Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

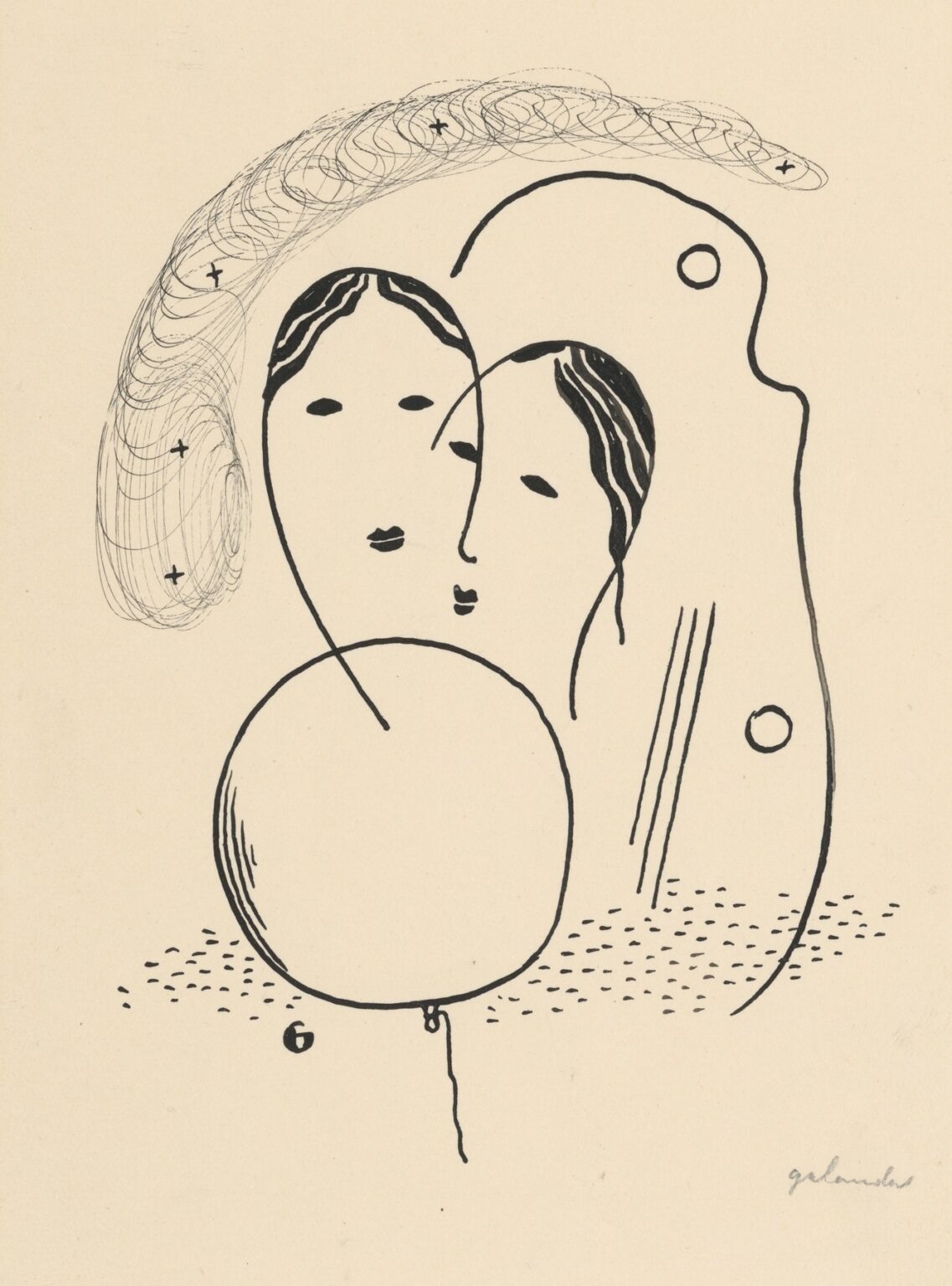

Mikuláš Galanda’s Ball (1930) marks a pivotal moment in the artist’s evolution from a painter steeped in Cubist and Fauvist influences to a master of lyrical abstraction. At first glance, the drawing’s simplicity—a lone, floating circle tethered by a delicate string, bisected by the overlapping, mask‑like faces of two intertwined figures, all crowned by a nebulous arc of spiraling lines—belies its conceptual richness. Executed in black ink on cream paper, Ball exemplifies Galanda’s fascination with the interplay of figurative suggestion and pure form. Over the course of this analysis, we will explore the historical context that shaped Galanda’s practice, dissect the work’s compositional strategies, interrogate its economy of line and symbolic resonance, and reflect on its legacy within the broader trajectory of Central European modernism.

