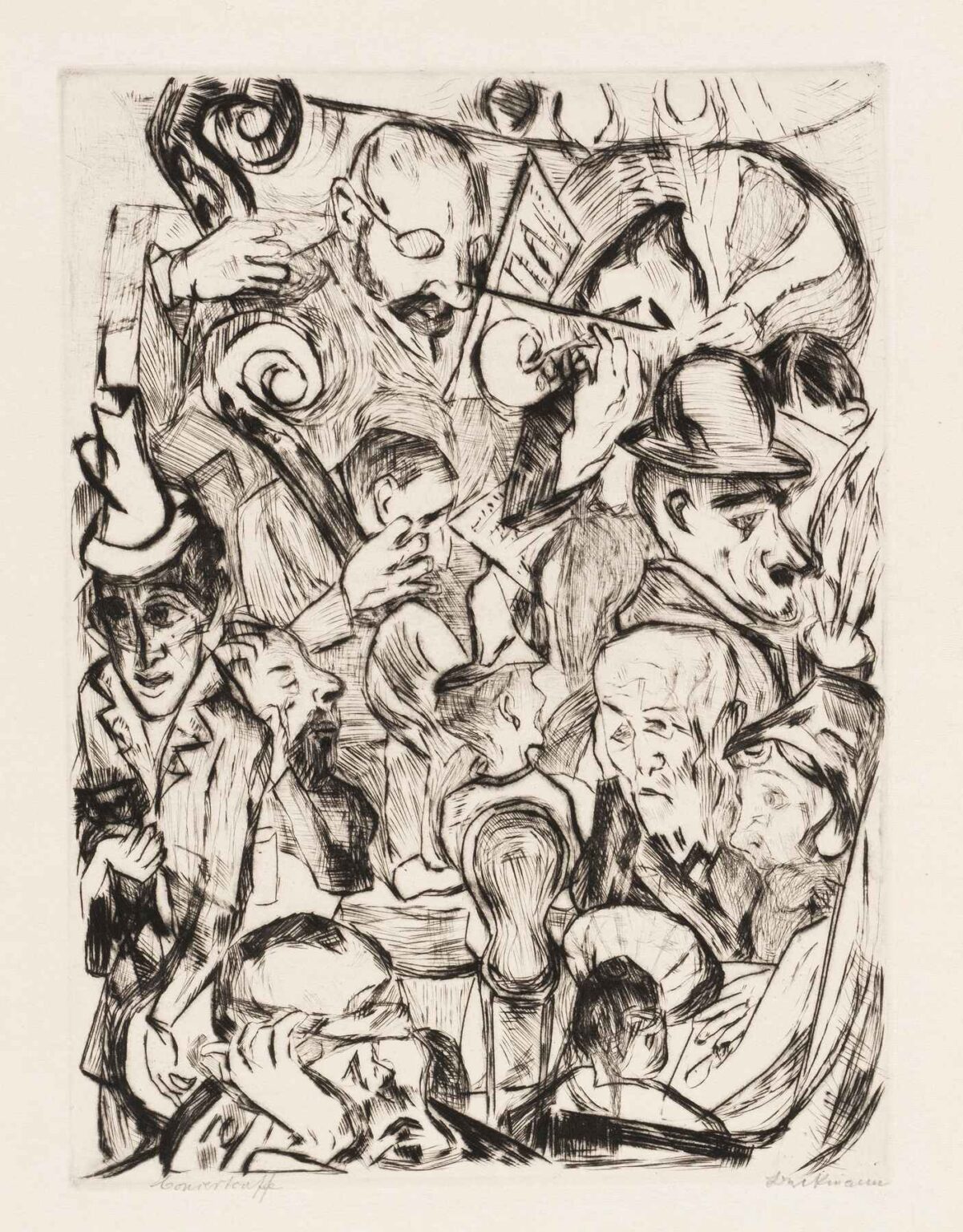

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl. 13 stands among the most compelling works of his early etching cycle, created during the upheaval of World War I (circa 1914–1918). Far from a conventional portrait, this plate assembles a crowded tableau of visages, hands, and musical motifs into a tightly compressed composition pulsing with narrative tension. Executed when Beckmann was transitioning from academic training into his own Expressionist idiom, Pl. 13 reveals the artist’s fascination with the human face as a vessel of emotion, social role, and inner turmoil. Working on copper with a hard ground and drypoint burr, Beckmann transforms line into an instrument of dramatic storytelling. This analysis will examine the historical context of the plate, Beckmann’s technical innovations, the composition’s dynamic spatial structure, the symbolic resonance of faces and masks, and the work’s enduring significance.