Historical and Artistic Context

In the interwar years, Czechoslovakia emerged as a vibrant center of avant‑garde art, grappling simultaneously with the liberating impulses of post‑World War I optimism and the anxieties of political upheaval. Born in 1895 in the Slovak town of Pezinok, Galanda studied in Budapest and Prague during the height of Cubism’s radical deconstruction of form and Fauvism’s bold chromatic experiments. By the late 1920s, he co‑founded the Bratislava based group Vierka and later the influential Devětsil, aligning himself with artists committed to forging a national modernism that both conversed with Parisian trends and resonated with local cultural traditions. Ball—created in 1930, the same year his celebrated woodcut series Golem appeared—reflects Galanda’s maturing vision: he moves beyond the vibrant color and fractured planes of his earlier work to an economy of black line and open space, evoking emotional depth through minimal means.

Compositional Architecture

At the heart of Ball lies a large, seemingly weightless circle, its contour rendered with a single confident stroke. The circle occupies the lower central quadrant of the sheet, suspended above a field of stippled dots that suggest either the granular surface of ground or the ephemeral shimmer of air. Beneath this orb, a thin line descends, resembling a string or tether, anchoring the floating form to an unseen point beyond the page’s margin. Behind and within the circle, two stylized profiles emerge: their oval heads overlap, sharing a single, continuous outline for their faces and hair. The left profile faces the viewer, its simple ovoid eyes and delicately rendered lips conveying a serene neutrality; the right profile, turned slightly away, is defined by a bold line that curves from brow to chin, suggesting motion or the fleeting nature of identity.

Above these intertwined masks, Galanda arches a cloud‑like mass of looping lines, drawn with swift, swirling motion. Within this halo, small crosses punctuate the turbulence, evoking stars in a night sky or symbolic gestures of transcendence. To the right, a single, free‑standing line curves upward, punctuated by two short parallel strokes and a small circle—motifs that resonate with ancient script or musical notation. The emptiness of the cream paper between these elements—masses of reserved space—imbues the composition with an airy openness, inviting viewers to navigate between figure and ground, form and void.

Economy of Line and the Poetics of Simplicity

One of Ball’s most striking qualities is its radical economy of line. Galanda eschews shading, cross‑hatching, or dense textures in favor of pure, gestural strokes. Each line is charged with intent: the circle’s unbroken curve conveys unity and perfection; the string’s taut descent hints at connection and constraint; the profiles’ shared contour underscores relationality and the porous boundaries of self; the swirling halo above conjures the flux of thought or emotion. By limiting his visual vocabulary to black ink on pale paper, Galanda makes every mark count. The viewer’s eye is guided effortlessly from one form to the next, tracing the relationships implicit in the composition’s spatial choreography. This reductionist approach aligns Ball with the broader modernist quest for abstraction—yet Galanda retains a residue of figuration that grounds the work in human presence.

Symbolic Resonances: The Ball as Archetype

The eponymous ball, simple in form yet laden with cultural associations, stands at the nexus of Galanda’s symbolic inquiry. As a geometric archetype, the circle represents unity, completeness, and cyclical renewal—motifs echoed in philosophical and religious traditions worldwide. In the context of Ball, the floating orb may signify the psyche, a purified soul unencumbered by gravity, or the driving force of creative imagination. Its tether to the margin suggests that even the most sublime ideals remain bound to earthly origins or social moorings. Overlapping with the two profiles, the circle becomes an arena of relational dynamics: perhaps the shared dreamspace of two souls, the union of masculine and feminine principles, or the inseparable meeting of self and other. Through this polyvalent signifier, Galanda invites multiple readings, each attuned to the viewer’s own psychological and cultural horizon.

Interplay of Figure and Abstraction

While the circle and tether verge on pure abstraction, the stylized profiles anchor Ball in the domain of figuration. Yet these faces are themselves abstracted: reduced to ovals, they lack individualizing features such as pupils, noses, or ears. Instead, hair is hinted at by parallel strokes; lips are rendered as delicate curves; eyes appear as elongated ovals. This selective depiction evokes a universal mask rather than a portrait of a specific individual. The result is a liminal space where abstraction and representation intersect: viewers recognize human presence without being drawn into a particular narrative. This deliberate ambiguity resonates with modernist explorations of identity—wherein the self is not a fixed essence but a fluid interplay of forms and impressions.