Historical Context: World War I and Artistic Turmoil

The years 1914–1918 reshaped Europe in unprecedented ways. As nations mobilized for total war, artists confronted the horrors of industrialized conflict. Max Beckmann enlisted briefly and served on the Western Front before illness repatriated him to Berlin. The trauma of trench conditions, mechanized slaughter, and social disintegration left an indelible mark on his psyche and practice. Disillusioned with prewar academic conventions, he turned to printmaking as a medium of immediacy and moral testimony. Rather than depict battle scenes, Beckmann focused on individuals’ expressions—faces that bore the weight of collective anxiety and fractured identity. Gesichter Pl. 13 emerges from this context, a microcosm of wartime experience condensed into a single stage‑like setting.

Beckmann’s Transition to Printmaking

Before the war, Beckmann had trained at the Weimar and Frankfurt schools, mastering painting and drawing. Yet it was etching—an intaglio process involving needle, acid, and copper plate—that most fully captured his need for urgency and directness. In the cramped quarters of wartime Berlin, he found in prints the ability to sketch ideas swiftly, reproduce them, and distribute them among peers. The Gesichter series, initiated around 1916, became a locus for his early explorations of Expressionist distortion, Cubist fragmentation, and a new graphic lexicon of line. With Pl. 13, Beckmann honed these innovations, merging painterly shading with incisive cross‑hatching and dramatic negative space.

Technical Mastery: Line, Burr, and Acid Bite

In Gesichter Pl. 13, Beckmann demonstrates control over every facet of intaglio. He began with a copper plate coated in a hard ground, inscribing bold contours of faces and instruments with confident, curling strokes. Deep acid bites created the velvety blacks in recesses—beneath hats, inside collars, behind scroll‑like cello necks. In contrast, single‑bite exposures produced finer cross‑hatches to model cheekbones, hands, and hair. Beckmann supplemented these etched lines with drypoint burr, rolling a soft halo around key forms like the curve of an ear or the tip of a mask. The interplay of etched darkness, burr‑driven glow, and unetched paper ground yields a rich tonal spectrum reminiscent of chiaroscuro painting, yet uniquely intaglio in texture.

Composition: A Fractured Ensemble

Unlike singular profile studies in earlier plates, Pl. 13 embraces a theatrical ensemble. A reclining musician anchors the lower left, head bowed and eyes closed as though in weary reverie. Center stage, a bearded cellist peers at sheet music, glasses balancing precariously. To his right, the neck and scroll of a violin loom large, intersecting the bowed head of another performer. At left, a pointed‑hat figure resembles a theatrical clown or jester, his half‑smile tinged with unease. The upper corners carry fragmented hands—one gripping a double‑bass scroll, another gesturing at unseen ears. Beckmann compresses these elements into a shallow pictorial space, displacing rules of perspective to heighten psychological intensity.

Faces as Psychological Masks

Each face in Gesichter Pl. 13 functions as a psychological mask, revealing and concealing in equal measure. The pointed‑hat character’s grin suggests gallows humor, the bearded cellist’s furrowed brows convey concentration or inner dread, while the reclining musician’s closed eyes evoke exhaustion or escape. These masks gesture toward the performative demands placed on individuals in wartime—soldiers who must hide fear, civilians who must feign normalcy. Beckmann’s etched lines carve each visage with a blend of realism and distortion: eyes tilt at odd angles, cheeks slump under unseen weight, and features sometimes merge with surrounding drapery. The result is a kaleidoscopic portrait of collective psyche under duress.

Musical Instruments as Narrative Agents

Music recurs throughout Beckmann’s work as a symbol of ritual, community, and transcendence. In Pl. 13, the cello, violin, and double bass are not mere background props but participants in the drama. Their exaggerated scrolls arch like question marks, their strings etched with agitation. The sheet music, sketched with sharp diagonal strokes, becomes a relic of order amid chaos—an emblem of harmony under threat. Beckmann’s choice to depict musicians allows him to explore group dynamics: four or more individuals united by shared purpose yet each bearing unique burdens, much like societies at war.

Spatial Dynamics and Modernist Fragmentation

Beckmann disrupts classical perspective to achieve a modernist fragmentation of space. Faces and instruments occupy multiple planes: the cello scroll juts forward, the masked figure recedes behind drapery, the sheet music tilts diagonally, while the reclining musician’s head overlaps another’s shoulder. This collage‑like arrangement echoes Cubist experiments with simultaneity, presenting different viewpoints within one frame. Spatial compression and overlapping forms create claustrophobia, mirroring the psychological intensity of wartime solidarity and constraint. Viewers must actively navigate the etching’s visual labyrinth, much as individuals struggled to find coherence in a fractured world.

Light, Shadow, and Negative Space

Without broad tonal washes, Beckmann builds light and shadow through line density and the careful use of blank paper. Deeply etched areas—under hats, inside collars, on folded hands—anchor the composition with dramatic black. Mid‑tones appear where cross‑hatches are loosely spaced, modeling flesh and fabric. Large unetched zones—around the reclining figure’s torso and the central negative space—provide relief, framing the clustered elements. This contrast evokes spotlighting on a stage, spotlighting each performer while isolating them against darkness. Negative space thus becomes as expressive as ink, symbolizing absence, silence, or the ineffable gap between individuals.

Symbolic Resonance of Gesture

Hands in Beckmann’s etchings often carry potent symbolic weight. In Gesichter Pl. 13, four distinct hand gestures appear: one grips a scroll with muscular tension; another holds sheet music as if shielding a secret; a third reaches upward in a questioning curve; a fourth rests limply upon drapery. Each gesture communicates a narrative fragment—control, protection, inquiry, resignation. By juxtaposing these actions within the crowded scene, Beckmann underscores the human drive to act, to protect, and to question, even amid collective suffering. Hands become extensions of thought and emotion, etched with the same urgency as facial features.

Relation to Beckmann’s Broader Oeuvre

Although Beckmann is renowned for his later, monumental triptychs and Amsterdam exile prints, Gesichter Pl. 13 reveals the early crystallization of his mature style. The plate anticipates themes of performance and ritual found in works like The Actors (1926) and The Night (1918–19). Its fractured perspective and expressive line foreshadow his later graphic experiments in the 1920s and 1930s. As an early entry in the Gesichter cycle, Pl. 13 demonstrates Beckmann’s rapid departure from academic realism toward his singular Expressionist language, consolidating his position as one of the 20th century’s greatest graphic innovators.

Reception and Legacy

During its initial circulation, Gesichter Pl. 13 attracted acclaim among avant‑garde circles for its technical brilliance and psychological depth. Fellow German Expressionists recognized Beckmann’s capacity to fuse moral urgency with formal innovation. Post‑war exhibitions and retrospectives have since enshrined Pl. 13 as a pivotal work in modern printmaking, often featured alongside his paintings to illustrate the continuity of vision across media. Contemporary printmakers cite Beckmann’s fearless line work and narrative layering as inspiration for approaches that address today’s social and political crises.

Conservation and Presentation

Preservation of Gesichter Pl. 13 demands strict environmental control. The thin etching paper is vulnerable to acidity and light; institutions maintain relative humidity around 50 percent and light levels below 50 lux. Framing uses UV‑filtered glazing and acid‑free mats to safeguard the delicate burr and crisp etched lines. When exhibited, the plate is often paired with other Gesichter impressions, allowing viewers to trace thematic and technical evolutions within the series. Detailed wall labels elucidate the wartime context, Beckmann’s etching techniques, and the symbolic interplay of faces, hands, and instruments.

Contemporary Relevance

Nearly a century after its creation, Gesichter Pl. 13 resonates in an age marked by conflict, displacement, and collective anxiety. Its portrayal of artists and performers huddled in close quarters speaks to the essential role of creative community in surviving trauma. The fragmentation of perspective parallels today’s fractured social landscapes, while the expressive line work inspires graphic artists to explore emotional truth. Scholars continue to study Pl. 13 for its insights into Expressionist aesthetics, intaglio mastery, and the moral imperative of art as witness.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Gesichter Pl. 13 (1914–1918) remains a landmark of modern printmaking. Through masterful etching technique, dynamic composition, and rich symbolism, Beckmann transforms a crowded ensemble of faces, hands, and musical scrolls into a profound allegory of wartime solidarity, creative defiance, and the multifaceted human spirit. As part of his early Gesichter series, the plate marks a turning point in Beckmann’s career—a decisive move toward expressive distortion, narrative complexity, and moral engagement. Today, Pl. 13 endures as a testament to art’s power to confront suffering, forge community, and articulate the inexpressible.