Spatial Ambiguity and Psychological Depth

Galanda’s handling of space in Ball is deliberately ambiguous. There is no horizon line, no perspective grid, no clear indication of foreground or background beyond the subtle stippling beneath the circle. The profiles and halo seem to inhabit an indeterminate realm, afloat between material world and dreamscape. This spatial openness mirrors the psychological depth of the work: rather than depicting a scene, Galanda suggests a state of mind or a moment of introspection. The viewer is invited to project their own emotional topography onto the blank spaces, filling in the gaps with personal associations. In this way, Ball becomes a mirror for the inner life, a visual counterpart to meditation or free‑association drawing practices.

The Halo and Celestial Allusions

The semicircular halo of swirling lines and crosses above the profiles adds a cosmic dimension to Ball. Its gestural loops evoke circling thoughts, shifting emotions, or the stellar sphere itself. The tiny crosses dispersed within the halo may recall stars, signifying navigation, hope, or the transcendent. Alternatively, they might function as symbolic markers of faith or suffering, referencing Christian iconography without explicitly depicting religious figures. The halo hovers above the human forms, suggesting an interplay between earthly identity and celestial inspiration. In combining dynamic, swiftly rendered strokes with the static stability of the circle and profiles, Galanda captures the tension between change and constancy, the ephemeral and the eternal.

Calligraphic Echoes and Musical Metaphor

To the right of the profiles, Galanda introduces a set of tattoo‑like motifs: a thin, curved line punctuated by three short parallel strokes and a small, isolated circle. These marks resonate with the language of calligraphy or musical notation—suggesting that Ball may be read not only visually but rhythmically. The curved line evokes a musical phrase, the parallel strokes denote beats or measures, and the final circle functions as a rest or point of return. This implied music enlivens the drawing, adding a temporal dimension: just as a melody unfolds over time, so the eye moves through the composition’s forms in a specific sequence. Such synesthetic references underscore Galanda’s embrace of interdisciplinary modernism, wherein art, music, and literature interweave to produce holistic aesthetic experiences.

Technical Execution and Material Presence

Galanda’s choice of pen and ink on paper emphasizes line precision and immediacy. The ink’s deep black saturation contrasts starkly with the warm, off‑white tone of the paper, creating a high‑impact graphic effect suited to both intimate viewing and reproduction in print. Examination of the strokes reveals Galanda’s confident hand: circular passes overlap seamlessly, forming smooth curves; parallel hatching in the halo area displays controlled variation in line weight; the profiles’ contour lines maintain a consistent flow without hesitation. The paper’s slight texture emerges in places where the ink thins, adding a tactile roughness that anchors the drawing’s ethereal forms in physical reality. This material interplay—between ink’s fluidity and paper’s fibrous resistance—mirrors the conceptual interplay of abstraction and figuration at play in Ball.

Legacy and Influence within Slovak Modernism

Ball occupies an important place within Mikuláš Galanda’s oeuvre and the development of Slovak modern art. In 1930, Galanda was at the forefront of artists striving to articulate a local modernism that could converse with international avant‑garde yet maintain cultural specificity. His graphic works—drawings, prints, book illustrations—were instrumental in disseminating modernist aesthetics throughout Czechoslovakia. Ball, with its universal symbolism and accessible visual language, exemplified his democratic vision for art: distilled to essential elements, it could be reproduced in publications, posters, or exhibition catalogs, reaching a broader audience than large‑scale canvases. Subsequent generations of Slovak artists would look to Galanda’s work for its fearless blending of abstraction, poetic figuration, and cultural resonance.

Conclusion

In Ball (1930), Mikuláš Galanda achieves a remarkable synthesis of formal economy, symbolic depth, and modernist innovation. Through a handful of masterfully executed lines, he conjures a floating sphere, entwined profiles, a celestial halo, and enigmatic calligraphic signs—all set against the silent expanse of paper. The drawing’s compositional clarity, its economy of means, and its multivalent symbolism invite viewers into an open‑ended dialogue about identity, unity, transcendence, and the rhythms of inner life. As a testament to Galanda’s vision, Ball transcends its time and place, offering a timeless emblem of the power of abstraction to evoke the universal dimensions of human experience.